FIRST, praise where praise is due.

FIRST, praise where praise is due.

The special effects in Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith are magnificent, even if there are far too many of them and they never provoke quite the same sense of awe that, say, Peter Jackson was able to summon for The Lord of the Rings.

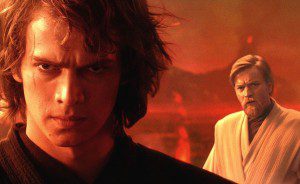

And it is gratifying to see that Ewan McGregor and especially Hayden Christensen, as the Jedi Knights Obi-Wan Kenobi and Anakin Skywalker respectively, have turned in better, more interesting performances in this film than they did in its predecessors. This is no small point, since it is in this film that Anakin turns against Obi-Wan and becomes the evil Darth Vader.

The film’s opening sequence, in which Obi-Wan and Anakin rescue Chancellor Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid) from his Separatist kidnappers — unaware that Palpatine is a sorcerer who has engineered the kidnapping as part of his plan to seize power over the galaxy — is also one of the most exciting, amusing and entertaining chapters in the entire series.

But there isn’t much else to praise here. Natalie Portman, as Anakin’s secret wife Padmé Amidala, has little to do; in the earlier films, she was a fighter, a diplomat, an active political force, but here she has been reduced to a mere pregnant woman. And some scenes are so ripe for parody, they practically satirize themselves; indeed, at the preview screening, I made a point of noting every scene that provoked unintended laughter in the audience.

The earlier prequels — 1999’s The Phantom Menace and 2002’s Attack of the Clones — were surprisingly dull exercises in teenage romance and hokey political conspiracies; obsessed with boring, mundane details like the taxation of trade routes, they had little in common with the grand, mythic archetypes of the original films.

To its credit, Revenge of the Sith finally pushes the story back in a more operatic direction, and it accomplishes this partly because it is about the outright destruction of the Republic’s political system, and can therefore dispense with all that picky, procedural, nuanced wrangling that Palpatine was obliged to hide behind in the earlier films.

Still, old habits die hard, and the film’s characters continue to pay lots of lip service to the need for “diplomacy” and “liberty” and so on. Even Obi-Wan, who expressed his dislike of politicians in the previous film, declares in what should have been one of the film’s most climactic moments that he is fighting on behalf of “democracy”.

This is the first film that Lucas has written and produced since the “war on terror” began, and it is peppered with words and phrases that seem to allude to it.

Interestingly, the opening crawl equivocates between the two sides fighting in the Clone Wars, and tells us simply, “There are heroes on both sides. Evil is everywhere.” Lucas, like so many others, wants to “support our troops” even as he insinuates that the people leading those troops are crooked and inventing phony wars to usurp the political process.

And yet, at a pivotal point in the story, when one Jedi Master is about to take the law into his own hands and assassinate Palpatine, another character insists on the need for due process and says Palpatine should be tried in court — a stalling tactic that gives Palpatine just the leverage he needs to win the day. Some might argue this has parallels to how other, real-world tyrants have used institutions like the United Nations. Is this a clever exercise in dramatic conflict and thematic tension, or is it just another sign of muddled thinking on Lucas’s part?

For all the talk of “democracy”, this Star Wars film is actually less interested than any of the others in the lives of ordinary people, and the romantic dialogue is, of course, laughably bad. Revenge of the Sith proves once again that Lucas has no idea and little interest in how real people relate to one another. This flaw is especially problematic here, since, as Obi-Wan told us in the first film a long time ago, “Vader was seduced by the Dark Side of the Force.” Alas, Lucas is as tin-eared and ham-fisted with spiritual seduction as he is with the romantic kind.

Revenge of the Sith marks the first time Lucas has really shown a person “converting” from one side of the Force to the other, but he never pulls it off. (Some would say Return of the Jedi showed Vader converting back to the good side, but if you watch the film carefully, you will see that Vader never does anything particularly evil there; he has been softened up, between the films, to make his conversion in that final film more palatable to us.)

Anakin, who begins the film a war hero, is convincingly confused in his allegiances — both the Jedi Council and Chancellor Palpatine seed Anakin’s mind with credible doubts about the other — but he never quite decides to take one side against the other. Instead, he is overwhelmed by events out of his control, and nothing quite prepares us to believe that he would be so quick to, say, murder children just because Palpatine tells him to.

Even less satisfying, from a dramatic point of view, whatever negative feelings Anakin has towards the Jedi Order are focused primarily at its Council — yet he has almost no hand whatsoever in its demise. Instead, the Council members are killed by the cloned troopers assigned to them, after Palpatine issues “Order 66” (a nod to the number of the Beast?) and tells the troopers to kill the Jedi. If Anakin’s hatred is supposed to be responsible for his turn to the Dark Side, then it is odd that the main objects of his hate never feel it.

Whatever problems the prequels may have on their own terms, one of their more regrettable aspects is that they have undermined the moral stature of characters we once thought were heroes, yet you suspect Lucas is oblivious to how he has compromised those characters.

For example, Attack of the Clones revealed that the Jedi Order forbade its members to form emotional “attachments” to family members and romantic partners, and it was their dogmatic insistence on this point that drove Anakin to pursue his relationship with Padmé in secret, thus driving a wedge between him and the Jedi Council.

If we treat all six films as one big story, then it seems Jedi Knights like Obi-Wan Kenobi and Yoda (voice of Frank Oz) persisted in this erroneous belief right up until their deaths — and beyond! — and it is only because Anakin’s son Luke Skywalker rebelled against them and expressed his love for his father that Anakin was redeemed in the end.

Similarly, many people of my generation were introduced to relativistic thinking through Obi-Wan’s insistence, in Return of the Jedi, that many of the “truths” we believe depend on our “point of view”. (Obi-Wan made this point when trying to justify his lies about Luke’s father, which raises even more moral problems.) In Revenge of the Sith, this belief is expressed by Palpatine, who persuades Anakin that what is good or evil depends on one’s “point of view”.

So if you were to watch these films in chronological order, you would hear Obi-Wan expressing a belief, near the end of the story, that had earlier been expressed by the evil Emperor.

Things are muddled even further when Anakin and Obi-Wan have their fateful duel — the duel that leaves Anakin so badly wounded that much of his body is replaced with machinery, requiring him to wear the mask that we have all come to know and fear.

Obi-Wan seems to espouse a form of relativism when he tells Anakin, “Only a Sith deals in absolutes!” But when Anakin declares, “From my point of view, the Jedi are evil,” Obi-Wan replies, “Well, then, you are lost.” Does Obi-Wan mean this absolutely? Or would he concede that Anakin was only “lost” from a certain point of view?

Is Lucas trying to show that Obi-Wan’s contradictory thinking was part of the problem all along? After all, Yoda and Obi-Wan continue to think in absolutes right to the end of the story (“He’s more machine than man, now — twisted and evil”), and to seek Darth Vader’s obliteration, even after Luke has learned that Vader is his father and therefore capable of redemption. Or is Lucas himself the contradictory thinker here?

Another major theme running throughout these films has been the relationship between life and death in the natural, physical world. Several scenes in the earlier films have drawn our attention to the food chain, and the animal struggle for survival therein; this may be most explicit in The Phantom Menace, when Qui-Gon Jinn summons one sea creature to protect his vessel from another creature, and says, “There’s always a bigger fish.”

The significance of that focus for human beings is brought home in Revenge of the Sith, in which Anakin turns to the Dark Side partly because he believes it will give him the power to conquer death.

Anakin is haunted by nightmares that seem to predict Padmé’s death by childbirth, and he is not soothed by Yoda’s assurances that death is a “natural” part of life. Palpatine’s assertion that the Dark Side can give a Sith lord the power to cheat death is a key reason for Anakin’s conversion — and thus, it is ironic when both Palpatine and Anakin are wounded so badly and scarred for life in their battles with the Jedi.

Christians can cautiously agree with aspects of this. “The fear of loss is a path to the Dark Side,” says Yoda, and certainly we believe that we need to be prepared to give up everything — even life itself, if need be — for the sake of the gospel. And the near-deaths of Palpatine and Vader do offer a stirring reminder of the biblical adage that those who would save their life will lose it.

But our faith has never been all that sanguine about death itself. The “immortality” portrayed in these films, in which some spirits linger on after bodies die, is, at best, a pale, ghostly substitute for the Jewish and Christian belief in resurrection.

Scholars and fans will no doubt spend years debating to what degree these prequels were already fleshed out in Lucas’s mind when he created the original films. Lucas himself recently admitted to Entertainment Weekly that about 60 percent of the back-story he invented back in the 1970s takes place in Revenge of the Sith, while the other 40 percent was spread out over the previous two movies, with lots and lots of filler.

But one of the main problems with the prequels is not merely that they are padded, but that they are full of plot elements that don’t agree with the original films. Revenge of the Sith introduces such continuity errors right up until its final scenes, which may leave you wondering just how, exactly, Princess Leia could remember so much about her mother while Luke, who appears to be even stronger in the Force than her, remembers nothing.

George Lucas has spent the past decade wreaking havoc with an entire generation’s collective cultural memory, supposedly on the basis that these films — including the gratuitously altered “special editions” of the original trilogy — represent the story he always had in mind. But this would seem to be a rather dubious claim.

It is too bad Lucas could not let well enough alone. The prequels have robbed the Star Wars universe of much of its mystique; it turns out the years of mystery and speculation around the events that transpired before the original films was much more interesting than the depiction of those events that finally came out.

Let us hope that, now that Revenge of the Sith is out, the Star Wars universe will be left alone for a while.

Internet Movie Database | Movie Review Query Engine

USA: PG-13 | BC: PG | ON: PG

— A version of this review was first published at CanadianChristianity.com.