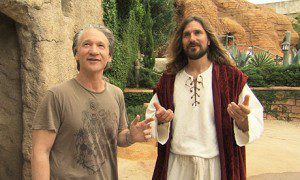

RELIGULOUS is a documentary in which stand-up comedian turned talk-show host Bill Maher tours the world, visiting Jews, Muslims and Christians of various stripes in a bid to prove that religious belief is foolish, childish and basically dangerous.

RELIGULOUS is a documentary in which stand-up comedian turned talk-show host Bill Maher tours the world, visiting Jews, Muslims and Christians of various stripes in a bid to prove that religious belief is foolish, childish and basically dangerous.

Maher’s basic thesis, as the movie’s title suggests, is that “religion” is “ridiculous”, and so, as a professional comedian, he does not merely approach religion as a thoughtful skeptic or agnostic who is not yet convinced of, say, the existence of God. Instead, he “ridicules” the beliefs of the people he meets, often to their faces.

The mocking tone is accentuated by the editing, courtesy of director Larry Charles, a former Seinfeld producer who previously directed the similarly outrageous documentary Borat, as well as the Bob Dylan movie Masked and Anonymous.

The interviews that Maher conducts are routinely interrupted by bits of cheesy stock footage and snippets from other interviews. To tweak the people who appear onscreen, Charles sometimes adds cackling witches and other silly sound effects to the soundtrack, or he uses subtitles that contradict what the interviewees are saying.

So watching this movie is a very different experience from watching one of Maher’s talk shows. On television, Maher invites guests onto his program, and they discuss the issues of the day in real time, without editing, more or less. But in the film, Maher and Charles venture onto other people’s turf with a camera crew, and then they re-mix the footage in a way that gets the cheapest laughs possible.

It would be tempting, at this point, to try to dismiss the film by claiming that it is not funny. But Maher is right about one thing: religion can be a very easy target.

Religious beliefs and practices can be funny. Indeed, religious beliefs and practices can be downright crazy. Evangelical Christians themselves have devoted entire magazines and websites, such as The Wittenburg Door and Ship of Fools, to poking fun at the foibles and outrageous excesses of their fellow believers, and others.

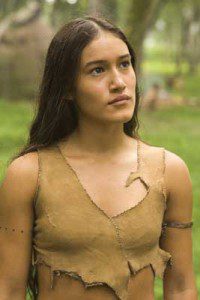

So, in fairness, there are laughs to be had here, cheap though they may be. And on a few occasions — such as when a theme-park Jesus defends the doctrine of the Trinity by saying that water can be solid, liquid or a gas — Maher allows himself to seem surprised, even impressed, by the answers he gets, without going straight for his usual sarcasm.

But too often, Maher takes the easy way out. Armed with probing questions about history, philosophy and theology, he typically aims his barbs at everyday laymen, many of whom have presumably never heard his questions before, rather than speaking to the various experts who deal with these questions for a living.

Once in a while, Maher does speak to a professional academic who happens to be a Christian. But he tends to do this either to enlist the expert’s help in pooh-poohing one of his other, more fundamentalist, interviewees — such as when an evolutionary scientist at the Vatican disagrees with the literalist creationism of Ken Ham — or he tends to steer the conversation to subjects outside the expert’s field of study.

At one point, Maher speaks to Francis Collins, former director of the Human Genome Project and an evangelical Christian, but he needles him with questions about the historicity of the gospels, and whether any of them could be eyewitness accounts — a subject that might be better suited to an historian than a biologist.

More fundamentally, Maher doesn’t seem to understand what religious belief is all about in the first place. He insists that religious people are basically fearful and selfish, that they believe in God only because they don’t want to go to Hell — and admittedly, the fact that several people respond to his disbelief by saying something like “What if you die and you find out you’re wrong?” doesn’t exactly disprove his case.

But he never grapples with the fact that, at the deepest level, people want life to have some sort of meaning, or that they can sense there is, or ought to be, more to this existence than the hedonistic pastimes that Maher is content to settle for.

Nor does he give due credit to the fact that the God most people believe in is not just some “man” who can “hear everybody murmur to him at the same time.” You would think Maher, who has elsewhere expressed an openness to the idea that there is “some force” that can be called God, could be a little more open to the idea of transcendence, or to the idea that this “force” is in touch with its creation, is at least as personal as the people who inhabit it, and can therefore hear their prayers.

After all of his attempts to find humour in his targets, Maher closes the film with a deadly serious rant in which he asserts that there is so much faith-based violence in the world that religion must die if mankind is to survive.

But he never acknowledges the many good things that people have been motivated to do by their faith, from setting up soup kitchens to fighting for civil rights.

What is more, some studies have indicated that people have a tendency to become more superstitious, rather than less, once they ditch traditional religion. And of course, we have the example of officially atheist Soviet Russia. So there is no guarantee that a world without religion would be more rational or less prone to violence.

Maher himself, it turns out, peddles some pretty kooky ideas, such as the thoroughly debunked notion, popularized a few years ago by Tom Harpur’s The Pagan Christ, that the gospels ripped off the details of Jesus’ life story from the ancient Egyptian god Horus.

So it would seem that ridiculous beliefs can be found on both sides of the debate, and that those who call themselves doubters can be pretty credulous when they want to be. Comedian, heal thyself.

— A version of this review first appeared on the website for BC Christian News.