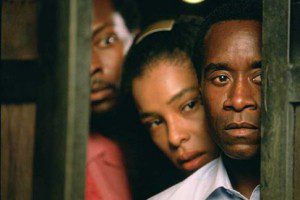

DON CHEADLE is one of those actors who seems to be everywhere these days, popping up in After the Sunset, Ocean’s Twelve, The Assassination of Richard Nixon and so on. But his minor roles in those films pale next to his powerful performance in Hotel Rwanda, the true story of Paul Rusesabagina, a hotel manager who saved over a thousand Hutu and Tutsi lives during the genocidal civil war that afflicted that country ten years ago.

DON CHEADLE is one of those actors who seems to be everywhere these days, popping up in After the Sunset, Ocean’s Twelve, The Assassination of Richard Nixon and so on. But his minor roles in those films pale next to his powerful performance in Hotel Rwanda, the true story of Paul Rusesabagina, a hotel manager who saved over a thousand Hutu and Tutsi lives during the genocidal civil war that afflicted that country ten years ago.

Directed by Terry George (whose scripts for In the Name of the Father and Some Mother’s Son focused on the Irish troubles) from a screenplay he co-wrote with newcomer Keir Pearson, Hotel Rwanda has, predictably, earned comparisons to Schindler’s List. But while there are definite similarities between the two films — Paul bribes officials with money and liquor and uses his connections to save as many lives as he can, just as Oskar Schindler did — there are some differences, too.

First, unlike the philandering Schindler, Paul is a devoted family man; and what’s more, he cannot pretend to rise above the people he is protecting, because he is one of them — indeed, Paul is a Hutu and his wife, Tatiana (Sophie Okonedo), is a Tutsi, and his willingness to stick up for his wife’s kin makes him a traitor in the eyes of some of his fellow Hutus, who regard the Tutsis as mere “cockroaches”.

In addition, to guarantee that the film would be rated PG-13 in the United States, and thus open to all audiences, the filmmakers have eschewed the brutal in-your-face realism of most recent war movies, and are careful to keep the bloody violence and dehumanizing nudity (in a scene where Tutsi women are enslaved as “prostitutes” for the Hutu militias) to a minimum. There are many dead bodies, but the actual killings are kept at a distance.

It may seem like an unfortunate compromise that the visual impact of these atrocities has been toned down in such a manner, but in a way, this actually makes the film more effective. Paul, like some of his relatives and employees, is eager to believe that the rumours of carnage outside the hotel walls are just that — rumours — and the possibility that the violence might spill over into his world, and into his life, keeps things genuinely suspenseful. Plus, the fact that the film focuses on Paul and his family makes us more personally involved in their story.

On one level, the film is a searing indictment of the ineffectiveness of the United Nations and the duplicitousness of those politicians who prevented foreign soldiers from intervening in the Rwandan massacres. In what is almost certainly a nod to the recent animosity between the United States and France, and the mutually hostile expressions of moral superiority thereof, one character specifically pins the blame on both of those countries.

Canada doesn’t come out looking too good, either. Nick Nolte plays Colonel Oliver, the Canuck in charge of the UN forces, and his naive toast to peace near the beginning allows Paul and others to lull themselves into thinking that everything will be okay. When it turns out the Western nations are not actually interested in saving the Africans, but only in evacuating their own people, the colonel is infuriated. And of course, his hands are tied — his soldiers are not allowed to use their guns, and as he puts it, “We’re here as peacekeepers, not peacemakers.”

Through it all, Paul Rusesabagina tries to keep his dignity, and that of his hotel, as well. He does this partly because, if he does not keep up appearances, the officers he bribes will realize that his hotel is little more than a worthless refugee camp. But you suspect he does this also because every bit of order counts in a world that is sliding into chaos.

Cheadle is absolutely magnificent in the role. I could point to a number of scenes that illustrate how passionate, humorous, and deeply felt his performance is, but my favorite is the one where Paul and Tatiana have a quiet moment to themselves, and after they have shared a laugh over an old secret that he has finally told her, he suddenly tells her they may need to be ready to kill their own children, lest a machete-wielding mob get ahold of them. The sudden shift from laughter to desperate tears of denial is bracing, haunting, and utterly believable.

Terry George’s script occasionally pushes our buttons a little too hard, but his film — the release of which coincides with more recent atrocities in Sudan and elsewhere — is a timely reminder that genocide is not merely something that we can look back on decades after the fact, as with so many Holocaust movies, but rather, it is something that confronts us to this day.

Internet Movie Database | Movie Review Query Engine

USA: PG-13 | BC: 14A | ON: 14A

— A version of this review was first published in BC Christian News.