Why is it that when our beliefs, theology, or long held doctrine is called into question, its easy to experience anger as a first response?

Why is it that when our beliefs, theology, or long held doctrine is called into question, its easy to experience anger as a first response?

I recently wrote a couple of articles dealing with the “rapture”, the first being a piece that explains how bad eschatology can detrimentally impact our social ethics, and the latter was a piece that laid out a few of my theological reasons for rejecting doomsday eschatology. While I’m no stranger to hate mail, the issue of the rapture seems to have struck a nerve– so much so, that for the first time ever, I saw the number of likes on the Facebook page actually go down.

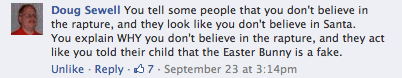

One of the members of the page accurately commented:

The truth of the comment caused me to think about this on a bigger level, especially considering my own history coming out of a black and white religion and embracing the tension of living in the “gray” zone of faith. Back in the day, my first response to any theological question or claim which deviated from the script I had been handed, was anger. It was almost an immediate trigger the moment a question, thought, or idea was thrown out on the table. This anger would quickly tap into an almost instinctive reaction to try to turn the tables on the person asking the question, or making the claim. Winning the debate on legitimate merits was intellectually preferred, but discrediting them always seemed to be a valid, secondary option if I was unable to actually present a “check mate” argument.

Now, as a writer, I find myself frequently receiving e-mails from the old me.

Which, feeds my question: why do we get angry simply because someone holds different theological views than we do?

The answer I think I’ve arrived at, is that we actually don’t— we get scared. Like many other fears, this emotion manifests itself in irrational forms, and the way it plays out simply looks like anger.

But, its not. It’s fear.

When we encounter someone who has, what sounds to be a reasonable and convincing view on a particular theology that challenges one of ours, we get scared. The more our mind tells us that the alternative position sounds good, the more scared we get. The subconscious question then becomes: “If I’m wrong about this, what else am I wrong about?”

And well, that’s a scary position to be in. I get it.

Not only do I get it, I actually lived in that fear 24/7 for nearly my first year of seminary. If faith were a stool with four legs, we all have a particular leg, which if weakened, could make the whole thing topple over– or at least we fear that it would. When something even seemingly small and insignificant (i.e, the “rapture”) encourages us to rethink a previous belief, we opt to live in fear and denial in a subconscious effort to protect all the legs of the stool.

Ironically, when we choose to live in fear in order to protect our faith, the more progressively fragile it becomes. The more conscious we become about our own irrational fear, the more we actually feed that fear– because we start to realize that if minor matters, such as changing our position on eschatology could damage our faith, we didn’t have a very strong faith to begin with.

Ironically, when we choose to live in fear in order to protect our faith, the more progressively fragile it becomes. The more conscious we become about our own irrational fear, the more we actually feed that fear– because we start to realize that if minor matters, such as changing our position on eschatology could damage our faith, we didn’t have a very strong faith to begin with.

And so, the angry beast feeds itself.

Any faith worth having, should be a faith that’s big enough, and strong enough, to handle big and small questions alike.

Thankfully, I’ve come to believe that the faith tradition which seeks to emulate Jesus, actually is big enough and strong enough to handle my questions, doubts, or even changing theology. Now that I’ve come so far in my transition, I no longer respond in fear or anger because as I look back on the process, I see that the stool never fell over– even when I was sure it would.

It’s still there… and perhaps stands a bit stronger.

There is a treatment modality therapists use called “Prolonged Exposure Therapy”, which for many people has been extremely helpful in reducing symptoms of PTSD, phobias, and generalized anxiety. The way it works, is instead of avoiding a particular fear, you force yourself to experience it head on, repeatedly, until you realize the very thing you fear is something that won’t actually harm you. For example, if one had a fear of going to the mall, with prolonged exposure you would actually force yourself to go to the mall, and remain there until the feelings of panic had subsided. If repeated enough, one begins to internalize that going to the mall doesn’t actually harm you, and need not be feared.

However, there is a potential downside: if you were to leave the mall before your feelings of anxiety began to subside, you would actually make the situation worse by rewarding the drive of fight or flight– instead of starving that reaction to the point of realizing that you’re actually completely safe.

I think those of us who respond to theological questions and doubt with fear and anger, would benefit from some prolonged exposure. For me, seminary became my prolonged exposure– after three years deep in the questions, I realized that I was completely safe, and that my faith was intact (even though it looked different). Perhaps for you, it simply means that you give yourself the freedom and permission to spend some time exploring the question you have, but are afraid to admit having. Or, maybe it just means that instead of attacking someone or walking away, you begin asking, “That’s an interesting view. Tell me why you believe that?”

If you give yourself enough time in these questions and discussions, I think you’ll actually be surprised to discover that you’ll come out of it just fine.

Maybe even with a stronger faith, like I did.

And, for those of us who have already navigated this difficult paradigm shift, perhaps we can begin to show a little more grace– realizing that the “others” really aren’t angry and miserable people– they’re just scared.

If we become willing to walk and wrestle in the tension with each other, perhaps we’ll both arrive at the other side with a stronger, more vibrant faith.