Today, the Senate impeachment trial of President Donald J. Trump begins in earnest. As we all continue to hope that the persons who are charged with listening carefully to evidence, then with voting on that evidence after clearly weighing the evidence free from bias and tribal commitments, will actually do so, I am reminded of just how hard it is to think clearly–especially when the stakes are high. And that reminds me of something I wrote about a year ago that seems strangely relevant . . .

I recently read the following observations:

They weren’t such bad fellows. He had mixed with their type all his life: patriotic, conservative, clannish. For them, ______ was like some crude gamekeeper who had mysteriously contrived to take over the running of their family estates: once installed, he had proved an unexpected success, and they had consented to tolerate his occasional bad manners and lapses into violence in return for a quiet life. Now they had discovered they couldn’t get rid of him and they looked as if they were starting to regret it.

No big surprise here—we’ve been hearing a lot about buyer’s and voter’s remorse recently. Later, the author observed another phenomenon that we all have become more and more familiar with. No matter what the person in question said,

People would believe it, because people believed what they wanted to believe—that was ______’s great insight. They no longer had any need to bother themselves with inconvenient truths. He had given them an excuse not to think.

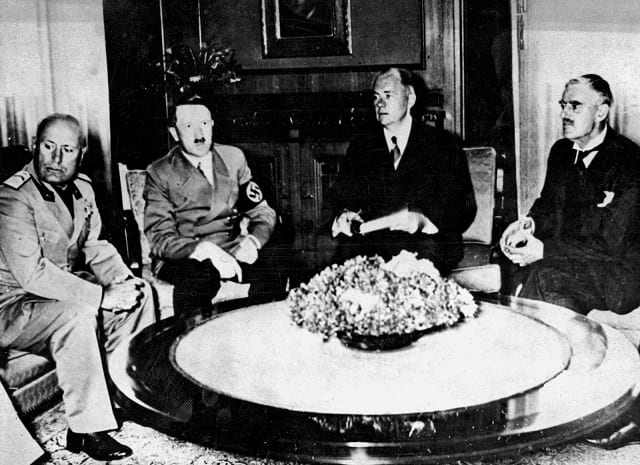

No kidding, I thought. But this was not an article about the Republican Party’s evolving attitudes concerning Donald Trump, nor was the later observation referring to the tendency of Trump’s base to believe everything he says. These passages are from Munich, Robert Harris’ 2017 novel about the ill-fated 1938 Munich Agreement, an agreement between the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Hitler’s Germany that, according to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain established “peace in our time,” only to be shattered in the succeeding days and weeks as Germany invaded Czechoslovakia, then Poland, and World War II began.

These comments are Paul von Hartmann’s—one of the novel’s two main characters—observations about his fellow German mid-level politicians and bureaucrats, upon whom it is dawning, too late as it turns out, that the crude and boorish guy in charge is not only more dangerous than they thought, but also increasingly impossible to get rid of.

In the second passage a few pages later, von Hartmann is noting, with reluctant admiration, the truth of Joseph Goebbels’ insight that people will believe whatever they want to believe, often in the face of contrary evidence. For many of us, the “truth” is not something we discover on the basis of argumentation and evidence-gathering; rather, the “truth” is something that we establish first for all sorts of reasons, then seek to support by cherry-picking favorable evidence while ignoring everything that might count against our assumptions.

I read Munich over Christmas Break, both because I love historical fiction and because I thought it might be an interesting way to finish preparing for the “Grace, Truth, and Freedom in the Nazi Era” colloquium that I am team-teaching this semester. Now about one month into that course, it is clear from our study of real persons involved with and caught up in the rise of Hitler and the Nazis that Paul von Hartmann, although a fictional character, is disturbingly accurate in his observations of German civil servants, bureaucrats, and politicians, as well of millions of German citizens who either embraced the rise of the Nazis, selectively supported it, or chose to look away for an number of reasons.

But as I often tell my students, studying the events of the past needs to be more than a spectator event. Our work in this colloquium has to be more than a semester-long, in-depth tour of the Nazi wing of “The Worst that Humans Can Be” museum. With no prodding from me, my nineteen- and twenty-year-old students are able to see in short order that if one fill in the blanks above with “Donald Trump” in the first quote and “Andrew Breitbart’s” or “Steve Bannon’s” in the second, the passages become directly relevant to now with no loss of meaning. Many American citizens place a lot of faith in the fact that in this country we have many more safety valves and constitutional layers of safety nets than were in place in 1920s and 1930s Germany. But we are experiencing something now so reminiscent of what happened then that we ignore or turn a blind eye to the glaring similarities at our peril.

To be honest, however, I find Goebbel’s insight about the human tendency to believe whatever we want to believe, then find ways to establish it as “truth,” to be more disturbing than any parallels between Adolf and Donald. Thinking is hard, so much so that each of us frequently seeks for a “get out of thinking free” card in various areas of our lives. This card can be a matter of not questioning authority, laziness, chosen ignorance, or any number of other tactics that each of us can become far too skilled with.

In another colloquium I am team-teaching this semester, “Apocalypse,” we just finished our first unit on apocalyptic thinking infused with religious belief. We began with biblical texts such as “Daniel” and “Revelation,” then studied various apocalyptic groups, “cults” if you will, that took these and similar texts seriously and ran with them in ultimately damaging and destructive ways. Jonestown, the Branch Davidians, Heaven’s Gate—each of these groups began, sometimes ended, with people treating their various interpretations of complicated texts and situations with an energy of unwarranted and unearned certainty.

It often seems that people are most likely to excuse themselves from thinking when the stakes are the highest. Attach yourself to a set of beliefs, treat them as if they are certain and immune to change or revision, and you’re good. For example, over the past several weeks on this blog, my essays have frequently explored the blurry boundaries between truth and opinion, faith and intellect, belief and action—all matters in which most of us would be far more comfortable with sharp and clear dividing lines than with shifting and blurry boundaries.

For the very same essay I have been taken to task by evangelical Christians for not respecting the clear and obvious truths of the faith, while being criticized with similar energy and self-righteousness by atheists who cannot believe that anyone with a brain fails to clearly accept the non-existence of God. I am reminded that it is not the content of what we believe that causes us to stop thinking and treat our beliefs as if they are certain. A person can become rigid in their thinking about anything—it’s far easier to embrace an unwarranted certainty than to commit to the far more difficult task of continual revision and updating of what one believes to be true.

I was reminded this week as I prepared for a class on the work of Simone Weil of something she wrote in a letter to a Jesuit priest friend in an attempt to explain why she, on principle, steadfastly refused to become a baptized member of his religion, just as she on principle refused to sign on the dotted line of any doctrinal statement, religious or secular, faith-based or political

It seemed to me certain, and I still think so today, that one can never wrestle enough with God if one does so out of pure regard for the truth. Christ likes us to prefer truth to him because, before being Christ, he is truth. If one turns aside from him to go toward the truth, one will not go far before falling into his arms.

Weil’s larger point, one that goes beyond simply refusing to accept doctrinal limitations on her search for what is greater than us, is simply this: The truth is bigger and more resilient than we think it is. The truth is larger that whatever straitjackets we seek to impose on it. Don’t be afraid to question everything, even one’s own beliefs that seem most foundational and certain. Because the truth is greater than we are. Don’t be afraid.