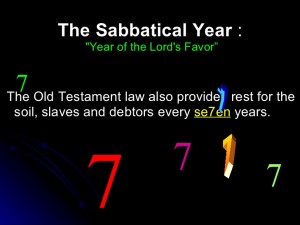

Fall semester classes started last Monday. And I’m on sabbatical, not returning to the classroom until the day after MLK day in January. I’m sure that my colleagues are probably jealous of those colleagues, such as myself, who are on sabbatical—but I don’t feel guilty about that. I felt the same way each of the last six Augusts about my colleagues who were beginning sabbatical. Unfortunately sabbatical only shows up once every seven years—that means that six out of every seven Augusts a professor is going to be overwhelmed by envy.

Explaining sabbatical to non-academics is very difficult; it’s hard enough to explain why teaching is not a part time job when one is in the classroom every day. In my experience, most academics do a lousy job at such explanations. Most non-academics do not know exactly what sabbatical is. But they do know that for a semester or year the person on sabbatical is not going to be in the classroom, which means (obviously) that sabbatical is vacation. When a teacher is not in the classroom, she is not working—right?

No amount of explaining that sabbatical is the time when professors research, write and publish, all of which are requirements for promotion and tenure (another academic thing non-academics don’t get), or of describing the hoops that must be jumped through (proposals, committees, etc.) in order to be approved for tenure matters a whit. What makes you so special to warrant getting several months off every seventh year? Paid, no less? Do you think you work harder than normal people do? Do you live in a rarified atmosphere than normal mortals can only aspire to?

This, of course, is likely to produce an ill-conceived and defensive response from the academic, who then comes off sounding as if she really does think she is special, that he does work harder than anyone else, that the academic does deserve a perk that virtually no one else has access to. But I think we can do better than this, fellow professors. Step one—stop apologizing for having access to something that, in a better world of work and employment, would be the norm rather than the exception.

A few years ago, on one of the NPR shows I listen to when in the car (I forget which one—they all start melding together after a certain time), Netflix’s newly announced policy of a full year’s paid leave to new parent employees was the topic of discussion. “Wow, those wild and crazy companies like Netflix, Google and Microsoft! Unlimited vacation time, no required number of working hours per week, and now this! What will they think of next?” A bit of perspective was then provided by a caller about twenty minutes in.

The caller was from Scotland but married an American and lives in the U.S. He reported that when each of his children was born, his wife was allowed a mere six weeks of paid maternity leave, then she had to return to work. By comparison, when his sister gave birth recently in Scotland, by statute her employer was required to provide her with six months of paid maternity leave, to be followed by six more months at half salary if she chose to avail herself of it. “What’s driving me crazy about the conversation so far,” the caller said, “is that everyone is saying what a great and spectacular thing policies like Netflix’s family leave program are. But this is how things should be. Every employer beyond a specified size should have to provide a year’s paid leave. This isn’t a luxury—it’s how people should be treated.”

Rather than getting defensive when conversing with non-academics about sabbaticals, professors should make a similar argument to the one offered by the guy from Scotland. The idea of Sabbath and sabbatical is ancient—most people who know anything about it know that several chapters in the Pentateuch from the Jewish scriptures describe in detail how a scheduled change in the daily, monthly, yearly routine is to be a fundamental part of the fabric of Israelite life.  Not just for people, but also for the land, for non-human animals, and even for God itself if the divine seventh day rest in the first chapter of Genesis is to be taken seriously.

Not just for people, but also for the land, for non-human animals, and even for God itself if the divine seventh day rest in the first chapter of Genesis is to be taken seriously.

Why are the Sabbath and sabbatical years commanded in the Jewish law? Not because the children of Israel worked harder than anyone else or because they deserve it more than other human beings, but because the rhythms of work and rest, of activity and contemplation, of expending energy and recharging batteries, are built into the very fabric of the world we find ourselves part of. Stepping back and taking a look at things from a different angle in the middle of a culture fully dedicated to manic production and 24-7 work sounds like a quaint luxury, but really it is a psychological necessity.

Joan Chittister, one of the most powerful voices for peace and justice in our world who happens also to be a Benedictine nun, puts it nicely when reflecting on the genius of Benedict’s Rule:

Benedictine leisure is a life lived with a continuing commitment to the development of a culture with a Sabbath mind . . . The purpose of Sabbath is to reflect on life, to determine whether what we’re doing and who we are is what we should be doing and who we want to be. Sabbath is meant to bring wisdom and action together. It provides the space we need to begin again.

The devil, of course, is in the details. Jeanne pointed out that employers could set up programs where employees wanting sabbaticals could have a seventh or a tenth of their salary set aside from each paycheck to accumulate until the seventh or tenth year came—and sabbatical money would be waiting for them. Good start, I say, but I’d go even further—savvy employers will fund these sabbaticals because it will empower their employees in a way that a raise or a couple of extra vacation days could never do. The immediate pushback, of course, is that such a proposal strikes directly at the heart of capitalist efficiency and productivity. To which I respond

I myself am a testimonial to the power of sabbatical. As Joan Chittister writes in the above passage, one of the purposes of sabbatical is to determine whether who we are is who we want to be. During my second sabbatical (I am currently in number four), before I even was consciously aware of it, I started asking that question—and I found that at least in some important parts of my life the answer was “no.” I was not the person I wanted to be. In reflecting, then acting, on that emerging awareness, internal changes occurred that would have never happened without the time and space provided by sabbatical. It offered me the opportunity to begin again and changed my life—I highly recommend it.