A couple of years ago, I was interviewed in my office by a reporter from The Cowl, my college’s student-run newspaper. The interviewer was a former student and asked some reallly good questions. For instance, she knew that I have taught at least two dozen sections of General Ethics, the philosophy department’s gateway course into moral philospohy, over the three decades that I have taught at the college.

“You have introduced many students over the years to many different moral perspectives and franemworks. If you reduced the most important lessons of the moral life to one sentence, what would that sentence be” she asked.

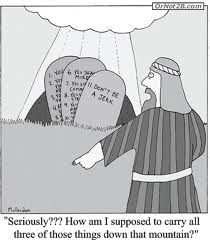

“Don’t be a dick,” I replied

“WAIT! WAIT” I continued, holding my hands up, as soon as I heard the words come out of my mouth. “You can’t write that! say ‘Don’t be a jerk’ instead!” After a few days of nervousness, I was relieved to read in the next edition of The Cowl “Don’t be a jerk” instead of “Don’t be a dick.”

In his lovely little book Wishful Thinking, Frederick Buechner suggests that what we often dismiss as “coincidence” might instead, for those inclined to pause for a moment, provide evidence of something going on behind the scenes. The friend you have been out of touch with unexpectedly calls or emails just as you were thinking about her for the first time in weeks. One of your favorite authors references a text from the Jewish scriptures on page two of her new book that just arrived in the mail from Amazon, the very same text you identified as your favorite verse from the Bible in an after-church seminar the day before. “Weird,” you think—then dismiss it as a coincidence. Don’t do that, Buechner advises. Better, at least on occasion, “to take seriously the possibility that there is a lot more going on in our lives than we either know or care to know.”

In my family, we call such unexplained coincidences “Big Bird moments,” in honor of Jeanne’s brilliant decision to refer to the Holy Spirit as “Big Bird” when trying to talk about things sacred with the eight- and five-year-old stepsons she inherited when she decided that I was worth taking a chance on many years ago. I had one of these “coincidences” not that long ago, one that reminded me that, to use another favorite passage of mine from literature, “there are more things in heaven and earth . . . than are dreamed of in your philosophy.” Although most Big Bird moments are tinged with positive and affirming energy, this recent “coincidence” was a sobering reminder that I should always be careful of what I am saying. Someone is listening.

In my family, we call such unexplained coincidences “Big Bird moments,” in honor of Jeanne’s brilliant decision to refer to the Holy Spirit as “Big Bird” when trying to talk about things sacred with the eight- and five-year-old stepsons she inherited when she decided that I was worth taking a chance on many years ago. I had one of these “coincidences” not that long ago, one that reminded me that, to use another favorite passage of mine from literature, “there are more things in heaven and earth . . . than are dreamed of in your philosophy.” Although most Big Bird moments are tinged with positive and affirming energy, this recent “coincidence” was a sobering reminder that I should always be careful of what I am saying. Someone is listening.

After many years of teaching, my internal file titled “Memorable Students” is getting rather full. I have pictures of some of these students in my office, I am reminded of others when I write a reference letter for a current student and see the names of memorable students from the past whom I’ve written such letters over the years when I file the current reference. “I wonder what she’s doing now?” I think. “He’s probably running his own company.” But there are some students who stick in my memory for no good reason other than that, like an annoying tune you hear in a television ad or an unwanted guest, they refuse to leave once they’ve gained access. Walter was one of those students.

Walter was in my DWC seminar group for both semesters of his freshman year several years ago. He was at or close to the bottom of the seminar group by every measurable standard—he didn’t participate much, wrote poorly, and bombed the midterm and final exams, managing to scrape out a passing grade both semesters by the skin of his teeth. I wanted Walter to do well, because he clearly (at least in my “expert” opinion) was out of place at our college. I resonated with him because he was the sort of kid who undoubtedly was picked on unmercifully in primary and secondary school—skinny, painfully introverted, socially inept, a loner. I knew whereof I spoke, since I was that kid in primary and secondary school.

Walter showed up in one of my classes the next year as a sophomore, this time in a colloquium that I was teaching for the first time with a colleague from the history department. I was, admittedly, relieved when I saw that Walter was in my colleague’s seminar group rather than mine. “I dealt with him for two semesters last year,” I thought. “Now it’s someone else’s turn.”

The capstone evaluation in this course is a half-hour oral exam with my colleague and me. We provide students prior to the exam with four questions to help them prepare, letting them choose which question to begin the conversation with, while understanding that we may touch base with some of the others as well. Students are allowed to bring notes and texts with them to the oral exam, and they always do—evidence of hours of rereading and study.

Toward the end of the week, it was time for Walter’s exam. He entered the room with no books and no notes; when we asked him which question he wanted to begin the conversation with, he admitted that he hadn’t actually looked at any of the questions. And that was the high point of the oral—it went downhill from there. Walter whiffed at every softball my colleague and I tossed him; every answer he did attempt was built around a mumbled “I don’t know,” or “I don’t really remember that.” It was the most awkward half-hour I’ve ever spent with a student. “At least it wasn’t a Walter” became a code phrase between my colleague and me over the years, as we taught the course several more times, for “it could have been a lot worse.” And except for an occasional glimpse from across the arena at a hockey game, that was the last I ever saw of Walter.

Two years later, my colleague and I were finishing up another semester of this course (the third time through). The room in which we were holding the orals was across from the faculty break room; my colleague and I would often refill our coffee cups and stretch our legs there in the ten minutes between each exam. During one break, another colleague from the English department was in the break room and asked how the orals were going.

My teaching partner and I both agreed that, overall, this set of orals was the best of the three iterations of the course over the past four years. Even those students who struggled a bit with nerves and introversion were prepared and did well. “And none of them have been a Walter,” my colleague said. In response to our English colleague’s quizzical look, I took the opportunity to describe in some animated detail over the next couple of minutes the disaster that had been Walter’s oral. It was the Platonic form of academic catastrophe. If you looked up “bad oral exams” in the dictionary, the definition would be a description of Walter’s oral accompanied by a picture of Walter. We all had a good laugh—what professor doesn’t have their “worst ever” examples of every kind of assignment?—and my colleague and I headed across the hall for the next oral exam.

Just as Walter came walking around the corner. I kid you not. It was a WTF, spit-your-coffee-out-all-over-the-wall sort of moment. I had not seen Walter in three years, and there he was seconds after I completed an over-the-top exercise in throwing him under the bus. You can’t make this shit up. My colleague and I, pretending that nothing unusual had happened, invited our next student in for her exam and proceeded in a “nothing to see here” manner. It wasn’t until the next day, in the privacy of his office, that my colleague said “Vance, what are the chances that . . .”—and we both collapsed into embarrassed laughter before he finished his question. I’m quite certain–I sincerely hope–that Walter did not hear any of our conversation in the break room the day before. I’m not sure he even recognized me, and I have no idea of why the hell he was walking down the hall at just that moment.

But I actually think I do know why he was walking down the hall at just that moment. As I thought about this event over the succeeding weeks and months, I realized that Walter had become a placeholder in my imagination for the category “Loser” that I regularly criticize Donald Trump for using. Without knowing a single thing about Walter other than that he struggled academically in my classes, I had turned him into my internal definition of failure.

In his discussion of “coincidence,” Frederick Buechner writes,

Who can say what it is that’s going on, but I suspect that part of it, anyway, is that every once and so often we hear a whisper from the wings that goes something like this: “You’ve turned up in the right place at the right time. You’re doing fine. Don’t ever think that you’ve been forgotten.”

I agree. But the whisper from the wings that I heard when Walter walked around the corner that day was more like “Morgan, stop being a jerk.”