Hey Justin! What if you had a ring that made you invisible when you put it on? Would you use the ring to take the books you’ve been wanting from the kid’s section at the bookstore the next time we go to the mall?

Hey Justin! What if you had a ring that made you invisible when you put it on? Would you use the ring to take the books you’ve been wanting from the kid’s section at the bookstore the next time we go to the mall?

No.

Why not?

Because someone would know.

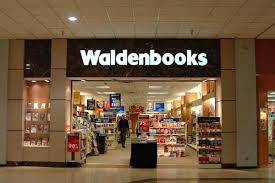

In the summer of 1989, as I prepared for my first PhD-candidate solo flight in the classroom scheduled for the coming fall semester, I solicited advice from anyone and everyone in the philosophy department, from fellow grad students to those breathing the rarefied air of full professor, about what to include in my introductory level ethics class. There were as many “must do” suggestions as there were colleagues. But they unanimously agreed on one suggestion—I had to put Plato’s Ring of Gyges story from Book II of the Republic on the syllabus. A guy who finds a ring of invisibility and uses it to seduce the queen, kill the king, and become top dog in the kingdom of Lydia. Using my seven-year-old son as a guinea pig, I asked him what I would be asking my students in a few months—What would you do with the ring?

How are they going to explain the books floating out of the store?

Well, what if anything you touch or hold when you’re wearing the ring becomes invisible? Now would you take the books?

No.

Why not?

Because someone would know.

I wrote last Friday about my belief that this little story tucked into the early pages of the Republic was the inspiration for the Ring of Power at the center of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, an epic tale that teases out the moral issues and implications of such a scenario.

The ring put immediate pressure on each person’s most sensitive areas—what do you really want? In what ways are you hindered from getting what you want by obedience to moral norms? What would you do if the pressure to abide by moral norms were lifted? Justin, living in a house with an academic father and step-mother, was a great lover of books and regularly received a “no” answer to his requests to buy more books when visiting the local bookstore (we were living on a tight graduate student budget, after all). The ring of invisibility would give him direct access to the world he really wanted—one filled with every book his heart desired.

There would be spaces on the bookstore shelves where I took the books from.

So you fill those holes up with books from some other part of the store that no one’s looking at. Now would you take the books?

No.

WHY NOT?

Because someone would know.

More than twenty-five years later, I would guess that I have taught  a class focusing on the Ring of Gyges at least fifty times. The story teaches itself. It is an extraordinarily flexible tool to get people of all ages and various life experiences to start immediately thinking about why they follow moral guidelines and principles at all. As the director of a large interdisciplinary humanities program, I am frequently asked to give “mock lectures” to weekend groups ranging from alumni and board members to prospective students and their parents. One of my two “go to” lecturse for such events is “The Ethics of Invisibility: Plato’s Republic and Gyges’ Ring.” After a few minutes of set-up, I ask my audience what I asked my son all those years ago—suppose you had the ring of invisibility. Do you think you would find yourself doing things when wearing the ring that you don’t normally do?

a class focusing on the Ring of Gyges at least fifty times. The story teaches itself. It is an extraordinarily flexible tool to get people of all ages and various life experiences to start immediately thinking about why they follow moral guidelines and principles at all. As the director of a large interdisciplinary humanities program, I am frequently asked to give “mock lectures” to weekend groups ranging from alumni and board members to prospective students and their parents. One of my two “go to” lecturse for such events is “The Ethics of Invisibility: Plato’s Republic and Gyges’ Ring.” After a few minutes of set-up, I ask my audience what I asked my son all those years ago—suppose you had the ring of invisibility. Do you think you would find yourself doing things when wearing the ring that you don’t normally do?

Who is going to know??!!

I’ll set off the alarm at the front of the store when I walk out.

So let’s say that when you’re invisible the machine can’t detect you or anything you are holding! NOW are you going to take the books?

No.

WHY NOT??

Because someone would know.

Except the occasional goody-two-shoes who claims she would use the ring for good (no guy has ever claimed this), virtually every one of my classroom companions admits that they would behave differently when wearing the ring than they normally do, pressing and eventually breaking through the envelope of basic moral expectations. When asked for specific examples, people usually start small.

- Listen in on conversations you have not been invited to be part of.

- Play tricks on your friends.

- Steal something small and insignificant, just to verify that the ring actually works.

To raise the bar a bit, I ask “how many of you would use the ring to give yourself a free upgrade to first class instead of sitting in the cheap seats in the back the next time you are on a plane?” Almost everyone always admits that they would. When asked why they don’t give themselves such an upgrade without the ring, the answer is never “Because it’s wrong.” Rather, we don’t give ourselves free upgrades because we are afraid we’ll get kicked off the plane if our theft is discovered. Which is exactly the point of the Ring of Gyges scenario—we behave morally because we fear the consequences of not doing so. As soon as we are convinced that “no one will know” if we do something immoral, a world that the ring of invisibility places within our grasp, our commitment to moral behavior vanishes just as we do when we wear the ring.

To raise the bar a bit, I ask “how many of you would use the ring to give yourself a free upgrade to first class instead of sitting in the cheap seats in the back the next time you are on a plane?” Almost everyone always admits that they would. When asked why they don’t give themselves such an upgrade without the ring, the answer is never “Because it’s wrong.” Rather, we don’t give ourselves free upgrades because we are afraid we’ll get kicked off the plane if our theft is discovered. Which is exactly the point of the Ring of Gyges scenario—we behave morally because we fear the consequences of not doing so. As soon as we are convinced that “no one will know” if we do something immoral, a world that the ring of invisibility places within our grasp, our commitment to moral behavior vanishes just as we do when we wear the ring.

As time allows me to push the envelope even further with my audience, I generally find that there is a moral glass ceiling through which very few people are willing to crash wearing the ring, even when it is guaranteed that they will never be held accountable for what they do. Other than the random person (always a guy) who says he would use it to kill people he doesn’t like, everyone stops short of murder. Many would stop long before travelling that far along the path. But only rarely is there someone like my seven-year-old son who says he would not use the ring at all. What is wrong with people like that?

YOU’RE FREAKING INVISIBLE!! NO ONE’S GOING TO KNOW!!

I would know.

Out of the mouths of babes, as the saying goes. Where did my seven-year-old get a moral compass so true that it could (might) override even one use of the ring of power? Perhaps Jeanne and I had already brainwashed him sufficiently in the rules of proper human conduct. I doubt it. Tolkien was right when he suggested that the seemingly simple hobbits Frodo and Sam were the most appropriate persons in Middle Earth to deal with the ring—moral strength disguised as simplicity. Perhaps it really is as basic as what it says in Deuteronomy: “The word is very near you, in your mouth and in your heart, that you may observe it.” Worth remembering the next time I am tempted to see what I can get away with. Someone would know.

Out of the mouths of babes, as the saying goes. Where did my seven-year-old get a moral compass so true that it could (might) override even one use of the ring of power? Perhaps Jeanne and I had already brainwashed him sufficiently in the rules of proper human conduct. I doubt it. Tolkien was right when he suggested that the seemingly simple hobbits Frodo and Sam were the most appropriate persons in Middle Earth to deal with the ring—moral strength disguised as simplicity. Perhaps it really is as basic as what it says in Deuteronomy: “The word is very near you, in your mouth and in your heart, that you may observe it.” Worth remembering the next time I am tempted to see what I can get away with. Someone would know.