Upon hearing a week ago that Muhammad Ali had passed away, I posted something very simple on Facebook and Twitter: “Muhammad Ali’s sports nickname says it all. He was simply The Greatest.” Jeanne and I left shortly afterwards for a weekend trip to Pennsylvania, so I did not get to see or hear the dozens of tributes from across the globe both mourning the champ’s passing and celebrating his remarkable life until returning home. Ali won the heavyweight boxing championship for the first (of three) times when I was a young kid; my growing up years were regularly marked by the latest explosion of this very public man’s life into the news from the boxing ring and the court room. What possible impact could the life of a Muslim, African-American boxing champ have on a white boy as he inched toward adulthood in northern Vermont? A significant one, as it turns out.

Jeanne and I left shortly afterwards for a weekend trip to Pennsylvania, so I did not get to see or hear the dozens of tributes from across the globe both mourning the champ’s passing and celebrating his remarkable life until returning home. Ali won the heavyweight boxing championship for the first (of three) times when I was a young kid; my growing up years were regularly marked by the latest explosion of this very public man’s life into the news from the boxing ring and the court room. What possible impact could the life of a Muslim, African-American boxing champ have on a white boy as he inched toward adulthood in northern Vermont? A significant one, as it turns out.

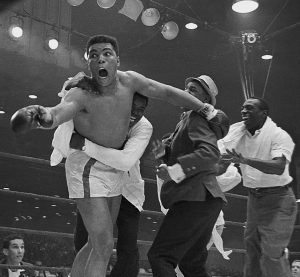

I was eight years old when Cassius Clay won the heavyweight boxing championship at the age of twenty-three, defeating the fearsome Sonny Liston in one of the greatest upsets in boxing history. He was loud, brash, an entertainer, extremely confident and full of himself—and was poetry in motion. I was used to watching the Friday night fights with my father on television when he was not on the road, but I’d never seen anything like this guy—a heavyweight who moved like a middleweight. As a white boy growing up in northern Vermont, I was mildly aware of what was going on in the early Sixties—the civil rights movement, early resistance to the Viet Nam war, the counter culture—but the champ was the first public figure who embodied all of it for me. When, shortly after winning the title, the new champ announced that he was a member of the Nation of Islam, that he was rejecting his “slave name” Cassius Clay for a new name—Muhammad Ali—then that he was refusing to be drafted, confusion and cognitive dissonance reigned at my house. My father was a big boxing fan and had declared Clay (he wasn’t inclined yet to accept the champ’s new name) the best boxer he had ever seen (and Dad remembered Sugar Ray Robinson and Joe Louis). But my father found it hard to believe the Nation of Islam business and declared the champ to be a traitor and coward for refusing to serve his country (even though my father had escaped the draft during the Korean War, due to a deferment available to seminarians).  I knew no black people and knew nothing about Islam, but was intrigued by Ali’s principled stand and refusal to compromise his beliefs—even if I didn’t know or understand exactly what they were.

I knew no black people and knew nothing about Islam, but was intrigued by Ali’s principled stand and refusal to compromise his beliefs—even if I didn’t know or understand exactly what they were.

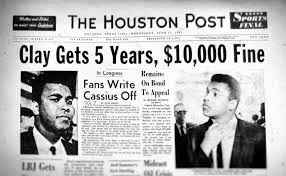

Because he refused to be inducted into the Army, in 1967, Muhammad Ali was stripped of his title, forced to surrender his passport, and could not get a license to fight for three-and-a-half years. By the time the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction in 1971, attitudes concerning his resistance to the war had changed, both across the country and in my family. My father, who had originally called Ali a coward and traitor, came to understand along with many others that Ali’s resistance to the war was absolutely right, just four or five years ahead of its time. My Dad testified in front of our local draft board in support of my older brother’s case for conscientious objector status in the early seventies— I have no doubt that Muhammad Ali’s stand had something to do with my father’s change of heart.

I have no doubt that Muhammad Ali’s stand had something to do with my father’s change of heart.

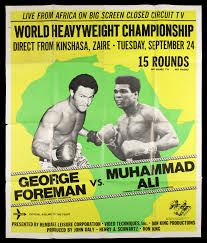

Ali’s greatest fights happened during my high school and early college years. I watched in disbelief when Ken Norton broke Ali’s jaw and handed him only his second career defeat. I skipped class my freshman year in college to listen to the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Zaire on the radio. In what was perhaps the greatest sporting spectacle of the twentieth century, very few gave Ali a chance against the devastatingly powerful and much younger champion George Foreman—but he knocked George out in the eighth round. I skipped class once again a year later and listened to the “Thrilla in Manila,” the rubber match in Ali’s epic three fight rivalry with Joe Frazier.  Ali won what was perhaps the greatest boxing match in history with a fifteen-round unanimous decision. But for me, Ali’s larger-than-life persona was even more riveting than his boxing. Looking underneath Howard Cosell’s toupee during an interview; getting into a scuffle on air with Joe Frazier during another Cosell interview prior to their second fight; breaking into impromptu rhyme at the drop of a hat; cleverly insulting his opponent speechless prior to each fight—I loved everything about him. When ESPN awarded it’s “Athlete of the Century” to Michael Jordan instead of Muhammad Ali at the close of the twentieth century, I dismissed their decision as a laughable mistake. Ali not only transcended his sport—he changed the world.

Ali won what was perhaps the greatest boxing match in history with a fifteen-round unanimous decision. But for me, Ali’s larger-than-life persona was even more riveting than his boxing. Looking underneath Howard Cosell’s toupee during an interview; getting into a scuffle on air with Joe Frazier during another Cosell interview prior to their second fight; breaking into impromptu rhyme at the drop of a hat; cleverly insulting his opponent speechless prior to each fight—I loved everything about him. When ESPN awarded it’s “Athlete of the Century” to Michael Jordan instead of Muhammad Ali at the close of the twentieth century, I dismissed their decision as a laughable mistake. Ali not only transcended his sport—he changed the world.

The most lasting memory of Muhammad Ali for many people is probably his lighting of the Olympic torch to officially start the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta.  Afflicted with Parkinson’s disease for more than a decade, the image of an obviously frail and shaking Ali completing his task successfully was truly compelling. Many of the tributes in the days following his passing focused on that image, as well as his philanthropic work; they were remembering a kind and generous ailing elder statesman. That’s a worthy tribute, but that is not the man I remember, the man who regularly burst into my early years in various ways. Muhammad Ali was an original, edgy, flamboyant, and always a bit scary. My people became comfortable with Dr. King’s role in the civil rights movement over time,

Afflicted with Parkinson’s disease for more than a decade, the image of an obviously frail and shaking Ali completing his task successfully was truly compelling. Many of the tributes in the days following his passing focused on that image, as well as his philanthropic work; they were remembering a kind and generous ailing elder statesman. That’s a worthy tribute, but that is not the man I remember, the man who regularly burst into my early years in various ways. Muhammad Ali was an original, edgy, flamboyant, and always a bit scary. My people became comfortable with Dr. King’s role in the civil rights movement over time, but Ali was in the mold of Malcolm X. Angry, abrasive, eloquent, successful—and not the least bit concerned with playing any of the roles or saying any of the things that white folks expected black athletes and public figures to do or say. He refused to accept the world he was born into, and throughout his life he explored his power to change it.

but Ali was in the mold of Malcolm X. Angry, abrasive, eloquent, successful—and not the least bit concerned with playing any of the roles or saying any of the things that white folks expected black athletes and public figures to do or say. He refused to accept the world he was born into, and throughout his life he explored his power to change it.

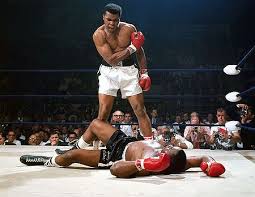

My son Justin, was born just a couple of weeks before Ali retired for the last time in late 1981 after making one too many comebacks, as many aging athletes do. We talked on the phone a few days after the champ died; Justin told me that for many years, first in his dorm room, then in the bedroom of various apartments, he hung the iconic picture of Ali yelling for Sonny Liston to get up after knocking Liston out with one devastating punch less than a minute into the first round of their second bout. “He was one of my heroes,” Justin said. That makes sense, because he was one of mine as well. He was simply The Greatest.