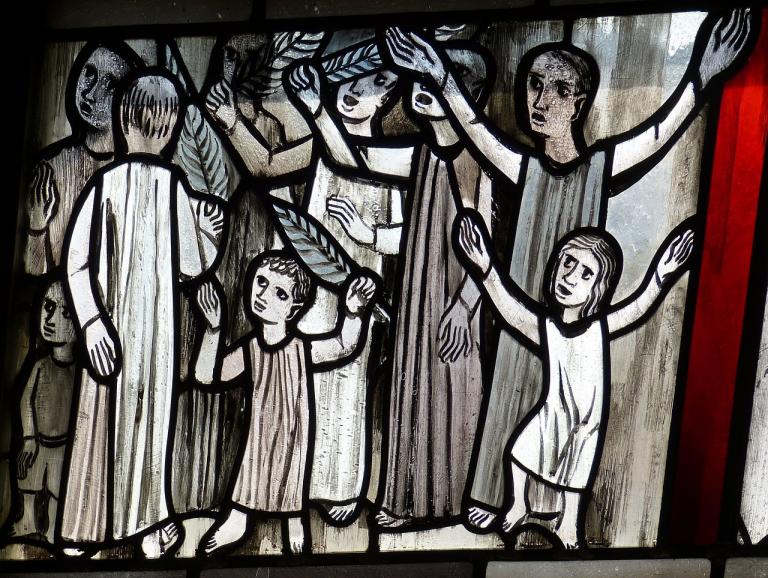

Today is Palm Sunday, one of the most dramatic days on the liturgical calendar. But there is one reported event attributed to Palm Sunday that it makes an appearance in the liturgy every Sunday. And each time I say or sing this part of the liturgy, I remember a beloved colleague.

Rodney Delasanta was one of best teachers and colleagues I ever had the privilege of knowing. Rodney was a true Renaissance man—a Chaucer scholar, family man, sports fan (especially the Red Sox), award-winning accordion player (really), and classical music aficionado. The accordion business made him a regular recipient of the latest accordion joke from me. “What is the definition of a gentleman? A man who knows how to play the accordion—and doesn’t.” Once Rodney responded with an even better one: An accordion player is trying to find the location of his latest gig in downtown Manhattan. He parks his station wagon on the street with his accordion in the back, locks it, and sets out on foot to find the address. Upon returning to his vehicle he is crestfallen to find that the back window has been broken—and even more crestfallen to find five more accordions in the back of the station wagon!

Rodney lived fifteen miles from campus, and told me shortly after we met that he had spent the past several months of commuting (fifteen miles is a very long commute in Rhode Island) listening to Bach’s Mass in B minor, about which he was as exuberantly effusive as he was about life in general. He was particularly taken by Bach’s setting of the Sanctus in this composition. According to Isaiah’s vision of the throne of God, the angels continually sing “Holy, Holy, Holy, is the Lord God of Hosts; heaven and earth are fully of His glory.” This inspired Bach’s setting, music that Rodney, in his usual measured fashion, declared to be the “most glorious six minutes of music ever written.”

Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus Holy, Holy, Holy Lord

Dominus Deus Sabaoth, God of power and might

Pleni sunt coeli et terra Heaven and earth are full of Your glory

Gloria eius. Hosanna in the highest

I miss Rodney. He died of cancer several years ago; the nine years I spent teaching honors students on an interdisciplinary team with him during my early years at Providence College strongly influenced me both as a teacher and a human being. I cannot listen to any setting of the Sanctus, particularly Bach’s, without thinking of Rodney fondly.

With fewer than six degrees of separation, this makes me think of Mary Doria Russell’s science fiction novel The Sparrow. It is a wonderful story with a fascinating premise: Life is discovered on another planet through transmissions of hauntingly beautiful music, to which scientists respond with transmissions of their own, including selections from Bach’s Mass in B minor (Rodney would have approved). Eventually an expedition, including Jesuit explorers and scientists, make first contact — just as Jesuit priests were often in the vanguard of Europe’s Age of Discovery. “Catholics in Space”—it’s a great premise.

The mission goes disastrously and terribly wrong, leaving one of the Jesuits, Emilio Sandoz, as the sole survivor. Sandoz believed that God had led him to be part of this mission, that God had micromanaged the details to bring it about, and thought he was in the center of God’s will. In the tragic aftermath, after all of his companions are horribly killed, he is devastated, ruined physically, emotionally, and spiritually. From the depths of his pain he lashes out at God: “I loved God and I trusted in his love . . . I laid down all my defenses. I had nothing between me and what happened but the love of God. And I was raped. I was naked before God and I was raped.” Only such blunt and brutal words can match his devastation. In conversation with fellow priests and his religious superiors back on Earth, Emilio says “It wasn’t my fault. It was either blind, dumb, stupid luck from start to finish, in which case we are all in the wrong business, gentlemen, or it was a God I cannot worship.”

The God of Power and Might responds, “Oh, really??” We already have a classic text on what this God has to say in response to demands for accountability—the book of Job. There are a number of parallels between Emilio and Job: both are dedicated believers, both are all but destroyed by events surrounding them, and neither carries any blame for these disastrous events. Job, from the midst of the ash heap in which he sits, demands an accounting from God just as Emilio does from the midst of his devastation. God’s answer to Job, once he bothers to provide one, is along the lines of “Who are you, puny creature, to question anything about me or what I do? I’m God, you’re not, so let me offer you a large helping of ‘shut the hell up’.”

And a God of Power is entirely within its authority to give such an answer. Some afflicted believers, in the face of such a response, might say with Job “though He slay me, yet I will trust Him.” Others might rather say, with Emilio, “Fine, but this is a God I cannot worship.” In Emilio’s position, I would say the same thing. Thanks for sharing (finally), but you can’t do any worse to me than you’ve already done. I’m outta here.

The God of Glory and Mystery responds “As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, and my thoughts than your thoughts.” This, I suppose, is an improvement on “I’m God and you’re not,” but not much of one. The God of Mystery’s answer is a reminder that none of our human faculties, either individually or as a total package, can ever crack God’s code, can ever fully encompass divine reality. I’m sure this is true, but it can easily turn into a license for laziness and apathy. The greatest commandment is to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind.” If my heart, soul, and mind are incapable of touching the transcendent, then God can be whatever I want God to be, since all visions of God are equally immune from scrutiny. Let’s just make it up as we go along.

But there is another divine response. The God of Love created the world because, as Iris Murdoch writes, “He delights in the existence of something other than Himself.” But love limits power. In order for the loved to exist and respond to love freely, the lover must not manipulate or control. The language of love is the language of intimacy and vulnerability. The only possible response of the God of Love to suffering, pain, and anguish is to embrace and endure it with us, rather than to eliminate it. And the ultimate response of the God of Love to human pain is to become human. This is not a God who intercedes. This is a God who indwells. God comes as one of us, not as a distant source of arbitrary power or wrapped in a cloud of mystery.

The ancients had it easy, because the various and indefinite aspects of the transcendent were each given shape in a different deity. Power for Zeus, wisdom for Athena, erotic love for Aphrodite, mischievous creativity for Hermes, murderous tendencies for Ares, plain old hard work for Hephaestus—a different deity for every divine mood. Maybe monotheism isn’t such a good idea. But the God of Love is a good way to get a monotheistic handle on our polytheistic dealings with the divine. The God of Love chooses to ratchet down divine power in exchange for relationship.

The God of Love is revealed in the most intimate mystery of all, God made flesh. God responds to our demands for answers strangely—nothing gets answered, but everything is changed. Christianity does not provide a supernatural cure for suffering, but a supernatural use for it. Christ in us, the hope of glory. In the liturgy the Sanctus is followed by the Benedictus—“Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord,” exactly what the crowds are singing to Jesus on a donkey as the drama of Holy Week begins today. “Hosanna in the highest” indeed.