The other day upon returning from her early morning visit to the gym, the first thing Jeanne said was “I was listening to an episode of ‘Throughline’ on the radio that you will love! It’s all about the problem of evil—they were just starting to talk about Hobbes when I got home!” Not many people’s spouses get excited about conversations that focus on 17th century English philosophers, but she knows me well. We listened to the podcast together later the next day as we were getting ready for supper. Here’s the link in case you are interested (you should be!).

https://www.npr.org/2023/01/24/1151023362/when-things-fall-apart

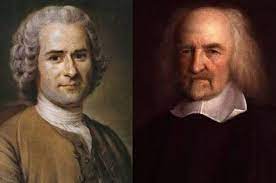

I often tell my students that by far the most interesting philosophical subject is us—human beings. And central to philosophical investigations of human beings is the question of what we are by nature, apart from and prior to culture and societal influences. When attempting to tease out what is “nature” in human beings and what is “nurture,” philosophers have often sought to imagine what the “state of nature,” an existence prior to civilization, society, and urban life, must have been like for human beings. Which brings us to Thomas Hobbes.

Thomas Hobbes lived during the English Civil War and had first-hand experience with the worst that human beings can be. In his greatest work, Leviathan, Hobbes imagined the state of nature to have been violent and destructive, a world in which the natural aggression of human beings dominated in a “survival of the fittest” mode, as he describes in this famous passage:

In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; And the life of man: solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

As an aside, the biggest laugh I ever got in a classroom was when I noted that Hobbes’ famous phrase “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” reminded me of my ex-wife. Hobbes argued that human beings enter into society and the social contract in order to protect themselves and their interests from the threat of other people.  We create communities with laws, norms, and restrictions on our natural impulses, in other words, in order to protect ourselves from each other

We create communities with laws, norms, and restrictions on our natural impulses, in other words, in order to protect ourselves from each other

Other philosophers, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century, imagined the state of nature as idyllic and simple, a world in which human beings’ natural goodness ruled. Rousseau believed that most, if not all, of the evils of the world and in human behavior is due to the corruption of our natural goodness by the pressures and temptations of society, describing his imaginary person in the state of nature as follows:

If we strip this being, thus constituted, of all the supernatural gifts he may have received, and all the artificial faculties he can have acquired only by a long process; if we consider him, in a word, just as he must have come from the hands of nature, we behold in him an animal weaker than some, and less agile than others; but, taking him all round, the most advantageously organized of any. I see him satisfying his hunger at the first oak, and slaking his thirst at the first brook; finding his bed at the foot of the tree which afforded him a repast; and, with that, all his wants supplied.

According to Rousseau, our life in the state of nature was actually pretty good. We were healthy, had lots of exercisealong with a varied diet; things were peaceful as well. But everything went wrong when we gave up our liberty, invented private property, and settled down in villages and cities, thus creating this thing called civilization.

Often what is “natural” is considered to be what is “best,” even in the moral life–but that depends on what we are really like naturally. Which of the above visions of the state of nature–that Rousseau’s or Hobbes’–is more likely to be accurate? This is more than a merely academic or blog post exercise. As the “Throughline” podcast points out, how we think about societal organization, the workplace, education, politics, and more depends on what we truly are at our core.

If you believe that kids are fundamentally lazy and selfish, then you need a quite hierarchical schooling system. But if you think that kids are naturally curious and creative, then maybe you don’t need, you know, all that homework. Maybe you can just give kids the freedom to decide for themselves what they find interesting. If you are the CEO of a company, if you believe that your employees are fundamentally selfish, well, what are you going to do? You need a lot of bureaucracy, probably. Maybe you’re going to place cameras to make sure that your employees don’t steal equipment.

If you believe that your employees are fundamentally cooperative and actually wanna do what’s best for the company, then maybe you can work in self-directed teams and you don’t need all those managers, and you can actually rely on people’s intrinsic motivation. So again and again, again and again, our view of human nature has pretty practical implications for how we live our lives.

And, of course, much of the political polarization in our country demonstrates the stark differences between Hobbesian and Rousseauvian assumptions concerning human nature. From a Hobbesian perspective, on the one hand, strong government and law enforcement is needed from the top down, the assumption always being that people are inclined to behave in their exclusive self-interest and will act badly and violently unless controlled in various ways. Fear tends to be the primary factor in maintaining the social order.

On the other hand, Rousseau’s more positive perspective concerning basic human nature leads to a greater basis for hope in the future, regardless of how bleak the present might seem. Martin Luther King Jr.’s hopeful claim that “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice” can become more than a utopian platitudinous vision only if there is a fundamental goodness in human beings that can over time bend that arc. As one of the interviewees in the “Throughline” podcast observes,

I’ve always believed in the power of utopia, thinking every milestone of civilization, the end of slavery, democracy, equal rights for men and women. These were all utopian fantasies once until they happened. That’s why I think that history is actually the most subversive discipline of all the social sciences because history shows us that things can be different. They don’t have to be this way. We can change them. We have to believe in the power of hope. If you believe in hope, if you’re actually hopeful for the future, then you know you have to do something.

There is far more in this issue than can be considered in one blog post—more will be coming soon. One final thought, though. It’s worth noting that Thomas Hobbes wrote not only wrote in an England in the midst of a bloody civil war, but also wrote in a very Christian society that was heavily influenced by the Protestant Reformation that began a century and a half earlier. One of the most basic tenets of various versions of traditional Christianity, particularly conservative Protestantism, is the utter depravity of human nature. Tell whatever story you want—original sin, eviction from the Garden Eden, influence of dark forces—the claim is that human beings are fundamentally flawed by nature and can do nothing to fix the problem. Hence the need for salvation.

In the meantime, the only way to keep such creatures under control is with strong authoritarian influence throughout society. If you want to know why a wannabe authoritarian like Donald Trump continues to garner strong support from among white conservative evangelical Christians despite his moral failings and legal troubles, this is a good place to start. If you live in fear of others and consider this world to be little more than a difficult and problematic temporary stop on the way to eternal bliss, why wouldn’t you want someone in control who clearly has authoritarian tendencies?

Stay tuned!