Christmas movies are a big deal at my house. Jeanne goes for the classics, such as “Miracle on 34th Street,” “The Bishop’s Wife,” “It’s a Wonderful Life,” and (her favorite) “White Christmas.” Those are all fine (except “White Christmas,” which I can take or leave), but I tend to favor more recent ones, like “The Holiday” and (my favorite) “The Nativity Story.”

Movies with Biblical themes were both attractive and problematic in my early years. We did not go to movies, but it was okay to watch them on TV (go figure), except on Sundays (go figure again). Of particular interest were Hollywood epics of Biblical proportions, such as “The Ten Commandments,” “Ben Hur,” “The Robe,” and “Quo Vadis.” Moses always has, in my imagination, looked like Charlton Heston (and, I guess, like Ben Hur). Even more daring were the various Hollywood portrayals of Jesus, from “muscular Jesus” in “King of Kings” and “cerebral Jesus” in “The Greatest Story Ever Told” to, some years later, “ethereal and almost effeminate Jesus” in “Jesus of Nazareth.” I have many memories of fellow fundamentalists watching such movies with me and saying “That’s not Scriptural” and “That’s not Biblical” when characters from the sacred text said or did things that were not contained within the leather covers of the King James Version.

“The Nativity Story” would not entirely escape such criticism, but it presents a remarkably straightforward, hence beautiful, rendition of the birth of Jesus narratives. All of the standard elements are there—Elizabeth and Zechariah, Mary and Joseph, shepherds and wise men at the manger, angels in appropriate places saying appropriate things, along with a particularly creepy father and son team of Herod the Great and Herod Antipas. These standard elements, though, arise from a conflation of gospel texts. The authors of Mark and John apparently didn’t think the circumstances of Jesus’ birth important enough to even report on, while the authors of Matthew and Luke construct their stories from “cherry-picked” details. Luke does not mention the wise men or the star, but has angels singing to shepherds, who then visit Jesus in a manger in Bethlehem. Matthew has no worshipping shepherds or even a manger, but wise men following a star visit the holy family in a house, probably in Nazareth, sometime after Jesus’ birth. Throw in Santa and some reindeer, and you’d get the usual front lawn decorations for the holiday season.

So where lies the truth? A friend who passed away a couple of years ago tended to be rather definitive in his pronouncements. Once at lunch he said that “The heart of Christianity is what you believe about the stories. Do you believe the stories are true or don’t you? Yes or No? And if you say ‘let me think about it,’ that’s the same as saying No!” This was not directed at me specifically—he was just drawing a line in the sand, as those of us who know and love him expect him to do. But I think I’m in trouble. Because not only am I not sure about whether my answer to his question is “yes,” “no,” “let me think about it,” or even “which stories are you referring to?”—I’m inclined to say that “it doesn’t matter.”

Toward the end of every fall semester, I spend a couple of weeks in the New Testament with a classroom full of college freshmen in the interdisciplinary course I teach in. Knowing that this was a group, largely the product of twelve years of parochial school education, for whom the Bible in college might be a tough sell, one year I asked my seminar group an out of the box question right at the start: What difference does it make whether these stories are or aren’t true? If it were definitively proven tomorrow that Jesus never existed, then what? A fascinating discussion ensued, full of more nuance and insight than even I expected. Contributions ranged across the spectrum of possibilities, but one student’s comment particularly stayed with me. “I’d still be a Christian,” she said, “because being a Christian makes me a better person than I would be if I wasn’t.” That’s a good start—the measure of one’s faith is what impact it has in real time on the life being lived.

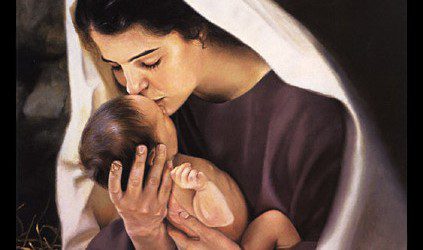

Meister Eckhart once said that the virgin birth is something that happens within us, that the nativity story is the story of the continuing union of the Spirit of God with individual, fleshly human beings. But then Meister Eckhart was accused of heresy, was fortunate to escape being burned at the stake, and died in obscurity. No wonder I resonate with his insight. At the climatic manger scene in “The Nativity Story,” the gold-bearing wise man Melchior, who looks amazingly like a colleague and friend of mine in the history department, gazes at the baby and says “God made into flesh.” There it is in its simplicity and iconoclasm—the heart and soul of Christianity. God made into flesh.

When did the Incarnation become “mine” for the first time? Was it when I consciously noted new space deep inside of me while reciting a Psalm at noon prayer? Was it when I realized that I was no longer angry at people and issues from my past that had consumed my life? Was it while playing hide-and-seek with a couple of deer on a trail? Was it when I heard Catherine of Genoa’s “My deepest me is God” in a homily? It truly doesn’t matter when it happened, just that it did. On good days, I can look at another human being and detect holiness. On really, really good days, I can even turn my eyes inward and find something beautiful. I can say, with gratitude, awe, and disbelief all tangled together, along with Melchior gazing at the manger, “God made into flesh.” Remarkably small. Disturbingly fragile. Completely mysterious. And utterly true.

Merry Christmas