I have two book projects in the works these days. I just finished a full rough draft of the first book and have turned it over to a few trusted friends and colleagues for review and input. While that’s going on, my thoughts turn to my second book project, one that I’ve had in mind since before the pandemic. Tentatively titled Nice Work If You Can Get It: Lessons and Stories from a Life in the Classroom, the time has come to stop the material gathering and to start cranking up the writing. Today’s essay is part of that initial cranking activity.

With too much time on my hands the other day, I scrolled through my Facebook feed and came across a meme asking, “What job deserves higher pay?” In knee-jerk fashion, I added my reply to the 300K responses already posted: “Teachers, obviously.” I’m a teacher and I get paid well, but that’s after three-and-a-half decades of incremental progress. That’s also because I have been a tenured full professor for twenty years. The teachers I’m particularly thinking of are those I admire the most—those teaching in elementary and secondary school. I know that I don’t have the patience or courage to teach anyone younger than a freshman in college. Elementary and secondary teachers are my heroes.

Scanning a few of the thousands of responses to the meme question, I noticed that probably 50% of the respondents said “teachers” or something more specific like “public school teachers.” Then some fool named “Jason” posted “Everyone’s saying teachers, but they get three months off a year (real graft).” Practicing my Stoic cool and Christian charity, I simply responded “Jason, you clearly know nothing about teaching. Signed, a teacher.” I’m pleased to report that several others piled on Jason in short order with much more detailed (and direct) criticism, saving me the necessity of doing so myself.

This is probably not the best time for me to note that I am on sabbatical in the fall semester and will not be back in the classroom until the day after MLK Day in January 2024. Furthermore, I will be collecting my regular paycheck every month between now and then. Scam? Graft? Getting paid full time for a part time job? I’m sure Jason would like to comment. I spent much of the early years of my academic career trying to explain to my non-academic relatives and friends why teaching is not a part-time job. Facts such as the requirement to publish articles and books, that one spends roughly four hours outside the classroom on teaching-related tasks for every hour in the classroom, and so on made little impact. Eventually I adopted a response that a colleague from years past said he used when challenged similarly by his family and friends:

Them: It must be nice to get paid full time for a part time job!

Me: It is nice! If you were smart enough you could get that kind of job too!

For years, I have told anyone who would listen that I have the greatest job in the world. Not because of what it pays or because it is a part time job, but because it suits me perfectly, it’s a true expression of my best self, and I’m good at it. It’s a true vocation and calling; if I get theological for a moment, it’s the primary way that I can occasionally be a vehicle of the divine in the world. The practicalities of the teaching profession also make it attractive (to some at least), since variety is built right into the academic year with highs and lows that are both real and largely predictable in broad strokes.

Then there’s the flexibility. Follow any teacher around for a year and you will find that she or he is working something like an average of 40-50 hours per week at least (that’s a full-time job, Jason). But she or he will be doing different things during those weeks depending on the time of year, and often will be doing them at unexpected times (like the middle of the night). Benefits—you get to decide when a lot of your work hours will occur. Downside—it’s very difficult to leave your work at work.

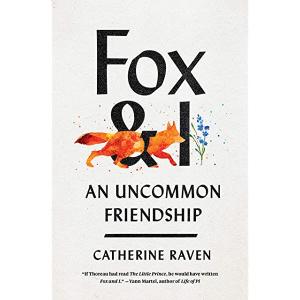

I recently finished reading Catherine Raven’s Fox and I; if you like books about the interactions between non-human living things and human beings, about the glories, wonders, and frequently terrible features of the natural world, and about the dynamics of making important life choices, I highly recommend it. Fox and I is a difficult book to summarize, so in the spirit of well-intentioned plagiarism (something teachers encounter all the time), here’s a paragraph from Amazon’s description of the book:

Fox and I is a poignant and remarkable tale of friendship, growth, and coping with inevitable loss―and of how that loss can be transformed into meaning. It is both a timely tale of solitude and belonging as well as a timeless story of one woman whose immersion in the natural world will change the way we view our surroundings―each tree, weed, flower, stone, or fox.

Throughout the book, Raven struggles with choices between her love of solitude and living remotely in the midst of nature while taking occasional short-term teaching gigs, or taking the next “logical” step from her PhD in biology by landing a full-time university teaching position. Toward the end of the book, she has an epiphany about her own process and struggles that I find very thought-provoking when considering the life of teaching.

I had been trying to define myself with a noun, a title that identified an occupation, while I should have been relying on verbs. Entitling nouns deceive people. Maybe on purpose. I would rather someone tell me that he sings than that he is a singer. The latter phrase is trying to nudge me someplace I may not want to go. He hunts is a specific phrase, weighted with responsibility; he is a hunter implies more than it guarantees. To say “I teach and guide students” seemed more honest than saying, “I’m a professor.” I didn’t need to be. I needed to do . . . How often in our lives do we discover that the source of all our worries is simply a poor grammatical choice?

I have to think about this one for a while, because I take great pride in being a professor. I like the title, the privileges that go with it, and the respect (at least in some quarters).

But Raven’s reflections brought to mind something that an esteemed colleague, a senior faculty member who was one of my mentors during my first years at Providence College, wrote almost twenty years ago when he nominated me for our campus’s Teacher of the Year award (which I won):

[Vance] is the consummate professor, one who “professes” philosophy not as an archaic academic curiosity but as living thought.

It is easy to forget that to “profess,” and similarly to “teach,” is an activity—a verb—while “professor” or “teacher” are nouns that at least imply status, achievement, and responsibilities that perhaps have little or nothing to do with their related verbs.

I fully expect that this helpful insight from Catherine Raven will be an important organizing principle for my book project in the coming weeks. Stay tuned—I usually work these things out on this site!