Yesterday I posted what I wrote the day before the presidential election in 2016. Today I am reposting what I wrote on Election Day in 2020, the second of three consecutive “most important elections of our lifetime.” Other than changing the names of the candidates, I’ve changed nothing else in this post from four years ago. As you’ll see, very little has changed from four years ago.

In 1969, Johnny Maestro and the Brooklyn Bridge released the single ‘Worst That Could Happen”—it went gold. It’s a ballad about how distressing it is to find out that your former girlfriend is getting married to someone who apparently is a much better catch than you were. The psychological angst is caught in the recurring chorus:

Maybe it’s the best thing

Maybe it’s the best thing for you

But it’s the worst that could happen to me

Today is Election Day, actually the culmination of an Election Season that has been going on for several weeks. And no matter how it turns out, millions of people are going to be singing the refrain of “Worst That Could Happen” for the foreseeable future.

If Donald Trump is elected as President for the second time, millions of voters will be bracing themselves for “the worst that could happen” as an already unhinged person enters four years of no apparent roadblocks to continued and accelerated unhingedness, while others will celebrate the unfolding of their version of the best of all possible worlds. If Kamala Harris is elected President, millions of voters will face a “worst that could happen” world in which their favorite leader is gone and the country speeds down the fast track toward socialism, while others celebrate the opportunity to take deep breaths of relief that have been unavailable for four years.

Don’t get me wrong. I believe, as many Americans believe, that this is the most important election of my lifetime; I’ve heard more than one historian say that it might be one of the two or three most important elections in the history of the United States. Anyone who claims that voting choices don’t matter because all politicians are the same hasn’t been paying attention. The worldviews presented by the two candidates are not just different in terms of policies and promises. As philosophers say, Trump world and Harris world are ontologically different—worlds so different that the inhabitants of each look at the inhabitants of the other not as fellow citizens with whom they disagree profoundly, but rather as aliens from a distant galaxy whose very existence threatens all that is good and holy. For the inhabitants of one of those worlds, once the results of the election are confirmed and made official, “maybe it’s the best thing for you, but it’s the worst that could happen to me” will become their new anthem.

In an interview, philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch once said that one of the best questions a person can ask, either of others or of themselves, is “What are you afraid of?” A companion question is “What’s the worst that could happen?” As noted above, just about every voter could provide a detailed answer to each of these questions today. But step back for a moment. What each of us is really afraid of is that the person we voted for might lose. Simple as that.

Welcome to democracy, people. Sometimes the person you vote for loses. This is my twelfth [now thirteenth] time voting for President—so far, I’m 5 and 6 [now 6 and 6], hoping to be 6 and 6 [now 7-6] this election is called. In other words, if you going to be a participating citizen in a democratic republic such as ours, you’d better get used to losing. Undoubtedly, it feels as if the stakes are much higher than usual in this election, as if all hell will break loose if your candidate doesn’t win. The strange thing, of course, is that in our current polarized world both sides feel this way. But guess what? We’re stuck with each other.

If my candidate wins, then the millions of people who voted for the other guy, people whose sanity and character I have been casting aspersions on in various ways for months on end, are still my fellow citizens—my neighbors, my colleagues at work, and my family members. Whether I like it or not. If my candidate loses (God forbid), then guess what, you millions of people who are celebrating that the worst that could happen happened to me and not to you? I’m still here. I’m not going anywhere. You’re stuck with me as your neighbor, your colleague, your family member. And we all have to deal with each other.

Six times in my life I have voted for a presidential candidate believing that if the other person won, we would be going to hell in a handbasket. Five of those times my candidate lost, and I spent the next four years saying “it can’t possibly ever get any worse than this” (even though it always does).I cast my vote this time with the same energy, convinced that the future of our democracy depends on my candidate winning, more importantly on the other guy losing. But the real work for all of us presents itself daily, not just once every two or four years. We have all painted ourselves so effectively into our respective corners with our fears that the middle of the room, where the work almost always gets done, is largely unoccupied. “The worst that could happen” would be for that to continue, no matter who wins this election.

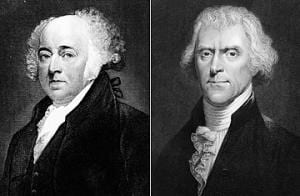

A historian on my campus, a professor emeritus and good friend who was one of my mentors when I first started teaching here more than a quarter-century ago, is a well-published and highly regarded presidential historian. I team-taught with him on a number of occasions over the years. I heard him tell our students on more than one occasion that the American Revolution, despite what the history books tell us, was not completed until the presidential election of 1800, when Thomas Jefferson defeated incumbent President John Adams. Adams and Jefferson were bitter political rivals, polar opposites both in policy commitments and temperament. Each man, as well as their respective party members and those who voted for them, believed that the new republic was in dire danger of failure if the other won.

The election was extraordinarily close, eventually ending up in the House of Representatives. After weeks of shenanigans, political machinations, and dozens of votes, Thomas Jefferson was declared the winner. And then the most remarkable thing happened. The incumbent President, John Adams, handed the reins of power over peacefully to Jefferson, the very man who he was sure would cause the demise of the brand new and fragile republic. Just as the Constitution directed. This, according to my historian friend and colleague, was the true successful conclusion of the American Revolution. Not until a sitting president was willing to hand his power over to a bitter rival, simply because the will of the people and the rule of law said so, was there evidence that this experiment in self-governance might actually work.

We are, arguably, at one of those points in history again. The American experiment is still an experiment; despite close to two-and-a-half centuries of experience behind us, there is no guarantee that it will continue to work going forward. This is why Donald Trump’s refusal to promise a peaceful transition of power if he loses, a refusal undoubtedly supported by many who support him, is so problematic. Part of being a voting American citizen is realizing that we are in it for the long haul, that it is not ultimately about winning or losing any given election, but rather about committing ourselves to the experiment and to each other no matter who wins and who loses.

This whole essay, to be honest, is primarily an attempt to convince myself of what I am writing. It pains me to write this, because there is a significant part of me that really doesn’t want to cooperate or compromise with “the other side.” I’d rather be on the winning side and “stick it to them” in as many ways as my side can figure out until we’re not on the winning side any more. But that isn’t democracy. Democracy thrives only if we work hard to win while recognizing that each of us will take regular turns at being losers. Whether it works or not will depend on what we do next, regardless of how the election turns out.

Note: I obviously had no idea when I wrote this just how relevant my telling the story of the peaceful transition of power in 1800 was to what was to come in the weeks after the 2020 election. I did not know that 1/6/21 was on the horizon. We live in fraught and difficult times–May our fragile experiment in democracy contine.