The last text of the semester in my “Apocalypse” colloquium was Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 post-apocalyptic novel Station Eleven. The apocalypse in question is the “Georgia flu,” a fast-spreading virus that kills over 99% of the human population. The story skips nimbly back and forth between the pre-and post-pandemic world; one of the many fascinating features of the novel is tracking how a person’s seemingly benign attitudes and beliefs take on a life of their own under apocalyptic pressure.

In an early pre-pandemic flashback, we find ourselves at a dinner party thrown by Arthur, a famous actor, and his wife Miranda. Miranda learns indirectly that Arthur is having an affair with Elizabeth, a young woman who is in attendance at the party. Elizabeth has too much to drink and crashes on Arthur and Miranda’s living room couch, where she is confronted by Miranda the following morning. Elizabeth offers a tepid apology, which does not satisfy Miranda.

Miranda: It’s just an awful thing to do.

Elizabeth: I don’t think I’m an awful person.

Miranda: No one ever thinks they’re awful, even people who really are. It’s some sort of survival mechanism.

Elizabeth: I think this is happening because it was supposed to happen.

Miranda: I’d prefer not to think that I’m following a script.

Miranda and Arthur divorce, and Elizabeth becomes Arthur’s second of three wives; she and their son Tyler are both part of the one percent who survive the Georgia flu. Even in the aftermath of the apocalyptic pandemic, Elizabeth maintains her conviction that everything—even apocalyptic pandemics—happens for a reason. When challenged by another survivor to identify “what reason could there possibly be for something like this?”, Elizabeth simply says “everything happens for a reason. It’s not for us to know.”

Elizabeth’s conviction that “everything happens for a reason” is passed on to her son Tyler, with disturbing consequences. As a young boy, after wondering “why did they die instead of us?”, Tyler concludes that “Some people were saved. People like us . . . People who were good, people who weren’t weak.” Far from survivor’s guilt, “everything happens for a reason” convinces Tyler that those who survived the pandemic are special. From there it is only a short step to Tyler as an adult, who tells his community of followers that “I submit that such a perfect agent of death could only be divine . . . The flu was our flood. We were saved because we are the light. We are the pure.”

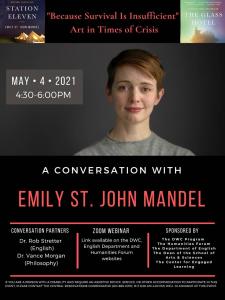

Thanks to the dedicated efforts of my teaching partner, Emily St. John Mandel herself joined our class via Zoom a couple of weeks before the end of the semester. In response to a perceptive student question, the author made it clear that one of the many purposes of her novel is to challenge the familiar trope that “Everything happens for a reason.” “I find that sentiment appalling,” she said in no uncertain terms. “What’s the reason for the Holocaust?”, she asked. Good question. Because those who fall back on “Everything happens for a reason” in difficult circumstances are doing more than simply claiming that effects have causes. They are claiming that there is some sort of cosmic script being played out or divine blueprint being realized that we, mere mortals, are incapable of understanding. As Miranda does, I protest. I prefer to believe that we are not following a script.

In the class before Emily St. John Mandel’s visit, I asked our thirty students on Zoom “How many of you have ever said ‘Everything happens for a reason?’” Well over half of the students raised their hands. When invited to explain why they find this platitude attractive, most students said something along the lines of “it makes me comfortable to believe that even if I don’t understand the reason, there is a larger reason for why even the most horrible things happen.” My forty-something colleague and sixty-something me pushed back, essentially saying to our 18-19 year old students that life isn’t comfortable. If you haven’t discovered that yet, you will. We gave each other a virtual high-five during the next class when the novel’s author agreed strongly with us.

Last summer, I read Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved, a memoir by Kate Bowler, a professor at Duke Divinity School. In her thirties, Bowler is living the life, with her dream job teaching at her alma mater, married to her childhood sweetheart, and the new mother of their first child. And then she is diagnosed with advanced colon cancer, with possibly only months to live. Her book is a brutally honest, sometimes hilarious, sometimes sad, always insightful first-person exploration of faith under pressure. Some of her memoir resonates strongly with what I have learned over the years about lived faith.

After a New York Times op-ed that she wrote about living with cancer and the likelihood of impending death, an essay that served as the basis for her book, Bowler received thousands of emails and pieces of snail mail from well-meaning persons who all believed that they had “the answer” for her struggles, usually accompanied by platitudes such as “everything happens for a reason” and “God is in control.” Many of these “answers” came from assumptions of certainty that Bowler found not only unhelpful, but also inhuman. She writes that “there is a trite cruelty in the logic of the perfectly certain.” That is true about virtually everything we think we know with certainty, particularly about what is greater than us.

Bowler reports that whatever reality God has for her in the midst of pain, suffering, and hope has nothing to do with doctrine, dogma, or certainty. God shows up in the strangest places, such in an inexplicable, almost mystical peace that arrived in the middle of the worst of times. She worries that this abiding peace will not last—and it doesn’t. Yet something remains . . .

There will be no lasting proof that God exists. There will be no formula for how to get it back . . . When the feelings recede like the tide, they will leave an imprint. I would somehow be marked by the presence of an unbidden God.

When asked to provide evidence that God is real, that faith matters, I frequently fall back on the story of the once-blind man in the gospels who is challenged to respond to the charge that the man who healed him is a sinner: “Whether he is a sinner or not, I do not know. But this I do know—I was blind, and now I see.” Faith is radically individual and stubbornly resistant to generalization or formulaic reduction. As Kate Bowler writes,

That is the problem with formulas—they are generic. But there is nothing generic about a human life. There is no life in general. God may be universal, but I am not.