A number of years ago, during a public forum on my campus focused on steps we might take toward addressing the fact that we had a blindingly white student body, faculty, and administration, one of my senior faculty colleagues raised his hand and asked the question that a number of people in the room were probably wondering, but didn’t have the guts to ask: Why do we want to have a diverse campus?

Despite its serious violation of all standards of political correctness, it was a good question, one that bears asking regularly—especially in the middle of nationwide protests and violence rooted in this country’s continuing refusal to address systemic racism, as well as the need to grapple with the challenges of living up to our claimed values of fundamental equality in an increasingly diverse society. So, I return to my colleague’s question: Is diversity truly a fundamentally important value? This question brings me back to a conversation that I imagined a few years ago.

A decade ago, I spent a sabbatical semester at an ecumenical institute on the campus of a Benedictine university in the Midwest. A few of the Benedictines at the abbey on site were liaisons between the abbey and the institute, and were part of our regular lunches and discussions. Wilfred, one of the Benedictines, had recently retired from several decades of teaching physics at the university as well as the prep school nearby. During one lunch conversation Wilfred noted that “Darwin taught us more about God than all of the theologians put together.” I have since taught an honors colloquium in which my students and I discovered just how insightful Wilfred’s comment was.

The colloquium—“Beauty and Violence: The Problem of Natural Evil”—was an exploration of what we might be able to say about what is greater than us through close observation and study of the natural world. My students, the majority of whom are products of a Catholic parochial school education, found on a weekly basis that the God they were taught to believe in simply does not square very well with what we find in front of our faces.

A central part of the course was two weeks with Darwin’s The Origin of Species, one of the most important books ever written in any language or discipline. None of my students, even the two bio majors, had ever read the book—they just had heard a lot about it. I often challenge my students to put persons who supposedly disagree sharply about important matters in conversation with each other.

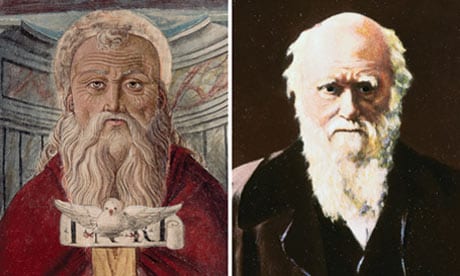

Accordlingly, suppose God and Darwin walk into a bar. The Almighty orders his usual 21-year-old Balvenie neat (it’s an upscale bar), and Charles orders a rum and orange juice (really—he drank that). What might they talk about?

Darwin: I read the other day that between one-third and one-half of the people in the U.S. don’t believe in the theory of evolution. Why do people hate me so much?

God: That’s because they haven’t taken the time to have a drink with you! You have the same public relations problems that I have—people assume things and make judgments about us without ever taking the time to get to know us.

Darwin: I am aware, though, that a lot of good Christians believe that the theory of natural selection, if true, undermines many of the features that Christians traditionally have attributed to you.

God: Like what? I always find it sort of amusing when people get into fights over the details of my personality on the basis of third-hand and partial information.

Darwin: Oh, for instance that you are omnipotent and created the world with a specific plan in mind. Since chance and randomness are central features of natural selection, an all-powerful God who plans all of the details of creation out ahead of time doesn’t fit evolution very well.

God: No kidding! But who ever said that I’m into control and planning in the first place?

Darwin: Uh . . . just about everyone? Put that together with your being all good, as well as omniscient, and the traditional portrait of God Almighty is pretty well filled out.

God: You tell me, Charles. Does that portrait strike you as anything like the person who’s sitting next to you right now?

Darwin: Not everyone gets to have an occasional drink with you like I do. For the most part, the ideas that people have about you are guesswork and projections based on what they have direct access to. Your followers, for instance, have thought for ages that observing the world around us can help us intelligently speculate about what you are like. And the theory of evolution didn’t help.

God: Why not?

Darwin: All I can do is tell you how the theory of natural selection affected my own belief in you over the decades that I was developing the theory. The more I studied the natural world, the more appalled I was by the violence embedded in every part of it, constrasted with the extraordinary beauty and diversity of living things. Then Annie, my eldest and favorite daughter died after a long illness, despite my wife’s and my prayers and the continuing efforts of the best medical people. I tried for many years to square my own experiences and knowledge with what I was supposed to believe about God. An omniscient and omnipotent God who allows pain and suffering to run amok throughout creation? I just could not believe in a God like that anymore.

God: Good, because I don’t believe in that God either. But you’re no atheist. An atheist could not have written your final lines in The Origin of Species: There is grandeur in this view of life . . . having been breathed into a few forms or into one; and whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Darwin: That was inspired, wasn’t it? I think I’m an agnostic. I just don’t know what to think about God. You, I mean. Having a drink with you makes you seem so normal, but as soon as you’re gone I have far more questions than answers.

God: But that’s a good thing. A rabbi I know says that he would rather be on earth with the questions than in heaven with the answers.

Darwin: Really? But what are we supposed to do when what we thought we knew about you just doesn’t fit with what we are learning about ourselves and the world around us?

God: I always say that if you don’t like the answers you are getting to your questions, change the questions! Forget for a minute everything you’ve ever been told about what I’m like and start over. Let’s suppose that your theory of evolution by natural selection is largely correct (it is, by the way). On the basis of what that theory tells you about the world, what might you speculate about me?

Darwin: My first guess is that you like change more than stability, and novelty more than the familiar. Annie Dillard, who is almost as astute an observer of the natural world as I am, wrote that “not only did the creator create everything, but he is apt to create anything. He’ll stop at nothing. There is no one standing over evolution with a blue pencil to say: ‘Now, that one, there, is absolutely ridiculous, and I won’t have it.’” I’d guess you also favor process over finality and imperfection over perfection.

God: And why would I value imperfection over perfection?

Darwin: Because as every artist knows, imperfections are fundamentally necessary to beauty. Charles Baudelaire wrote that “That which is not slightly distorted lacks sensible appeal; from which it follows that irregularity–that is to say, the unexpected, surprise and astonishment, are an essential part and characteristic of beauty.”

God: And Baudelaire was pretty good, wasn’t he? This reminds me of something a physicist-turned-Anglican-priest said recently in an interview: “God is not the puppet master of the universe, pulling every string. God has taken, if you like, a risk. Creation is more like an improvisation than the performance of a fixed score that God wrote in eternity.” John Polkinghorne is right, because I really am more like Ella Fitzgerald than Beethoven.

Darwin: Most importantly, you apparently are committed to freedom and creativity above everything else—not just in human beings, but in everything. Within very broad parameters, life never stops recreating itself in new forms.

God: One of my favorite guys, Teilhard de Chardin (how can you not like a Jesuit paleontologist?), hit the nail on the head when he wrote that “Properly speaking, God does not make: He makes things make themselves.” But, of course, this is risky . . .

Darwin: No kidding! Freedom, open-endedness, radical creativity, a “hands off” attitude—that raises a whole bunch of other questions: the problem of evil, is there a point to all of this, what faith amounts to, can science and religion cooperate . . .

God: Stop! Stop! I’m not sure of the answers to some of those questions myself! (checks his phone)—Shit! Look what time it is! Can you pick up the tab this time, Charles? I forgot my wallet back home . . .

Darwin: Again? Okay, but now you owe me big time . . .

God: In more ways than you know. Wilfred was right. You’ve taught people more about me than all of the theologians put together!