Frank Tupper, an important Baptist theologian who argued that God is in control of very little in our world, died last year. According to an online eulogy and summary of his life, the thesis for Tupper’s writing, theology, and life was that “In every specific historical context with its possibilities and limitations, God always does the most God can do.” As a response to the problem of evil, to pervasive questions about why a good and omnipotent God allows pain, suffering, and evil to exist in our divinely-created world, Tupper’s thesis strikes me as a far better answer than the standard, boilerplate responses that often boil down to platitudes such as “God is in control” or “Everything happens for a reason.” Tupper’s insight is unorthodox and flies in the face of many traditional Christian doctrines, to say the least. That’s probably why I like it so much.

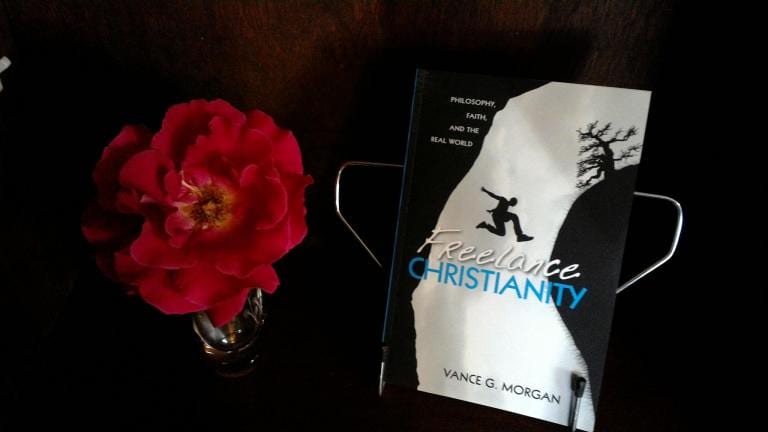

In the eight-plus years that I’ve been writing this blog, I’ve occasionally been asked what a “Freelance Christian” is. I call myself a freelance Christian because I don’t believe that any particular doctrinal formulation of the Christian faith is satisfactory. This is not because I’m still looking for the doctrinal package for Christianity that fits my own eclectic faith most closely; it’s because I don’t believe Christianity can be packaged in a doctrinal statement at all. Jesus did not come to establish a new set of beliefs. Jesus came to show us a new way of life, a new way of being in the world and being with that which is greater than us.

This is why I am relatively comfortable with also describing myself as a “progressive” Christian, since the Christians I know who describe themselves that way tend not to be trying to clean up doctrinal statements. Instead, they seek to discover how the heart of the gospel is relevant to and can be lived out in our contemporary world. Choosing to understand Christianity as something that one lives rather than something that one believes is, of course, problematic for those whose Christianity is more about orthodoxy (what you believe) than about orthopraxy (what you do).

I was asked once a number of years ago when presenting a paper at an ecumenical institute the following question: “Doesn’t a Christian have to believe something with certainty?” My response—“I don’t know . . . do I?”—led to a conversation about how such a cavalier attitude could propel a Christian down the slippery slope to atheism. Or it could, alternatively, open up possible conversations about who or what God is, as well as how God relates to our world and what relationship with God might mean for a human being. Which brings me back to the problem of evil.

As a philosophy professor for the past thirty years and a Christian since around the time I was conceived, I know something about the problem of evil. I have taught two honors courses on it in the past five years and organized a full-semester Early Modern Philosophy course around this problem last fall—a course to be repeated next fall. I was fascinated when I read about Frank Tupper’s perspective on this ubiquitous problem, for a number of reasons, but primarily because it expresses in a striking way the core of what I also have come to think about the relationship of the divine and evil.

Let me put my cards on the table: There is no version of Christianity that “solves” the problem of evil, as if this problem is a logical puzzle or a Rubik’s cube. What Christianity provides is far better than a “solution,” but recognizing this requires a willingness to rethink some doctrinal “givens” and to kick some sacred cows.

The problem of evil is simple to state. It involves four claims that are logically incompatible:

- God is all-good (omnibenevolent)

- God is all-knowing (omniscient)

- God is all-powerful (omnipotent)

- Evil exists

The first three claims are fundamental to traditional theistic belief, while the truth of the fourth claim is self-evident to anyone who listens to the news on a daily basis. Logically, all four claims cannot be true simultaneously. Pick your favorite three to double down on, and the fourth has to be false. Which sucks, because any committed theist who is also an observant human being wants to affirm all four claims.

The problem of evil is no challenge for an atheist, of course, since an atheist denies the truth of all of the first three claims. The theist, Christian or otherwise, who tries to keep all four balls in the air simultaneously will soon find that it cannot be done. Which is not to say, of course, that heroic efforts have not been made to do so. From denying that evil is real to throwing in the towel and saying that the apparent problem is only a result of our limited human knowledge, implying that there is a divine logic in which all of these are compatible, there is no end of efforts to make our favored beliefs and reality hang together.

My own choice is to reject #3 and to say that, for good reasons, God is not omnipotent. Since I believe that God is a God of love, and since I also believe that love and power are incompatible on a deep level, I believe that God chooses to diminish divine power in the interest of lovingly providing human beings with the free choice to return that love (or not), as well as the opportunity to take responsibility for their choices. Once free choice is involved, all bets are off, since there is no guarantee that we will choose wisely, lovingly, or well. Hence evil. But a God who chooses to diminish divine power is not the traditional monotheistic God, as many traditional Christians have been happy to remind me over the years.

Although I only know Frank Tupper’s work through summaries provided by others, he clearly also believed that the creating God chose to limit divine power, instead empowering creation to develop—for better and for worse—freely. In an interview shortly after the publication of his important book, A Scandalous Providence: The Jesus Story of the Compassion of God, Tupper said

I do not believe that God is in control of everything that happens in our world. Indeed, I would argue that God controls very, very little of what happens in our world . . . God chose not to be a do anything, anytime, anywhere kind of God.

Which means that Tupper denied that God is omnipotent. Power and love are incompatible—divine love requires the reduction of divine power and control.

The foundational story of Christianity is a story of diminishment, of weakness, and of overwhelming love. God chooses to address the human condition by becoming human, by embedding divinity in humanity. This is not a “solution” of a “problem”—this is a mystery that transcends doctrinal parsing and logical analysis. Our world is filled with goodness and evil, love and abuse, vulnerability and power, and every other contradiction imaginable.

The heart of Christianity asks us to embrace being the vehicles of the divine in this world and to not be satisfied with or settle for a faith that assures us that it will all work out in the end. There is at least one important truth that Christians and atheists can agree on—human beings are the primary way that goodness gets into a world that is badly in need of light. Acting on that truth does not require any specific doctrinal framework. Rather, it requires the conviction that each person is uniquely qualified and situated to be an instrument of goodness.