Two of the contemporary authors whose insights on faith and spirituality challenge me the most in fruitful ways both have spent years afflicted with cancer. Kate Bowler is an associate professor of the history of Christianity in North America at Duke Divinity School; she burst onto the national scene with her 2018 book Everything Happens for a Reason (and Other Lies I’ve Loved), a memoir that a reviewer calls “A meditation on sense-making when there’s no sense to be made, on letting go when we can’t hold on, and on being unafraid even when we’re terrified.”

Working at her dream job, married to her childhood sweetheart, and the mother of a one-year-old, Kate was diagnosed at age 35 with stage-4 cancer and given no more than a few months to live—Everything Happens is a beautiful and brutally honest account of what followed. Her subsequent books have continued with the same difficult and challenging insights, often delivered with a wicked sense of humor worthy of a stand-up comedian. Her podcast “Everything Happens” is a favorite of mine; the title of her next book, coming out next month, says it all: Have a Beautiful, Terrible Day: Daily Reflections for the Ups, Downs, and In-Betweens. I’ve pre-ordered my copy.

And then there is Christian Wiman, a poet, essayist, memoirist, editor, and critic whose work has simultaneously challenged and attracted me over the last decade. I frequently return to my notes on his 2014 memoir My Bright Abyss at times when my own faith seems dull or stale—he comes from the same religious tradition as I was raised in and often puts his finger on precisely the places where I struggle the most. Here’s a representative insight:

To say that one must live in uncertainty doesn’t begin to get at the tenuous, precarious nature of faith. The minute you begin to speak with certitude about God, he is gone. We praise people for having strong faith, but strength is only one part of that physical metaphor: one also needs flexibility.

Almost two decades ago, just after his 39th birthday and shortly before the birth of his twin daughters, Wiman was diagnosed with a rare, incurable form of blood cancer. His struggles with despair and hope intertwined in the midst of a life painful both physically and spiritually lead him to insights that are uncommon, to say the least. Of his illness, he writes that,

I had—have—cancer. I have been living with it—dying with it—for so long now that it bores me, or baffles me, or drives me into the furthest crannies of literature and theology in search of something that will both speak to and spare my own pain.

Last week’s edition of The New Yorker magazine includes a lengthy article about Wiman called “Close to the Bone.” When I read that Wiman’s new book of poetry/memoir/essay called Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries Against Despair was published at the begi nning of the month, I immediately ordered it from Amazon.

nning of the month, I immediately ordered it from Amazon.

In her review of Zero at the Bone in The New York Times a week ago, Alexandra Jacobs begins by quoting Wiman (who, as you may be gathering, is eminently quotable):

One grows so tired, in American public life of the certitudes and platitudes, the megaphone mouths and stadium praise, influencers and effluencers and the whole tsunami of slop that comes pouring into our lives like toxic sludge.

Amen. Jacobs closes her review by describing the book as “a profane, irreverent, freewheeling and necessary book. Readers of whatever creed will be jolted to lift their heads from their screens and turn them to the unfathomable heavens.”

My copy of Wiman’s newest arrived last Saturday, just in time for Advent beginning the next day. I’ve known for some time that I need to introduce some sort of regular spiritual practice into my daily routine; the New Year’s Day of the liturgical year seemed like a good time to start and Zero to the Bone, with its fifty chapters ranging from two to five pages long that wander through every imaginable genre of writing, struck me as a good framework for daily Advent reading, marking, and inward digestion. If only I can discipline myself to reading no more than two entries per day.

On Sunday I found this on the first page of the first entry. Wiman remembers a question from an atheist several decades ago who, after watching a news report on television about the connections between religion and depression, wondered aloud in Wiman’s company “Why do they believe in something that doesn’t make them happy?” At the time, Wiman writes, he “was an ambivalent atheist” in his twenties, a place I recognize as a space I also occupied in my twenties as I sought to rid myself of some of the toxic aspects of the religion I was raised in. Reflecting on this thirty years later, Wiman observes that,

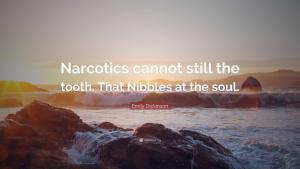

One doesn’t follow God in hope of happiness but because one senses—miserable flimsy little word for that beak in your bowels—a truth that renders ordinary contentment irrelevant . . . The only true antidote to the plague of modern despair is an absolute—and perhaps even annihilating—awe.

This is what Emily Dickinson called “the tooth that nibbles at the soul,” the sense that there is something going on much greater and more important than happiness or comfort. There’s more packed into this passage from the first page of the first entry than I have found in many full books on faith and the real world.

This is what Emily Dickinson called “the tooth that nibbles at the soul,” the sense that there is something going on much greater and more important than happiness or comfort. There’s more packed into this passage from the first page of the first entry than I have found in many full books on faith and the real world.

Just a few pages later, as Wiman reflects on the dynamic of prayer, he wonders about those faithful people who pray for a good parking spot and, when they get one, take it as a sign of the divine’s favor. Rather than ridiculing such folks, as I often do, Wiman suggests this:

Maybe, just maybe, we pray for a parking spot in the faith that there is no permutation of reality too minute or trivial for God to be entirely absent from it.

Why, Wiman then wonders, did Jesus choose “a cheap party trick” of turning water into wine to be his first miracle?

Maybe the lesson we are to learn from this is that we have to turn everything over to God, including those niggling feelings and hesitations we have that the whole rigmarole of sifting scripture like bird’s entrails, and bowing one’s suddenly brainless head, and “believing” in something more than matter—this is all just a little ridiculous, isn’t it?

In her New York Times review, Alexandra Jacobs calls Zero at the Bone “one of those fancy juice cleanses of recent yore, intellectual edition: full of salubrious and often quite tough poetry, philosophy and theology broken down into digestible bits.” The above is a perfect example of what she’s describing.

Advent is a perfect time for such a cleanse, along the lines of what Simone Weil meant when she wrote that “atheism is a purification.” It is worthwhile to occasionally step back and take a new look at what may have become ordinary and stale—faith is no exception. The story Christians tell beginning with Advent takes on new meaning when challenged “at the bone.” For as Teresa of Avila wrote, “God is on the journey too.” I’ll be keeping you updated throughout Advent on how my cleanse is going.