Holy Saturday reminds us that we are mortal and that we all will die. Quoting the Book of Job, the Holy Saturday liturgy reminds us that

[m]ortals die, and are laid low . . . As waters fail from a lake, and a river wastes away and dries up, so mortals lie down and do not rise again; until the heavens are no more, they will not awake or be roused out of their sleep.

Those who loved and followed Jesus, both those who fled and those who stayed, could not have escaped these truths on the day after Jesus was crucified and laid in the tomb. As poet Christian Wiman notes, “resurrection is a fiction and a distraction to anyone who refuses to face the reality of death.” Human beings die and are laid low. And Jesus was a human being.

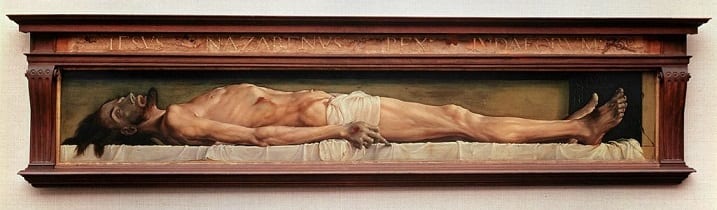

In 1521 the German master Hans Holbein the Younger painted “The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb,” a work that continues to startle and disturb viewers five hundred years later. Emaciated, battered, unflinchingly grotesque, this figure is in the early stages of putrefaction, of rigor mortis, the glassy eyes and mouth open. Three wounds of the Crucifixion are visible: on the side, the effect of a Roman lance, and nail piercings on the feet and on the hand.

Fyodor Dostoevsky viewed the painting in 1867. His reaction was so intense that his wife became concerned. She reported that he turned white and refused to leave. She dragged him away afraid that his heightened emotions might trigger an epileptic episode. He later remarked, “Such a picture might make one lose one’s faith.” A character in Dostoevsky’s 1868 novel The Idiot has the following reaction to a print of Holbein’s painting, undoubtedly reflecting Dostoevsky’s own reaction a year or so earlier:

Supposing that the disciples, the future apostles, the women who had followed Him and stood by the cross, all of whom believed in and worshipped Him—supposing that they saw this tortured body, this face so mangled and bleeding and bruised (and they must have so seen it)—how could they have gazed upon the dreadful sight and yet have believed that He would rise again?

The most likely answer is that they couldn’t. And they didn’t. There is no indication in the Gospels that, despite various things that Jesus had said in the previous months, anyone really believed that he was anything but dead for good.

It is clear throughout his novels that Dostoevsky considered confronting doubts to be a central part of faith. He believed that faith wasn’t bolstered by finding evidence for God, but rather by believing despite the evidence against the story. That helps explain Dostoevsky’s response to Holbein’s painting. The depiction of the dead Christ is so realistic, so jarring, that it is a challenge to one’s faith to continue to believe in the Resurrection. Our eyes and our experience with death tell us that death is final, there can be no reversal of death to life. Mortals die, and are laid low.

The eighteenth-century essayist and philosopher Voltaire once provocatively wrote, “If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.” This statement shook up a number of Voltaire’s contemporaries, leading many to imagine that any person who could write such a thing seriously must be an atheist. The statement remains provocative, and it is clear from his body of work that whatever Voltaire might have been, he was not a traditional religious believer. But with the apparent meaninglessness of human existence and reality in view, Voltaire’s famous claim is absolutely true. The darkest and most sobering parts of human reality cry out for, actually demand, a response. The human epitaph cannot be “Life’s a bitch, and then you die.”

All sorts of responses to whether life has meaning without belief in something greater than us, ranging from religious through philosophical and literary to political, have been offered over the centuries, responses that often conflict with each other and even more frequently fail to take the fundamental problem on squarely. Which of these responses is true? More important, how can we know if any of them are true? How can we be sure that they are anything more than a collection of tunes human beings have written to whistle in the dark until the night overwhelms them?

We cannot be sure. Yet billions of people have been and continue to be willing to shape their lives, to stake their very existence, on the truth of one or more of these stories. Why? Because there is something in the human heart that has to believe them, something that has to hope. And it is that very longing and hope that is perhaps most convincing. As Simone Weil reminds us, “[I]f we ask our Father for bread, he will not give us a stone.”

The third and final portion of George Friedrich Handel’s masterpiece Messiah, immediately following the “Hallelujah Chorus,” begins with “I Know That My Redeemer Liveth,” a soaring, beautiful soprano solo setting of a text from Job, with a concluding sentiment from 1 Corinthians:

I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth;

And though worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God.

For now is Christ risen from the dead, the first fruits of them that sleep.

From the depths of despair, literally from the middle of a pile of ashes, Job clings to a hopeful story, that there is a transcendent and triumphant divine response to human incapacity, despair, and hopelessness. It’s a wonderful story. How can we not believe it?

For reflection: Kathleen Norris writes that “a myth is a story that you know must be true the first time you hear it.” Do the seminal stories of the Christian faith present truths that transcend the facts of what might or might not have actually happened?