It is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for a [non-Christian] to hear a Christian, supposedly giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these [scientific] topics, and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people reveal vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn.

One guess as to who wrote the above. Most likely a progressive Christian denying the authority of the Bible, right? How about this one?

Darwin taught us more about God than all of the theologians put together.

Another liberal progressive who has no respect for traditional Christian belief, without a doubt.

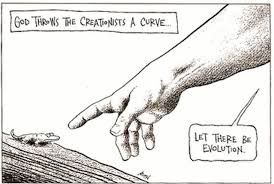

Wrong on both counts, as it turns out. The first, lengthier passage comes from a guy who, 1900 years ago, did more to shape traditional Christian doctrine and attitudes than any single person other than the Apostle Paul. This is from Augustine of Hippo (Catholics like to put “Saint’ in front of his name). Thank you to Pete Enns for reminding me that Augustine wrote this in The Literal Meaning of Genesis; I was reading Enns’ excellent recent book Curve-ball.

The second quote is clearly more contemporary—Augustine had never heard of Darwin nor of his infamous theory of evolution by natural selection. Fifteen years ago I was a “resident scholar” for my spring sabbatical at an ecumenical institute on the campus of St. John’s University in Minnesota, which has a large Benedictine abbey on campus (it was the largest Benedictine monastery in the world for a number of years). Every Monday the eight or nine scholars at the institute for the semester would have lunch with two Benedictines from the Abbey. Kilian was the founder of the institute back in the 1960s; Wilfred was the designated liaison between the Abbey and the institute for that academic year.

I would guess that Wilfred was in his late seventies or early eighties at the time; he had spent his professional career, in addition to being a Benedictine priest, as a high school physics and biology teacher. I don’t exactly remember the context of the Monday lunch conversation in question, but—as I often do—I was attempting to convince some of my reluctant colleagues that Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection was not the uncomfortable challenge to Christian belief that many assumed it was. Wilfred bailed me out by assuring the assembled group that “Darwin has taught us more about God than all of the theologians put together.” Kilian, a world-class theologian in his own right, strongly agreed. Sidebar: Wilfred is now well into his nineties, and Killian is still with us at 103 years old.

I would guess that Wilfred was in his late seventies or early eighties at the time; he had spent his professional career, in addition to being a Benedictine priest, as a high school physics and biology teacher. I don’t exactly remember the context of the Monday lunch conversation in question, but—as I often do—I was attempting to convince some of my reluctant colleagues that Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection was not the uncomfortable challenge to Christian belief that many assumed it was. Wilfred bailed me out by assuring the assembled group that “Darwin has taught us more about God than all of the theologians put together.” Kilian, a world-class theologian in his own right, strongly agreed. Sidebar: Wilfred is now well into his nineties, and Killian is still with us at 103 years old.

I have written about this occasionally on this blog. My post imaging a conversation between Darwin and God over drinks at a bar is one of the top five most read posts in this blog’s dozen-plus year history.

In the spring I will be teaching an honors colloquium called “Beauty and Violence” that I have taught three times before. This colloquium focuses on the problem of natural evil, which briefly stated raises the question of How are we to understand the suffering and pain caused by natural disasters if we simultaneously are committed to believing in a good, all-knowing, and all-powerful God?

It is no surprise that Charles Darwin and his theory of evolution by natural selection are an important centerpiece of this course in its middle weeks. Darwin’s theory landed as a bombshell both in the scientific community and, particularly, in the world of faith and religious belief when it was published in 1859. In “Beauty and Violence” we not only spend time investigating Darwin’s The Origin of Species in detail, but also investigate the ways in which certain strains of Christianity still find it impossible to come to grips with this scientific theory that has, over the past century and a half, become established as foundational in science. For instance, we spend a class considering a 2007 documentary that provides an account of the 2004 trial in Dover, Pennsylvania in which the Dover school board’s mandate that intelligent design be taught alongside Darwin as an alternative scientific account of evolution was ruled a violation of the separation of religion and state.

In that colloquium we also spend time with Jesuit theologian and biologist Teilhard de Chardin who memorably said that “God does not make: He makes things make themselves,” as well as Anglican priest and well-known physicist John Polkinghorne who argues that

God is not the puppet master of the universe, pulling every string. God has taken, if you like, a risk. Creation is more like an improvisation than the performance of a fixed score that God wrote in eternity.

Pete Enns puts it succinctly in Curve-ball: “Evolution is God’s way of creating.”

But my favorite reflection on the power and mystery of evolution, as well as its possibly religious implications, comes from the man himself at the end of The Origin of Species.

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Darwin himself worried about the religious implications of his theory and hesitated to publish it for years partially because of how disruptive it would be to his wife’s traditional Christian faith. Darwin’s own faith “evolved” greatly over his lifetime, and he knew by the end of his life that he could no longer believe in the traditional God he had believed in earlier in his life.

And, might I suggest, neither should we. The theory of evolution raises serious challenges to traditional conceptions, without a doubt. But why should we believe that faith should avoid a continuing engagement with evolving and growing human experience and knowledge? Believing in a God who creates through evolution and who inhabits every bit of creation makes it far more difficult, for instance, to believe that human beings are radically separate from creation or that we are “special” in the ways that we so often insist on believing that we are. It makes it much more difficult to ignore the devastation that human beings wreak on our planet that God created.

These are all good things. And, returning to the quote from John Polkinghorne above, a God who is more like Ella Fitzgerald or Louis Armstrong than like Ludwig van Beethoven or Gustav Mahler is a much more interesting God.