What is bothering me incessantly is the question of what Christianity really is, or indeed who Christ really is, for us today. The time when people could be told everything by means of words, whether theological or pious, is over—and that means the time of religion in general. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters from Prison

What is bothering me incessantly is the question of what Christianity really is, or indeed who Christ really is, for us today. The time when people could be told everything by means of words, whether theological or pious, is over—and that means the time of religion in general. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters from Prison

A few years ago, after a week at work that completely wore me out, I was strongly tempted to skip church on Sunday morning for the first time in months. But it was Palm Sunday, Jeanne was scheduled to be chalice bearer at the altar, so my Protestant guilt kicked in and off to church I went. At least it was going to be the first Sunday service in weeks in which I had nothing to do but sit in the pew—no seminar to lead, no scripture to read, and no organ to play.  I would try to enjoy the dramatic reading of the Passion narrative that is always part of the Palm Sunday service before returning home to finish our taxes. What fun.

I would try to enjoy the dramatic reading of the Passion narrative that is always part of the Palm Sunday service before returning home to finish our taxes. What fun.

As I entered the back of the church, our rector and my good friend Marsue was looking dramatic in her chasuble, appropriately red for Palm Sunday, as she waited to process to the front with the servers, readers, and choir. Motioning me over, she whispered “do you want to read?” “Not really,” I thought as I looked to see what roles for the upcoming Passion reading were still available. Just about all of them, as it turned out, including the role of Jesus. “I’ll be Jesus,” I sighed. “I’ve never gotten to read his part.”

“I’ll be Jesus.” That’s really what it boils down to for those of us who have signed on to the project of trying to live out a serious Christian faith commitment. Holy Week is a time that many try to virtually “walk in the steps of Jesus” liturgically in the various special services during the week. But to actually be God in the world, to be the vehicle through which the divine makes contact with our human reality—that’s nuts. No wonder we are so creative in finding ways to make the demands of the life of faith more manageable. But my own attempts to avoid the challenges of what I claim to take seriously are regularly exposed by the prison letters of twentieth-century Lutheran pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

In the months between his imprisonment and his execution by the Nazis, Bonhoeffer wrote dozens of letters to his best friend Eberhard Bethge, letters in which he explored and pressed the boundaries of his Christian faith, a faith for which he would eventually die, in ways that have challenged and shocked readers ever since. Facing imminent death has a tendency to focus one’s attention and to clearly reveal what is important and what isn’t. As Bonhoeffer asks, “What do we really believe? I mean, believe in such a way that we stake our lives on it?” These letters, with which I spent some time a few weeks ago with some sophomores in my “Faith and Doubt” colloquium, are causing me to think about and look at the Holy Week narrative very differently.

In the months between his imprisonment and his execution by the Nazis, Bonhoeffer wrote dozens of letters to his best friend Eberhard Bethge, letters in which he explored and pressed the boundaries of his Christian faith, a faith for which he would eventually die, in ways that have challenged and shocked readers ever since. Facing imminent death has a tendency to focus one’s attention and to clearly reveal what is important and what isn’t. As Bonhoeffer asks, “What do we really believe? I mean, believe in such a way that we stake our lives on it?” These letters, with which I spent some time a few weeks ago with some sophomores in my “Faith and Doubt” colloquium, are causing me to think about and look at the Holy Week narrative very differently.

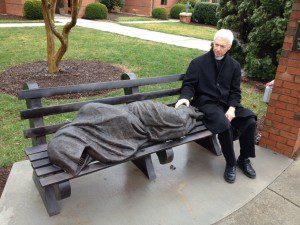

Underlying the liturgies and activities between Palm Sunday and Easter is a shocking story in which “God lets the divine self be pushed out of the world onto the cross.” God is apparently either unwilling or unable to engage with the suffering and pain of the world other than to become part of it. If the dramatic events of Jesus’ final days are models for our lives in a suffering and distressed world, it is clear that “Christ helps us, not by virtue of his omnipotence, but by virtue of his weakness and suffering.”

I remember a rather dramatic solo that my aunt used to sing in the church of my youth almost every year at some point leading up to Good Friday that includes the line “he could have called ten thousand angels, but he died alone for you and me.” If we take all of the accretions of dogma and doctrine out of the picture, the story of Jesus’ last days is a disaster—as I read that Palm Sunday morning during the Passion narrative as Matthew presents it, the final words Jesus gasps from the cross are “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Precisely the question Bonhoeffer must have been asking from his prison cell.

I’ll be wrestling with some of this here this week; at the moment, I’m focused on the following from one of Bonhoeffer’s last letters:

To be a Christian does not mean to be religious in a particular way, to make something of oneself . . . but to be a person—not a type of person, but the person that Christ creates in us. It is not the religious act that makes the Christian, but participation in the sufferings of God in the secular life.

How to do that? That is the question. See you in a couple days when Jesus kills a fig tree.