Today is my youngest son’s 42nd birthday–which makes me feel exceptionally old! I always tell people that I was in my early teens when my sons were born. But enough about me–those who know Justin know what a stellar human being he is, a great friend, a compassionate and dedicated professional (a crises co-responder who literally saves lives on a weekly basis), and a wonderful son.

We will be joining him, along with his older brother Caleb and our daughter-in-law Alisha, in Arizona at my brother’s house for Christmas. For Thanksgiving, I’m sure he’ll be spending time with his wonderful circle of friends in Colorado as he prepares to cheer his beloved Ohio State Buckeyes on to victory over the hated Michigan Wolverines on Saturday.

Please indulge me as I repeat an essay I wrote about Justin a number of years ago–it will provide you with some details about why his birthday is worth celebrating. Happy birthday, dude!

Unlike many academics, I greatly enjoy commencement exercises. After experiencing three of my own (BA, MA, and PhD) spread over thirteen years, I have participated in twenty-one such ceremonies at various ranks of professorship, every year since 1992 with the exception of three missed during sabbatical semesters. Generally at least two-and-a-half hours in length, adding extra half hours depending on how many honorary degrees are conferred and the length of the keynote address, most academics place commencement on the same level of enjoyment and interest as sticking a fork in one’s eye. I look at it differently.

First of all, very few people get to participate in them regularly, so my access marks me as somewhat special. Second, I enjoy seeing if I can pick out the two or three dozen of my students from as long as three years past from the hundreds of diploma receivers as they maneuver in assembly line fashion across the stage. But most of all, I like the liturgical elements—funny clothes, unusual conferral sentences said “just so,” processing, recessing, music only heard at commencements, rituals performed only once per year—it’s just like being in church, but it isn’t. I make no secret of my attraction to liturgy, the primary reason I felt at home when first attending Episcopal services thirty years ago, and it doesn’t matter much to me whether the liturgy is secular or sacred. Liturgy is liturgy—it’s an opportunity for grown up human beings to behave strangely and ritualistically on a regular basis.

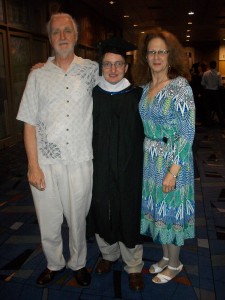

For the most part commencement ceremonies blend into each other very quickly;  only those with the rare interesting keynote addresses stand out. In the past decade or so at my college these have included Tim Russert, Richard Daley Jr., and (this year) Temple Grandin. But last Friday I attended a commencement ceremony that I will never forget, one that will perhaps be more memorable going forward than even those at which I received my own degrees. Last Sunday was the day that Pooker received his Master’s degree.

only those with the rare interesting keynote addresses stand out. In the past decade or so at my college these have included Tim Russert, Richard Daley Jr., and (this year) Temple Grandin. But last Friday I attended a commencement ceremony that I will never forget, one that will perhaps be more memorable going forward than even those at which I received my own degrees. Last Sunday was the day that Pooker received his Master’s degree.

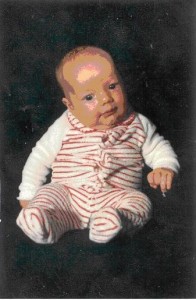

“POOKER???” you ask—yes. Pooker. My youngest son Justin is one of those unfortunate persons whose childhood nickname has stuck into adulthood, at least with his immediate family. As a baby, Justin’s face was as round as Charlie Brown’s, but his nickname comes from another cartoon character with a round head—Garfield’s teddy bear “Pooky.” This quickly morphed into “Pooker,” and there it is. He’s very good-natured about it—to a point. He’ll probably slap me upside the head when he finds out that I have outed his nickname on my blog.

“POOKER???” you ask—yes. Pooker. My youngest son Justin is one of those unfortunate persons whose childhood nickname has stuck into adulthood, at least with his immediate family. As a baby, Justin’s face was as round as Charlie Brown’s, but his nickname comes from another cartoon character with a round head—Garfield’s teddy bear “Pooky.” This quickly morphed into “Pooker,” and there it is. He’s very good-natured about it—to a point. He’ll probably slap me upside the head when he finds out that I have outed his nickname on my blog.

Justin was the cutest kid in any crowd when young, every teacher’s pet and every adult’s favorite. I treated him and talked to him as if he was a very short adult, as I did his older brother (I called them “the midgets”), so Justin was always more comfortable with adults than with his peers. He was the sort of kid that one could imagine living a charmed life with all sorts of waters parting before him and unicorns farting rainbows in his wake.

But I remember clearly the day that this perception ended for me. During his yearly physical when in eighth grade his pediatrician called me into the examination room and asked Justin to bend over and touch his toes. “See that?” the doctor asked as he pointed at my son’s back. Rather than a straight line, his spine was tracing an odd backwards “S”—the clear signs of rapidly developing scoliosis. After several months of unsuccessful exercises and therapies, two titanium rods were inserted in his back during a twelve-hour surgery, guaranteeing that he would set off security alarms at every airport after 9/11 several years later. Justin’s natural patience, resilience, stubbornness, humor and good will were sorely tested and sharply honed during these months, preparing him for  challenges and obstacles even more daunting to come.

challenges and obstacles even more daunting to come.

As Justin moved through adolescence and into early adulthood, he evolved into a unique human being (don’t we all?). We have always been very close (he has accused me of being his soul mate). He has my sarcastic and irreverent sense of humor and left political leanings, but an empathy and sensitivity for the needs of others that I largely lack.  He has a quirky but deep spirituality, hardly a surprise after more than two decades of hanging around a stepmother and father whose spiritual journeys have been just as quirky and meaningful.

He has a quirky but deep spirituality, hardly a surprise after more than two decades of hanging around a stepmother and father whose spiritual journeys have been just as quirky and meaningful.

School was more challenging as he progressed into high school, yet he can quote lengthy dialogs verbatim from movies, television shows and conversations without breaking a sweat. After graduating high school he went to college in northwestern Ohio at a school with a well-regarded pre-veterinary program; Justin had been aiming for a career in veterinary medicine for years. But as he proceeded to veterinary studies after earning his Bachelor of Science, the wheels began to slowly fall off in various sorts of ways.

In no particular order, a series of girlfriends ranging from “nice enough girl, but not right for Justin” to “total lunatic, not right for anyone.” A succession of professors who refused to round a grade up the half point necessary to keep Justin academically viable. Taking a crucial early semester off from veterinary school in the Caribbean to be with and take care of his girlfriend in Ohio who had been diagnosed with cancer (she is now cancer free), then never being able to catch up and failing out. Being diagnosed as ADHD in his middle twenties (something it would have been great to know many years earlier—it would have helped explain a lot). Many series of tests and many sessions of therapy. Being diagnosed with cancer himself a couple of years later and enduring surgery then many months of radiation and treatment (he is now cancer free). More academic attempts and failures, all the time living back with his parents at a time in life when most young men are developing lives of independence and working in slightly more than minimum wage jobs. Nothing came easy anymore; Murphy’s Law seemed to have found a home in Justin.

There were times when I wondered whether Justin was not meant to be in higher education, thinking he might do better or be happier simply settling into a job somewhere, dropping his professional hopes and dreams, and climbing the career ladder, even though I am Mr. Higher Education personified. But here I turned out to be my own worst enemy. Justin was six years old when I entered my PhD program and grew up watching me grow into a teaching career that has been so fulfilling and such a perfect fit that I call it a vocation or calling rather than a job.  That became his own life goal—to find his passion, his calling just as I had found mine. His stubbornness and tenacity guaranteed that he would endure multiple roadblocks, hurdles and failures in his pursuit of his passion, even if he didn’t know what it was, and would refuse to settle for anything less.

That became his own life goal—to find his passion, his calling just as I had found mine. His stubbornness and tenacity guaranteed that he would endure multiple roadblocks, hurdles and failures in his pursuit of his passion, even if he didn’t know what it was, and would refuse to settle for anything less.

His passion was slowly revealed through several exploratory online courses, eventually focused on a Master’s in Psychology. I confess that I had my private doubts, given my old-school educator’s suspicions about online classes and a few unsuccessful similar attempts in Justin’s past. But as he passed course after course, negotiating the sorts of hurdles that would have derailed him in previous years, the light at the end of the tunnel became brighter. His innate sensitivity to the needs of others, along with his longstanding love of horses, directed him toward an ultimate goal of Equine Assisted Therapy in which horses are used as facilitators of change and healing. He didn’t get his equine attraction from me, by the way—they scare the shit out of me.

But although one can lie to a therapist, one apparently cannot lie to a horse. Who knew that Wilbur’s regular conversations with Mister Ed were actually therapy? And what person in need of equine therapy will be able to resist the spectacular tattoo of Secretariat on the back of Justin’s left calf, courtesy of his tattoo artist brother Caleb?![7691_10202631908378365_1261596618_n[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2014/07/7691_10202631908378365_1261596618_n1-168x300.jpg) When the Dean of Students conferred collective degrees on several hundred MA and PhD graduates last Sunday, I finally believed it—a leg of Justin’s journey that many times had seemed impossible and impractical had been completed. With flying colors.

When the Dean of Students conferred collective degrees on several hundred MA and PhD graduates last Sunday, I finally believed it—a leg of Justin’s journey that many times had seemed impossible and impractical had been completed. With flying colors.

It is difficult to step back from the day-to-day struggles that Jeanne and I have lived over the last several years with Justin to truly put his accomplishments in perspective, but I know that I have never encountered a student in twenty-five plus years of teaching who deserves their degree more than Justin does. Tenacity, faith, commitment, stubbornness, humor and love in equal parts—these form the foundation of Pooker the man. In Ancient Rome, the dictator’s right-hand man was called the Master of the Horse. Mark Antony was Julius Caesar’s Master of the Horse—his confidant, critic, conscience, problem solver, hit man and most dependable friend. These are all qualities that the newest Horse Master possesses in excess. Any smart dictator would be as proud to bring him into the inner circle as I am proud that he is my son. But he would look awful in a toga.