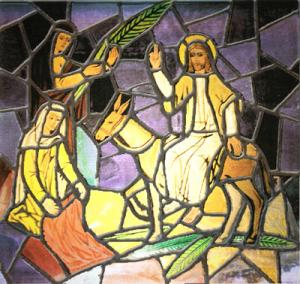

The Palm Sunday celebration in a liturgical Christian church can be both confusing and jarring. Everyone with a religious molecule in their bodies knows that Palm Sunday is about Jesus riding triumphantly into Jerusalem on a donkey (or colt), but this gets only about fifteen minutes of airtime in the Palm Sunday liturgy. The priest reads the Palm Sunday gospel, the ushers distribute palms while everyone sings “All Glory, Laud and Honor” or something similar, the Old Testament reading, Psalm, and New Testament readings for the day are delivered, and then the liturgical transmission shifts from fifth to second gear without a clutch. Various assigned participants read the Passion story from the gospel du jour, and the joy of Jesus’ triumphant entry transitions into the drama and tragedy of the Passion, ending with Joseph of Arimathea providing a tomb for Jesus’ body.

A few years ago, after a week at work that completely wore me out, I was strongly tempted to skip church on Sunday morning for the first time in months. But it was Palm Sunday, Jeanne was scheduled to be chalice bearer at the altar, so my Protestant guilt kicked in and off to church I went. At least it was going to be the first Sunday service in weeks in which I had nothing to do but sit in the pew—no seminar to lead, no scripture to read, and no organ to play. I would try to enjoy the dramatic reading of the Passion narrative that is always part of the Palm Sunday service before returning home to finish our taxes. What fun.

As I entered the back of the church, Marsue was looking dramatic in her chasuble, appropriately red for Palm Sunday, as she waited to process to the front with the servers, readers, and choir. Motioning me over, she whispered “do you want to read?” “Not really,” I thought as I looked to see what roles for the upcoming Passion reading were still available. Just about all of them, as it turned out, including the role of Jesus. “I’ll be Jesus,” I sighed. “I’ve never gotten to read his part.”

“I’ll be Jesus.” That’s really what it boils down to for those of us who have signed on to the project of trying to live out a serious Christian faith commitment. Holy Week is a time that many try to virtually “walk in the steps of Jesus” liturgically in the various special services during the week. But to actually be God in the world, to be the vehicle through which the divine makes contact with our human reality—that’s crazy. No wonder we are so creative in finding ways to make the demands of the life of faith more manageable. But my own attempts to avoid the challenges of what I claim to take seriously are regularly exposed by the prison letters of twentieth-century Lutheran pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

In the months between his imprisonment and his execution by the Nazis, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote dozens of letters to his best friend Eberhard Bethge, letters in which he explored and pressed the boundaries of his Christian faith for which he would eventually die, in ways that have challenged and shocked readers ever since. Facing imminent death has a tendency to focus one’s attention and to clearly reveal what is important and what isn’t. As Bonhoeffer asks, “What do we really believe? I mean, believe in such a way that we stake our lives on it?” These letters cause me to think about and look at the Holy Week narrative very differently.

Underlying the liturgies and activities between Palm Sunday and Easter is a shocking story in which “God lets the divine self be pushed out of the world onto the cross.” God is apparently either unwilling or unable to engage with the suffering and pain of the world other than to become part of it. If the dramatic events of Jesus’ final days are models for our lives in a suffering and distressed world, it is clear that “Christ helps us, not by virtue of his omnipotence, but by virtue of his weakness and suffering.”

I remember a rather dramatic solo that my aunt used to sing in the church of my youth almost every year at some point leading up to Easter that includes the line “he could have called ten thousand angels, but he died alone for you and me.” If we take all of the accretions of dogma and doctrine out of the picture, the story of Jesus’ last days is a disaster—as I read that Palm Sunday morning during the Passion narrative as Matthew presents it, the final words Jesus gasps from the cross are “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Precisely the question Bonhoeffer must have been asking from his prison cell.

To be a Christian does not mean to be religious in a particular way, to make something of oneself . . . but to be a person—not a type of person, but the person that Christ creates in us. It is not the religious act that makes the Christian, but participation in the sufferings of God in the secular life.

As you live out Holy Week this year, ask yourself: Who is the person who Christ is creating in me? How do I bring that person out of the guardrails of the liturgy and into the world?