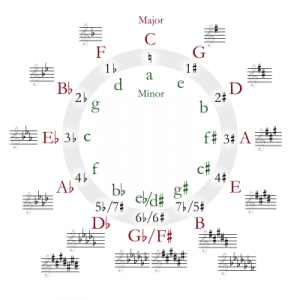

At some point early in their musical training, all serious musicians are introduced to the “circle of fifths,” a handy chart that maps out the complicated but fascinating relationships among the twelve tones of the chromatic scale, their corresponding key signatures, as well as the associations between the major and minor keys.  I was fortunate to have Katrina Munn, a graduate of Julliard, as my piano teacher from age four to eleven—she was a stickler for theory and precision and had a large poster of the circle of fifths on the wall of her studio. I was immediately fascinated—it looked like a labyrinth or something out of The Lord of the Rings, and as I was gradually introduced to the twelve major keys, the twelve related minors, and their harmonic relationships I was able to trace geometrically on the chart the harmonies I had been hearing in my head for as long as I could remember.

I was fortunate to have Katrina Munn, a graduate of Julliard, as my piano teacher from age four to eleven—she was a stickler for theory and precision and had a large poster of the circle of fifths on the wall of her studio. I was immediately fascinated—it looked like a labyrinth or something out of The Lord of the Rings, and as I was gradually introduced to the twelve major keys, the twelve related minors, and their harmonic relationships I was able to trace geometrically on the chart the harmonies I had been hearing in my head for as long as I could remember.

Recently the following from Richard Powers’ Orfeo got me to thinking about the major and minor keys in a new way.

There’s joy in a minor key, a deep pleasure to be had from hearing the darkest tune and discovering you’re equal to it.

A lot can be learned from the major and minor keys that is applicable to everyday life. Traditionally the major keys have been described as “bright, extroverted, upbeat” and so on, while the minor keys are “introspective, complex, sad” or even “depressing.” Yet the circle of fifths shows that each major has its relative minor that is only one note different—a note that makes all the difference. Powers, who is a classically trained musician, is noting something important about the minor keys—they are rich and evocative in ways with which the brighter and more popular majors cannot compete. Yet the dividing line between major and minor is razor thin—if we are to pay proper attention to the music of our lives, understanding how major and minor interweave is crucial.

I had the opportunity to explore this with “Living Stones,” the adult Christian education group that I lead after church once a month, one Sunday a couple of summers ago after the morning service. I was doing double duty, as I was also organist that morning, alternating with the organist emeritus every other week through the summer as the church was searching for a new full-time music minister. The fifteen or so regulars have a wide range of experience with music (or lack of same), so I presumed no prior knowledge. Gathering in the choir stalls by the organ rather than in our usual location,

I oriented them to the major/minor distinction by suggesting that in the cycle of liturgical seasons, Easter and Christmas are major key seasons while Advent and Lent are minor key seasons. We moved then to a listening exercise, as I played first “My Country ‘Tis of Thee,” our closing hymn for the morning because of it being July 4th Sunday, in F minor rather than its original F major, then a representative minor key hymn, “If Thou But Trust in God to Guide Thee,” in G major rather than its original G minor. As the Living Stoners compared the new keys to the hymn texts, they agreed that major is appropriate for the first hymn than minor and minor more appropriate to the second than major. Different texts require different tunes—and so it goes with the chapters and texts of our lives.

The Book of Job from the Hebrew Scriptures is a case in point. The story is familiar. Job, “a man blameless and upright . . . who feared God and shunned evil,” is the topic of conversation between God and Satan, “the accuser.” In response to God’s “Have you considered my servant Job? There is none like him on the earth,” Satan replies “Well duh! You give him everything he wants and you have built a protective hedge around him.” After God agrees to remove the hedge at Satan’s suggestion just to see what happens, Job’s flocks, crops, servants and children are swept away within six short verses and one of the greatest texts on the dynamic of suffering is underway.

The drama of Job is relentless, with his suffering unaddressed by his apparently well-meaning friends and his less than supportive wife. Underlying it all is Job’s insistence that his suffering and pain is not justified in any sense that he (or any other human being) can understand. It is clear that he will not “curse God and die,” as his wife advises him to do—his commitment to his God is unshakable. “Though he slay me, yet I will trust him.”

Job’s commitment, however, is neither passive nor facile. He wants answers and challenges a silent God to provide them. With very few exceptions, the Book of Job is entirely written in a minor key; the message of Job is that sometimes minor keys do not get resolved into major keys. Sometimes the text of one’s life demands a minor key; simply “waiting it out” or longing for it to be something it is not is to rob oneself of the richness and depth that only minor harmonies can provide.

When God finally does respond to Job’s questions and challenges, it is in a way that on the surface, at least, is entirely unsatisfactory to our contemporary sense of fairness and justice. God does not provide any reasons for Job’s misfortunes, nor does God explain himself. Rather, God makes clear in a lengthy soliloquy that he does not have to explain himself at all. As Admiral James Stockdale once described God’s response to Job, “I’m God and you’re not. This is my world—either deal with it or get out.”

It’s a tough message for our modern sensibilities, but is far closer to the reality of the world we find ourselves in than the stories we tell ourselves about “things working out in the end” or “justice will prevail.” Whatever value there is in suffering cannot lie in hopes for its removal or resolution. Yet we continue to try. There is nothing hokier or more forced than to resolve a composition from a minor key to its accompanying major in the last measure of the piece.

But this is precisely what we find at the end of Job. In the final verses of the last chapter, after Job has been subdued by the divine display of power and superiority, Job magically gets everything back—children, flocks, servants, lands—and even his useless “comforters” and unhelpful wife get told off by God. “And they lived happily ever after,” in other words. I learned from one of my theology colleagues a number of years ago that these closing verses are not in the oldest texts of Job, but were apparently added in several decades or even centuries later.

Why? I asked my group. Why would someone want to change the original minor key story of Job, resolving it to a major key in the last measure? “Because the original ending is too tough,” someone suggested. “Because people want to believe that the suffering has a point, that it is all for something,” another thought. Which makes the better story? The original or the one with the new ending? “The original is truer,” an eighty-something Living Stoner said. “People don’t come back. Things that you lose don’t return.”

And she was right. If there is meaning in the minor key movements of my life’s symphony, it has to be in the movement, not because the final movement will return to a joyful major key. The major keys ride the waves, but the minor keys plumb the depths, depths that give a life its richness and texture. As Richard Powers suggests, there is joy and satisfaction to be found in the midst of the suffering, a joy that is largely unavailable in any other context.

A few years ago, MSNBC (the only 24-7 news channel I can stomach, and even that not for very long) had a new ad campaign: Lean Forward. Out of context, it made little sense. Lean forward to what? But in the minor keys of our lives, “lean forward” or “lean in” is far better advice than “hold your breath and wait it out.” The purpose of the minor keys is not to provide a temporary alternative to majors. Rather, as another ad campaign many years ago suggested, sometimes minor harmonies are the most important threads in “the fabric of our lives.”