Your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions.

This, promises the obscure prophet Joel in the Hebrew Scriptures, will be one of the signs that God has “poured out [his] Spirit upon all flesh.” Exactly what I would expect a prophet to say. Unsaid, however, is that in the meantime “your old women, your young women, and your middle-aged men and women will roll up their sleeves and get shit done.” The tension between visionaries and realists, between dreamers and pragmatists, is a healthy part of the human condition—but only when each side recognizes the equal importance and necessity of the other side.

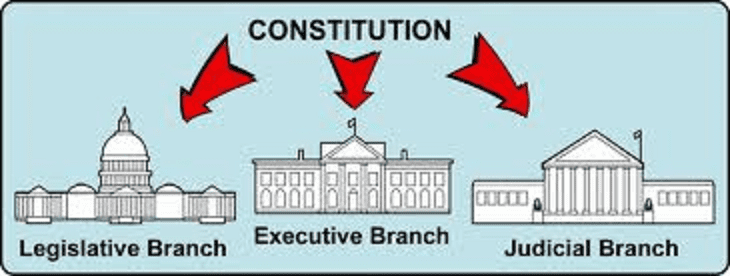

Some people confuse the dreamer/pragmatist difference with the difference between optimists and pessimists; these two distinctions are not the same. I, as an optimist and a pragmatist, am a case in point. I find that a closer parallel to the dreamer/pragmatist distinction more closely parallels the differences between the three branches of government that we learned about in fifth grade civics lessons. The energies that drive the dreamer or visionary differ from those of the pragmatist in the same ways that legislative energies are different from those of the executive.

Not particularly being a political animal, I did not know about these crucial differences until core curriculum review began on our campus over a decade ago. Although I participated in many focus groups and debated endlessly on line with my colleagues about the true purposes and value of a liberal arts education, I had no desire to part of the Faculty Senate legislative process that hammered out a new core curriculum that was finally approved by the college president. Legislators, in spite of appearances, primarily are dreamers and visionaries—persons who imagine what a better future might look like and how it might possibly best be organized, then turn the vision over to executive pragmatists to transform this vision into “boots on the ground” reality.

I am by nature one of those pragmatists and, after the new core curriculum was instated, spent the next four years leading the attempt to make a reality the central portion of the new core curriculum fashioned by the legislators, a revitalized and freshly imagined version of the large interdisciplinary program that has been the centerpiece of my college’s core curriculum for more than four decades. The new program is not exactly the one I would have invented had it been up to me (it isn’t a radical enough change), but as a pragmatist and executive the question was no longer “What program would I (we) have invented had it been entirely up to me (us)?” or even “Do I think this new program is a good idea?” Both of these questions were irrelevant—the horse was now out of the barn. The important question was “How are we going to make this visionary product happen?”

I recall an interesting conversation that I had while I directed the program with a faculty member teaching in the program who also happened to have been his department’s senator during the Faculty Senate’s shaping of the new core. My colleague was not entirely in agreement with some of the new policies being developed as the new program went into real-time reality. “Vance,” he said, “These new policies don’t really reflect the vision of those who were debating the legislation a couple of years ago.” “I don’t care, Jack,” I replied (his name has been changed even though he needs no protection and is anything but innocent). “It’s one thing to plan something—it’s another thing entirely to make it happen.” Yet Jack and I are good friends, just as dreamers and pragmatists should be (hear that, politicians in Washington?).

In Genesis, we find the story of a classic dreamer/pragmatist clash that generated a great deal of conflict. Genesis is full of great stories, including the story of Jacob, Abraham’s grandson and probably my favorite character in the Bible. Smart, manipulative, younger brother, momma’s boy, God-obsessed, believer in love at first sight—I find a lot of myself in Jacob.

But then we move to “Jacob—the Next Generation” and are introduced to one of my least favorite guys in the Bible—Joseph. Joseph is son number eleven of Jacob’s twelve sons fathered by his two wives and two concubines (at least those are all Genesis tells us about). But he is the first son of Jacob’s favorite wife, Rachel, so it’s not surprising that as the first child of the love of Jacob’s life, Joseph is the favored son of the twelve. The subtext just below the surface of the Genesis account is that Joseph is a spoiled brat. He gets the best clothes, he doesn’t have to work in the fields doing farmer and shepherd stuff as his ten older brothers do, he probably hasn’t done a day of real work in his life—in his father’s eyes, he can do no wrong. And he knows this, playing the superior, “special case” card with his older brothers every chance he gets. Furthermore, he has weird dreams that he interprets to support his general conviction that he is superior to his brothers in every way.

Jacob, who for a smart guy is remarkably clueless about family dynamics, sends Joseph off on his own to check up and report on his older brothers who are tending the family flocks some distance away and report back to home base. Upon seeing their “special case” brother approaching without Dad’s protection, the older brothers see an opportunity—“this time we’re going to get this little bastard.”

And they do, first throwing him into a deep pit where they plan to abandon him, them deciding instead to sell him as a slave to a caravan of Ishmaelite merchants on their way to Egypt. This is just the beginning of Joseph’s story, carried on through the remaining twelve chapters of Genesis, but as horrific the beginning of the story is, the energies are very human and familiar. Those of you with a brother and sister, be honest. Haven’t there been times in your life when you would have loved to abandon your sibling in a pit?

When the brothers see Joseph approaching, they don’t say “Here comes the spoiled brat,” “Here comes the special case,” or even “Here comes that little jerk Joseph spying on us.” Instead they say “Here comes this dreamer.” As they plot throwing him into a pit, they say “We shall see what will become of his dreams!” In other words, “Let’s see how visioning visions, dreaming dreams and thinking great thoughts helps you at the bottom of this pit, little brother!”

Underlying the horribly dysfunctional sibling dynamics in Jacob’s family is a classic case of dreamer vs. pragmatist. When push comes to shove, as it always does, the pragmatist wants to know just how the ethereal perspective of the visionary or dreamer is going to put food on the table, while the dreamer reminds us that, as the author of Proverbs notes, “where there is no vision the people perish.”

As the story unfolds, Joseph will learn how to turn his visionary abilities into a practical commodity, first saving himself from execution then saving his adopted country from famine and starvation. His strong intuitive abilities will manufacture a family reunion that is both just payback and unconditionally loving. His journey from “out there” dreamer to integrated human being is a long one, just as it is for all of us regardless of which direction we are journeying from. Just as the dreamer needs to get her head out of the clouds occasionally and find something to eat, so the pragmatist needs to lift his nose from the grindstone often enough to remember that without regular dream infusions, getting shit done will be just that.

PS: My new book, Prayer for People Who Don’t Believe in God, was released by Wood Lake Publishing on October 1! To get a description of the book, some endorsements, and information on ordering it, go to the “Books by this Author” location in the right hand column on this page, or click here: http://bit.ly/prayer4people