The drama from Thursday into early Friday of Holy Week is both familiar and inescapable. The Last Supper. The Garden of Gethsemane. Judas’s betrayal. Peter’s denial. All inexorably leading to trial, conviction, and crucifixion. The elements of the story are so familiar to Christians and others that it is tempting to suppose that there are no more fresh takes or new perspectives to consider on this important but well-worn story.

The lectionary Maundy Thursday gospel continues with John’s account of Jesus’s last supper with his disciples. But, of course, a lot more happens after that last supper. Jesus heads to the Garden of Gethsemane for some one-on-one conversation with his father, while the disciples tag along. He wants to be alone and asks them to stay and wait for him as he walks on a bit further. Jesus’s distress and agony as well as his fear of what is to come are palpable and are understandably the focus of most discussions of this part of the Holy Week drama.

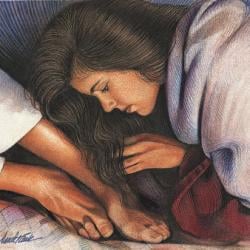

A less discussed, but equally important, detail is that the disciples fall asleep. They literally cannot keep their eyes open. On three different occasions, Jesus returns to them and finds them catching some Zs. Over more than three decades of teaching, many of my students have shown a remarkable ability to fall asleep at the most inopportune times—it’s a common human tendency. The disciples have just had dinner, it’s getting late, they have nothing to do while Jesus is off praying; no wonder they doze off.

A less discussed, but equally important, detail is that the disciples fall asleep. They literally cannot keep their eyes open. On three different occasions, Jesus returns to them and finds them catching some Zs. Over more than three decades of teaching, many of my students have shown a remarkable ability to fall asleep at the most inopportune times—it’s a common human tendency. The disciples have just had dinner, it’s getting late, they have nothing to do while Jesus is off praying; no wonder they doze off.

The gospel accounts are very “high church” sounding, but Jesus is clearly annoyed when he finds them asleep.

DUDES! Really?? I’m over here literally sweating drops of blood, I’ve never been so scared and afraid, and you’re ASLEEP?? Wake the hell up! Can’t you at least do that much?

I’m sure their collective reaction was something like anyone caught sleeping at the time when they should be awake and alert would have been. “Whaa? Oh! I’m not sleeping, I’m just resting my eyes! Sorry, man! James! Andrew! I can’t believe you guys fell asleep! It won’t happen again, bro!” But it does—three times.

On the few occasions I have heard this situation discussed, the focus is always on the disciples, so human, so weak, or so disinterested that they fall asleep at the switch. I’m more interested in Jesus’s reaction. He hasn’t asked the disciples to do anything for him; he doesn’t even want them close by. So why is he so upset to find them sleeping? What’s the difference between doing nothing and being asleep? In one of his letters to Eberhard Bethge from Tegel prison, Dietrich Bonhoeffer uses this little scene to illustrate a profound insight.

Jesus asked in Gethsemane, “Could you not watch with me one hour?” That is a reversal of what the religious person expects from God. We are summoned to share in God’s sufferings at the hands of a godless world.

We expect God to do stuff, to solve problems, to kick butt and take names, but this God is not any of that. The only way this God can be in the world is to experience everything it has to offer, to suffer the worst it can do. The least that the disciples can do is be there, to pay attention, to be in solidarity with this man whom they love, whom they have followed, and whom they absolutely do not understand. Jesus feels alone and abandoned by everyone and everything; finding the disciples asleep simply confirms that what he is feeling is the truth.

What would it mean to watch and not fall asleep, to share in God’s sufferings? Where exactly is God suffering in our world? Everywhere that a human being has a need of any sort, God is in the middle of it. There is so much suffering that it can be overwhelming. No one of us, not even any one group of us, no matter how well-meaning, can make a significant dent. But Jesus isn’t asking the disciples to do anything other than to be aware, to be attentive, and not to tune out. If the answer to “what can I do to help?” is “nothing,” at least the question was asked. Asking someone to bear the weight of the world alone is asking a lot—even of God.

For reflection: Simone Weil writes that “[t]he extreme greatness of Christianity lies in the fact that it does not seek a supernatural remedy for suffering but a supernatural use for it.” Consider her insight in light of the events of Holy Week.