At the beginning of the first seminar in my “Faith and Doubt” colloquium, I asked the fifteen students seated around the table why, when they had more than thirty colloquia to choose from, they had registered for this particular colloquium that meets at 8:30 in the morning twice per week for two hours per session. Their answers were both illuminating and encouraging.

My personal favorite came from a student who explained that he signed up for this colloquium because, a week before registration last fall for spring semester classes, he attended a philosophy club meeting where he heard me give a brief presentation on Simone Weil. The theme of the meeting was “Women in Philosophy”; I was one of three colleagues who presented on a female philosopher who has been important to them over the years. My student said that he was taken my passion in talking about Weil, remembering particularly my noting that my wife calls Simone my “mistress” because of how much time I have spent with her over the last thirty years. “I have to take a class with this guy,” my student thought. Music to my ears.

In the early years of this blog I wrote a post describing my first encounter with Simone Weil—I’m happy to repeat it here.

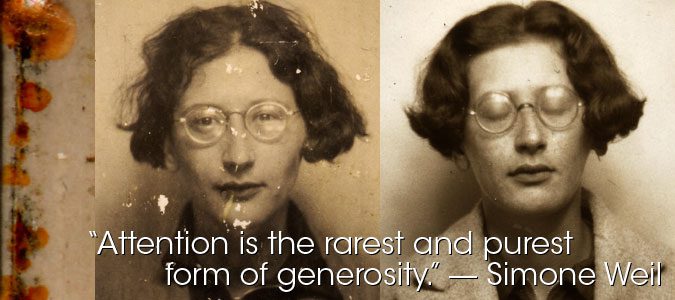

My mistress is not beautiful; she’s not even pretty. She dresses with no regard for what she looks like, usually wearing baggy pants and sweatshirt combinations, together with an ankle length trenchcoat-style garment and a ratty beret to complete the ensemble when she goes out. She chops at her curly hair with a pair of scissors when it gets longer than collar length. She’s nearsighted and wears ugly tortoise-shell glasses. I once saw a picture of her taken when she was twelve years old—the beautiful, innocent, angelic girl with a swan-like neck in the picture bears little resemblance to the adult woman . I’ve sometimes wondered what the hell happened. My mistress hardly ever smiles, has no sense of humor, is intense beyond belief, is incapable of small talk, eats almost nothing, chain smokes like a chimney, and definitely does not suffer fools gladly. Half the time I don’t even like her very much. And yet she has changed my life.

. I’ve sometimes wondered what the hell happened. My mistress hardly ever smiles, has no sense of humor, is intense beyond belief, is incapable of small talk, eats almost nothing, chain smokes like a chimney, and definitely does not suffer fools gladly. Half the time I don’t even like her very much. And yet she has changed my life.

I met Simone during Lent in 1993, at an Episcopal silent men’s retreat of all places. I walked into the large gathering room where a dozen or so silent men were sitting around; she was in the corner, staring in my direction with an intensity that burned a hole through me. She was obviously waiting to be picked up, so I picked her up. I’m not in the habit of picking up strange women on a moment’s notice, but I didn’t seem to have a choice in the matter. I took her with me to a comfortable couch in the corner of the room filled with silent men and we began to talk. Five or six hours later, we were still talking. I took her back to my room with me and we talked through the night; we pretty much talked all the way through the three-day retreat, I guess. I don’t remember much of anything else about it.

I introduced myself to Simone by describing my life as a teacher of philosophy. I was teaching at a small private college which focused on business and engineering. The only reason they needed a philosopher was to teach business ethics, so that’s what I was doing, even though my area of specialization was Early Modern philosophy and my dissertation had been on Descartes. The place paid so poorly that I was teaching four sections of business ethics per semester, three in the day and one in the evening, plus one other course just to make ends meet. I was only in my second year of teaching after getting my PhD, and was not at all convinced (1) that I was a very good teacher or (2) that my students were learning anything. I sure as hell was hoping I hadn’t made a mistake getting into this profession—the lives of my wife and young sons had been disrupted thoroughly in order to make it happen.

Simone told me that she also had taught for a few years here and there. Then she said the most remarkable thing, that she believed the primary importance of school studies begins with “the realization that prayer consists of attention” and that this capacity of attention must be developed “with a view to the love of God.” School studies are crucially important, not because of the content taught, but because “the development of the faculty of attention forms the real object and almost the sole interest of studies.” Only attentive people can love God, and school studies, properly approached, help to develop attentive people.

I thought this to be irrelevant to my frustration with business ethics or insecurities about being a mediocre teacher. I was just about ready to return Simone to where I picked her up from, but then she said something else very interesting.

Contrary to the usual belief, [will power] has practically no place in study. The intelligence can only be led by desire. For there to be desire, there must be pleasure and joy in the work. The intelligence only grows and bears fruit in joy. The joy of learning is as indispensable in study as breathing is in running. Where it is lacking there are no real students, but only poor caricatures of apprentices who, at the end of their apprenticeship, will not even have a trade.

This cut directly across all of my surface level concerns to the heart of the matter. Why did I want to teach philosophy, in many people’s estimation the quintessentially useless field of study? Why did I want to teach at all? Simone had expressed what I had lacked the words for—in my (at that time) thirty-seven years, what brought me the greatest joy, the most intense exhilaration, was the life of learning. Early in my life I had been infected by the love of books and of ideas; when it turned out, after many by-paths, that I was going to spend my life in school, I was not surprised.

I think I had known this was where I belonged from the first day I walked into Miss Bailey’s first grade classroom. And all I wanted to do was pass this infection on to others. All I wanted to do was to help others find the joy in learning that had sustained me through times in my life when there seemed to be nothing else worthwhile except a book. If I was going to be good teacher, that’s what had to be at the heart of it. Simone had given me the words to express what I’d intuited all along, that for me, teaching was a vocation, a sacrament, a holy thing.

She ended that part of our conversation by saying that in her opinion “Academic work is one of those fields containing a pearl so precious that it is worth while to sell all our possessions, keeping nothing for ourselves, in order to be able to acquire it.” I said “I think I love you—want to go home with me?” When I returned home after the retreat, I sat on the kitchen counter while my wife Jeanne was doing kitchen things and tried to introduce Simone to her. I don’t think I made much sense, but Jeanne recognized the energy exuding from my inner glow as something unusual, so she didn’t mind that I’d brought a strange woman home with me. As a matter of fact, it was Jeanne who, a few years later, started calling Simone my mistress because of how much time the two of us spent together.

Simone has changed how I think about myself, about my relationships, about the world around me, and ultimately about what transcends me. She frequently comes with me to class. A few years ago, I received a card at the office from a young woman who had graduated as a philosophy major the previous spring. She was a spectacular student and an even more spectacular human being, one of those wonderful gifts that occasionally drop into a teacher’s life. The card was a thank you card, uncomfortably over the top as the young woman thanked me for a number of things that she probably should have been thanking others or herself for. At the end of the card, she wrote “And above all, Dr. Morgan, thank you for introducing me to Simone.”