Several years ago, just in time for the Christmas holiday season, a new book by Sarah Palin was published. Entitled Good Tidings and Great Joy, with the subtitle A Happy Holiday IS a Merry Christmas, the book was promoted, among other things, as “a fun, festive, thought-provoking book, which will encourage all to see what is possible when we unite in defense of our faith and ignore the politically correct Scrooges who would rather take Christ out of Christmas.” Every fall in recent years various conservative voices have called for like-minded persons to “take Christmas back” from various elements and constituencies seeking to secularize and remove Christ from it.

This strikes me as a relatively recent phenomenon. My upbringing was as conservative Protestant Christian as it comes, yet my family had no problem mixing the baby Jesus in a manger with other not-so-Jesus-like features of the holidays, such as the year I got both a BB gun and a G.I. Joe doll (but don’t call it a doll) under the tree. The violent presents must not have had much of an effect. I do not own a gun nor have I shot one in at least thirty years. I’m glad the Christmas police never came to my house—we would have been in trouble.

But that’s nothing compared to the trouble we would have been in had the Easter police ever showed up at the wrong time. Easter is a confusing holiday for a kid, much more confusing than Christmas. Christmas is dependable—it comes on the same day in December every year. But Easter is confusedly flexible—it can show up on any given Sunday between the middle of March and late April.

I learned as an adult that there is actually a method to when Easter occurs. Easter falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon occurring either on or after the vernal (spring) equinox. Although this formula sounds very new-agey and smacks of Druids and such, it apparently was established at the Council of Nicea in 325. No telling what a bunch of theologians and bishops will do with too much time on their hands. All I knew as a kid was that Easter didn’t seem to know when to show up, except that it was always on a Sunday—with either snow banks or flowers outside, depending on the year.

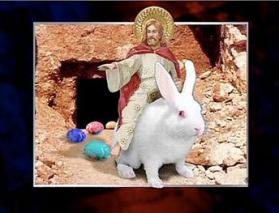

I also knew what Easter was supposed to be about. Jesus was dead and now he isn’t any more. But my real interest was in various not-so-Jesus-like accoutrements that went with Easter—bunnies, Easter baskets, chocolate eggs (crème-filled or hollow) and, my ultimate obsession and downfall, jelly beans. My mother, very much like a Cadbury egg, was solid (or at least Swedish and stoic) on the outside and soft on the inside. She talked a good game about Easter being about Jesus and not about bunnies, eggs, and candy—but my brother and I knew that every Easter morning before we headed off to church would be an early spring version of Christmas morning.

Each of us would find an Easter basket filled with our favorite sweets, as well as a toy or two. Mine was usually a small stuffed animal, facilitating my inexplicable, very strong, and long-lasting stuffed animal obsession. One Easter, my mother said that in addition to the Easter basket, she had hidden two solid chocolate rabbits, one for each of us, somewhere in the house—it was up to each of us to find ours.

My brother found his within five minutes or so slid out of sight but within reach behind the piano. But I could not find mine. I’m usually pretty good at this—Jeanne will attest that I am almost always the “finder of lost or misplaced things” in our house. But I could not find my freaking chocolate rabbit. It came time to head off for church and my mother would have caved and revealed where she had hidden it, except that—typically—she could not remember. I knew better than to suggest that I stay home and find my chocolate rabbit while the rest of the family went to church, but I was not thinking “He is Risen!” thoughts while at the service. I was wondering “where the fuck is my chocolate bunny??” (or something like that—the “f” word had not made it into even my inner—let alone outer—vocabulary yet).

The chocolate rabbit was never found. To his great consternation, my mother made my brother share his rabbit with me. Several weeks later, though, we found out what had happened to my bunny. As I helped my mother move the massive console record player in the corner of the living room so she could clean underneath, we discovered the box that had contained my chocolate rabbit, empty with a large hole chewed in the bottom left corner. My bunny had been confiscated and eaten by one of the several mice who lived in our old barn of a house. We could hear them running behind the walls on occasion. My father set mousetraps in various closets and the furnace room on a regular basis; one of my older brother’s jobs was to check the traps occasionally and discard any unlucky mouse with a broken back that he discovered.

I hoped at the time that the freaking mouse who stole my bunny was one of the ones caught by a trap, or at least that the mouse died of a sugar and chocolate overdose.  But the Easter Mouse has become iconic in my personal mythology over the years, representing the continuing pull of sacred and secular that has evolved from a confusing tension as a child into an endless source of fascination, ideas, and challenges for growth (as well as blog posts!) as an adult. Santa Claus or the baby Jesus? Santa’s elves or the angel Gabriel? Rabbits or an empty tomb? Jelly beans or unleavened bread?

But the Easter Mouse has become iconic in my personal mythology over the years, representing the continuing pull of sacred and secular that has evolved from a confusing tension as a child into an endless source of fascination, ideas, and challenges for growth (as well as blog posts!) as an adult. Santa Claus or the baby Jesus? Santa’s elves or the angel Gabriel? Rabbits or an empty tomb? Jelly beans or unleavened bread?

As I sat toward the back of a full Trinity Episcopal Church for Easter Sunday service a few years ago—something no one will be doing today, unfortunately—I was reminded of something provocative that a good friend of mine once said: “The heart of Christianity is what you believe about the stories. Do you believe the stories are true or don’t you? Yes or No?” In a slightly more formal way, New Testament scholar N. T. Wright has the following to say about the stories:

The practical, theological, spiritual, ethical, pastoral, political, missionary, and hermeneutical implications of the mission and message of Jesus differ radically depending upon what one believes happened at Easter.

Indeed they do—but beyond confirming that I believe the Easter story is true in the sense that “these stories are true—and some of them actually happened,” I not very interested in debates concerning the historical veracity of the foundational stories of Christianity. Personally, I’ll take the Incarnation over the Resurrection as the seminal truth of my Christian faith. But here’s what I do know to be true about Easter:

- I know that resurrection is real because I have experienced it.

- Easter is a reminder that death does not have the last word, that life always springs from what has been left for dead.

- New life is often unexpected, inexplicable and unpredictable. I don’t know what the dozens of little green things that have sprouted up throughout my back yard and flower beds are (I’ve never seen them in previous springs), but they are alive. I don’t know what the little downy woodpecker hammering away on the vinyl siding of our neighbor’s house this morning was thinking, but it was life in action.

As the newly sighted man said when interrogated about the person who healed his blindness, “I don’t know about Jesus but one thing I do know—I was blind and now I see.” My life narrative will always include the language of incarnation and resurrection—that’s my story and I’m sticking to it. This I know for certain: New life is for real.