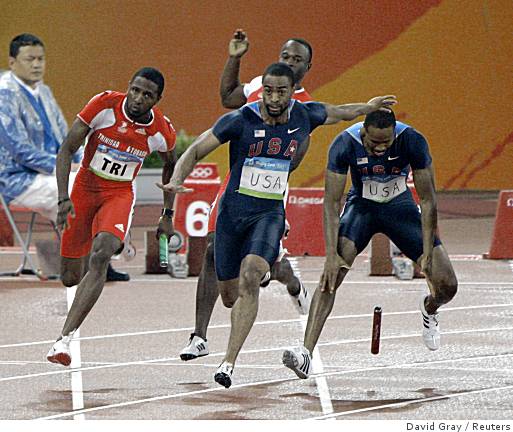

A disturbingly common mishap in recent Summer Olympic games has been the failure of U.S. track and field relay teams. Individually, these teams almost always are made up of the best runners, top to bottom, of any nation’s relay contingent. Best times, best individual win-loss records. But great individuals do not a successful relay team make. In a relay race, each runner is required not only to run her or his lap as swiftly as possible, but also to hand the baton to the next runner smoothly and securely within a specified number of meters. As the baton falls to the track during these attempted transfers, time after time, the truth becomes crystal clear.

In the quintessential American spirit, the members of the U.S. relay teams have spent far too much time honing their individual running skills, and far too little time practicing how to be a team (if they’ve practiced at all). Passing a baton while both the passer and passee are running, one decelerating and one accelerating, within a limited amount of space takes practice, practice that is not nearly as sexy or stimulating as running as fast as one can by oneself.

Baton-passing serves as an interesting analogy for many human situations, particularly generational ones that involve passing a virtual baton from the geezers to the young punks. A successful transfer requires the ability and desire to receive and run on the younger generation’s part and a willingness to let go and slow down from the older veterans. Debate about curriculum reform swirled around my campus for close to a decade before a new core curriculum was established several years ago. The conversations centered on a large, four semester course, described as the “core of the core” at my college, that is required of all freshmen and sophomores. This course was created, and then established as the heart of the college’s core curriculum in the early 1970s, a course that was groundbreaking and audacious in its day.

Many of the faculty who were the “young Turks” of that time, the movers and shakers who invented this course and shepherded it through the faculty senate and administration against all odds, were senior faculty on the verge of retirement during the reform debate. Others have already retired, some have died. And the course they created, which defined many of their academic careers both in the classroom and out, became stale and badly in need of fresh vision and creative reconstruction. Despite the good will of many of the next generation of faculty, highly qualified and motivated women and men who willingly seek to carry a revitalized course forward for the next few decades, the reform debate was frequently poisoned by the resistance to any meaningful change by the older generation. It has been sad to observe.

By accident of age and time served at the college I was positioned, as both one of the youngest of the older generation and one of the most experienced of the new generation, at the very point where the baton transfer should occur. As a veteran of teaching in this program and a long-standing advocate for needed change, I was eventually asked to direct the new version of this program that emerged from curriculum reform as it transitioned from the past into the future. My years as director were largely successful, in spite of some continuing resistance. As I’ve told several of my senior colleagues over the past few years, “it’s impossible to run a relay race if you won’t let go of the baton.”

Tomorrow is Ascension Sunday. Thirteen years ago, Ascension Sunday happened to be the seventeenth and last Sunday that I would be worshiping at St. Johns Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota on sabbatical. As I sat in my choir stall seat during seven-o’clock morning prayer, then in the sanctuary later in the morning during mass, there was a certain wistfulness and a bit of emotion, but not as much as I expected. For this Ascension Sunday was an appropriate milestone in my spiritual growth, a marker of the point at which I would tentatively and with fear and trembling take what I had learned and experienced over the previous four months “into all the world.”

I was never taught to pay attention to Ascension Sunday in my religious tradition. But even after I was introduced to the liturgical calendar for the first time in my middle twenties, Ascension Sunday was simply the Sunday before Pentecost, after which we would slog through week after week of Ordinary Time boredom in green through the summer and fall until we were rescued by Advent purple right after Thanksgiving. But as I inhabited for the first time the psalms and New Testament texts on that Ascension Sunday, I thought “Wow. Jesus was the ultimately prepared and successful baton passer.”

In one way, Ascension Sunday completes the story of the Incarnation that began with Jesus’ birth. Jesus doesn’t ascend out of his human body to heaven—he takes it with him, because the next lap of this story, the “Christ in us” lap, is just about ready to explode. Jesus showed extraordinary patience with his all-too-human followers during his short stay on earth, teaching them basic truths through stories and actions, all preparation for when it would be up to them to receive the baton and run their own incarnational race. The forty days after the Resurrection were all practice for a smooth passing of the baton.

Jesus kept telling them “It’s all right. I’m not leaving you alone. It’s better for you that I am leaving, because I’ll be sending you the greatest teammate ever. You can do this, because I’ll still be with you. When I leave, don’t go crazy and start running in every direction out of fear or impatience. Wait. Pray. You’ll know when it’s time to run. And when you do, you’ll turn the world upside down.” And when the clouds closed on Jesus’ heels as he ascended into heaven, for once the men and women who had loved and followed him did what they were told. They went into an upper room in Jerusalem and waited.

I’m told that the receiver of the baton in a relay race should not seek to accelerate until she or he feels the slap of the baton in the palm of the receiving hand they have extended backwards as they begin to run. The receiver never sees the runner coming up behind, but there’s no mistaking the transfer from the unseen runner when it happens. And in the upper room ten days after Jesus left, there was no mistaking that the baton had been successfully transferred.

The Incarnation goes on, and we recipients of the Holy Spirit carry it “to the ends of the earth.” In his homily on that Ascension Sunday, the Abbott observed that with Ascension Day, the Easter message of “Glory, Glory, Glory” that has been front and center since Easter changes to “Go!” The word to me that day and ever since was “Take what you’ve been given, what you’ve found, and go.” As my favorite Psalm says,

Day unto day takes up the story

And night unto night makes known the message.

We are carrying the baton, and are to run as if our lives depended on it. Because they do.