As predictable as the change of seasons is the point in any given semester when students will approach me for the first time and ask for out of class help. ![images[11]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/10/images11.jpg?w=150) Usually it’s after the first exam or paper has been returned. Students with dreams of an “A” dancing in their heads tend to make an appointment when their first major piece of graded work has a “C” or “D” on the top of it. I’m a user-friendly professor and am more than happy to meet with any student; when first approached, I usually raise the student’s eyebrows when I direct the student to be sure and bring the appropriate texts along for the appointment.

Usually it’s after the first exam or paper has been returned. Students with dreams of an “A” dancing in their heads tend to make an appointment when their first major piece of graded work has a “C” or “D” on the top of it. I’m a user-friendly professor and am more than happy to meet with any student; when first approached, I usually raise the student’s eyebrows when I direct the student to be sure and bring the appropriate texts along for the appointment.

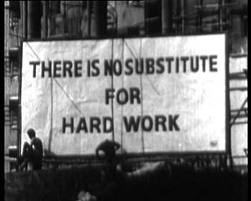

When Jane comes to my office, conversation begins with her saying something along the lines of “I don’t understand why I did so poorly—I’ve done all of the readings and haven’t missed any classes.” I know whether the latter claim is true already, and will be checking on the first claim shortly. First, however, I tell Jane that “whatever I suggest in terms of strategies or help is going to require more time and more work from you. If you’re looking for a way to do better in the class without working harder than you have been already, there is no such way.” This is undoubtedly a disappointment, since the reason Jane made the appointment was to get the “magic bullet” that will slay the dreaded “C” or “D” and make room for the “A” to which she believes she is entitled. Learning that there is no such magic bullet is never good news.

First, however, I tell Jane that “whatever I suggest in terms of strategies or help is going to require more time and more work from you. If you’re looking for a way to do better in the class without working harder than you have been already, there is no such way.” This is undoubtedly a disappointment, since the reason Jane made the appointment was to get the “magic bullet” that will slay the dreaded “C” or “D” and make room for the “A” to which she believes she is entitled. Learning that there is no such magic bullet is never good news.

And it gets worse, as I next ask to see her texts. They look as if they had just been taken off the bookstore shelf—no dog-eared pages, no scribbled notes in the margin, no underlined passages, no highlighted texts—and Jane’s name isn’t even in it. Handing my heavily underlined, highlighted and annotated copy of the same text to Jane, I remark that “here’s problem number one. Your text should look like this. ” I even go so far as to provide her with the key to my quirky markings, according to which I highlight in yellow the first time through, focusing the second time through primarily on the highlighted areas and underlining with a black pen those part that appear most crucial. Then after class I return a third time to write notes and comments from class discussion in the margins. Not only will following something like this procedure lock the material into the student’s memory by requiring something more than simply looking at words, but it will also condense the material for reviewing purposes when exam time comes.

” I even go so far as to provide her with the key to my quirky markings, according to which I highlight in yellow the first time through, focusing the second time through primarily on the highlighted areas and underlining with a black pen those part that appear most crucial. Then after class I return a third time to write notes and comments from class discussion in the margins. Not only will following something like this procedure lock the material into the student’s memory by requiring something more than simply looking at words, but it will also condense the material for reviewing purposes when exam time comes.

I lost Jane’s attention as soon as she saw my copy of the text. Even though Jane doesn’t know what the colors and markings mean, she at least knows that they mean a lot of work. You mean I have to read more than once? That I have to read and think critically? That I have to read it again after class? You’ve got to be kidding! That’s going to take a lot of time and effort! And indeed it will. Jane has been introduced for the first time to the fine print in the life of learning—it’s hard. It requires building good reading and study habits. True education isn’t for lazy people and it isn’t for sissies. And it certainly isn’t for anyone who wants to cut corners, to get to a desired outcome without taking all of the necessary steps in between. Every one of them.

That’s going to take a lot of time and effort! And indeed it will. Jane has been introduced for the first time to the fine print in the life of learning—it’s hard. It requires building good reading and study habits. True education isn’t for lazy people and it isn’t for sissies. And it certainly isn’t for anyone who wants to cut corners, to get to a desired outcome without taking all of the necessary steps in between. Every one of them.

Mark’s gospel from last Sunday includes a classic “fine print” experience. A young man (called a “certain ruler” in the Luke version of the story) approaches Jesus and asks “What shall I do that I may inherit eternal life?” Jesus answers that the young man knows very well what to do—he should keep the commandments. Jesus lists a few for the guy, just in case he had forgotten them. But the young man replies “Teacher, all these I have done from my youth.” He’s not looking for a “good boy” pat on the head from Jesus; he’s already past the point of thinking that simply following the rules is good enough, or he wouldn’t have asked in the first place. The young man is looking for more. He’s thinks that he’s ready for the fine print.

Mark’s gospel from last Sunday includes a classic “fine print” experience. A young man (called a “certain ruler” in the Luke version of the story) approaches Jesus and asks “What shall I do that I may inherit eternal life?” Jesus answers that the young man knows very well what to do—he should keep the commandments. Jesus lists a few for the guy, just in case he had forgotten them. But the young man replies “Teacher, all these I have done from my youth.” He’s not looking for a “good boy” pat on the head from Jesus; he’s already past the point of thinking that simply following the rules is good enough, or he wouldn’t have asked in the first place. The young man is looking for more. He’s thinks that he’s ready for the fine print.

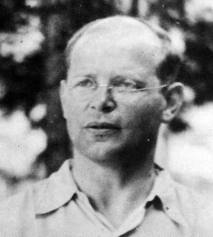

We all know Jesus’ response—he reads him the fine print. “Go your way, sell whatever you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, take up the cross, and follow me.”![59921[1]](http://wp.production.patheos.com/blogs/freelancechristianity/files/2012/10/599211.jpg?w=150) We also know the end of the story—“He was sad at this word, and went away grieved, for he had great possessions.” The fine print demanded the one thing the young man could not do. But what precedes Jesus’ reading of the fine print is even more interesting. Mark says that “Jesus, looking at him, loved him.” This is a man who wants more, Jesus knows it, and Jesus loves him for it. But that damned fine print—the thing that you cannot do, that’s the thing that is required. And it will be something different for each of us. This story isn’t about the incompatibility of wealth and following Jesus at all. It’s about the fact that, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer

We also know the end of the story—“He was sad at this word, and went away grieved, for he had great possessions.” The fine print demanded the one thing the young man could not do. But what precedes Jesus’ reading of the fine print is even more interesting. Mark says that “Jesus, looking at him, loved him.” This is a man who wants more, Jesus knows it, and Jesus loves him for it. But that damned fine print—the thing that you cannot do, that’s the thing that is required. And it will be something different for each of us. This story isn’t about the incompatibility of wealth and following Jesus at all. It’s about the fact that, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer  wrote, “ when Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” The God of love is not a cure for anything. The God of love is the greatest of all disturbers of the peace. “I did not come to bring peace but a sword,” and this is a sword that cuts deepest in those who are the most obsessed with knowing God.

wrote, “ when Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” The God of love is not a cure for anything. The God of love is the greatest of all disturbers of the peace. “I did not come to bring peace but a sword,” and this is a sword that cuts deepest in those who are the most obsessed with knowing God.

This is a disturbing story because it absolutely runs roughshod over our idea that human dealings with God are transactional. “What do I need to do in order for X to happen, in order for Y not to happen, in order for Z not to die?” is the question we so often want answered, and this sort of question is always wrong when directed toward the transcendent. While on sabbatical I heard the poet Michael Dennis Browne![MDB%204%20web[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/10/mdb20420web1.jpg?w=150) speak of an insight that unexpectedly came to him as he mourned the tragic death of his younger sister, a woman for whom family and friends had gone hoarse with their prayers and petitions for healing. And she died anyways. What the hell is going on? Browne said “It came to me that this is not a God who intervenes, but one who indwells.” That changes everything, in ways I’m not sure I’m fully ready to think about yet. But the following from Rainer Maria Rilke gives me hope:

speak of an insight that unexpectedly came to him as he mourned the tragic death of his younger sister, a woman for whom family and friends had gone hoarse with their prayers and petitions for healing. And she died anyways. What the hell is going on? Browne said “It came to me that this is not a God who intervenes, but one who indwells.” That changes everything, in ways I’m not sure I’m fully ready to think about yet. But the following from Rainer Maria Rilke gives me hope:

![images[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/10/images1.jpg?w=130) So many are alive who don’t seem to care.

So many are alive who don’t seem to care.

Casual, easy, they move in the world

As though untouched.

But you take pleasure in the faces

Of those who know they thirst.

You cherish those

Who grip you for survival.

You are not dead yet, it’s not too late

To open your depths by plunging into them

And drink in the life

That reveals itself quietly there.