One of the many things I enjoy about the teaching profession is creating new courses. A friend and colleague from the political science department (who is also a Dominican priest) and I are in the early stages of planning a new, team-taught course called “Faith and Doubt” that we plan to teach in the Spring 2022 semester. As anyone who reads this blog occasionally knows, the importance of doubt to a vibrant and living faith is one of my favorite topics to write about. This is going to be fun.

I’m a great lover of mysteries; this summer, my newest find is Elly Griffiths’ Ruth Galloway mystery series. Set in the Norfolk area of England, the series focuses on Ruth Galloway, a forensic archaeologist who lectures at the local university, and Harry Nelson, a DCI in the local police force. Griffiths is a fine writer, high on atmosphere and character development, relatively restrained when it comes to violence and sex—a little bit like my favorite mystery writer, Louise Penny. In keeping with my binge-reading tendencies, I binge read all twelve of the books in the series and am impatiently waiting for number thirteen.

Ruth Galloway is one of the most interesting fictional characters I’ve encountered in a long time. Her parents became evangelical Christians when she was ten years old, disrupting and changing her life in ways that I—raised in evangelical Christianity—resonate with completely. Her adult way of dealing with her religious childhood is to be highly skeptical of religion in general and of all faith claims. Her skepticism is frequently challenged, since the dozen or so repeating characters swirling around Ruth include lapsed Catholics, faithful Catholics, nominal Anglicans, people who have visions of and communicate with dead saints, fellow survivors of evangelical Protestantism, atheists, agnostics, and a druid.

In one of the later volumes in the series, Ruth reconnects with Hilary, a friend from graduate school whom she has not seen for twenty years. When they meet up at a local café, Ruth is shocked to see that Hilary is wearing a “dog collar.” She’s an Anglican priest. After a few minutes, Hilary gives the condensed version of what caused her to transition from newly minted professional archaeologist to seminary and the priesthood.

I worked as an archaeologist for a while, did some fantastic digs . . . But then . . . I found God.

Given her history, Ruth finds this story frustrating and perplexing.

Why do people keep doing that? Ruth’s parents discovered God when she was ten, and her life was never the same again. Why couldn’t He just stay hidden?

It’s a great question. And how one answers the question reveals a lot about how one imagines the relationship between human beings and this elusive something we call “God.”

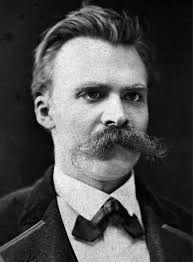

Ruth’s annoyed question reminds me of an infamous/famous passage from one of the most infamous/famous philosophers in the Western tradition. In The Joyful Wisdom, Friedrich Nietzsche tells the story of “the Madman.”

Have you not heard of that madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning hours, ran to the market place, and cried incessantly, “I seek God! I seek God!” He provoked much laughter. Why did he get lost? said one. Did he lose his way like a child? said another. Or is he hiding? Is he afraid of us? Has he gone on a voyage? Or emigrated? Thus they yelled and laughed.

It is indeed a humorous idea, that God is hiding, as well as the notion that one might find God if one looks in the right place and for a long enough time. But the prophet Isaiah writes “Indeed you are a hidden God,” while the book of Proverbs tells us that “It is the glory of God to conceal a thing, and the glory of kings to search it out.” Apparently, God likes to hide and conceal, so much so that those who claim to be in possession of the divine and all of its characteristics, personality traits, likes and dislikes, as well as possessing tools appropriate for distinguishing who is godly and who is not, are probably in possession of something other than God. Most likely a projection of themselves.

It is indeed a humorous idea, that God is hiding, as well as the notion that one might find God if one looks in the right place and for a long enough time. But the prophet Isaiah writes “Indeed you are a hidden God,” while the book of Proverbs tells us that “It is the glory of God to conceal a thing, and the glory of kings to search it out.” Apparently, God likes to hide and conceal, so much so that those who claim to be in possession of the divine and all of its characteristics, personality traits, likes and dislikes, as well as possessing tools appropriate for distinguishing who is godly and who is not, are probably in possession of something other than God. Most likely a projection of themselves.

Why is God hiding? Why is God so often silent? Returning to Nietzsche’s story of the Madman, we are confronted with a shocking possibility.

The madman jumped into their midst and pierced them with his glances. “Where is God?” he cried. “I shall tell you. We have killed him—you and I . . . God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we, the murderers of all murderers, comfort ourselves? . . . What are these churches now if they are not the tombs and sepulchers of God?”

Few claims as controversial as “God is dead” have ever been made. Unfortunately, it’s usually a conversation stopper rather than the conversation starter that Nietzsche undoubtedly intended. Far from claiming that there once was an old guy with white hair and a beard in heaven who was infected with Covid-19 or some other disease and died, Nietzsche’s shocking statement challenges us to investigate what we even mean when we say the word “God.”

It’s such a simple word, a noun that plays the role of “person, place, or thing” in sentences perfectly well. If God is an object, that is. Objects can be hidden and found, misplaced and discovered, contained, used, weaponized, preserved, worshipped and revered, or discarded and forgotten. God has been used in all of those ways, and many more. Although it is clear from Nietzsche’s body of work that he was a dedicated atheist, he was also fascinated by and obsessed with religion, claims to faith, and how belief in God can shape one’s attitudes, morals, and experiences.

When the Madman proclaims the death of God, he is levelling a devastating indictment against those who “believe that God exists,” but do not believe in God. If one believes that God “exists,” one is placing God in the category of “stuff that exist” like chairs, computers, cats, pens . . . “person, places, and things,” in other words. Belief in God leads to a life changed because of a dedication and commitment to an elusive something that can be sought, grappled with, loved, hated, and embraced—but never “found” in the sense of contained, owned, or controlled.

When Nietzsche says that “God is dead,” he is asking those who claim to be followers of the divine whether what they claim to believe truly makes a difference in how they live their daily lives, or whether they are simply saying fancy words that sound appropriate, but that refer to something that looks for all the world like a corpse, for all the difference it makes in their lives.

This is why Blaise Pascal, one of the greatest apologists for the Christian faith who ever lived, wrote that “every religion that does not confirm that God is hidden is not true.” This is why Jesus talked about the Kingdom of Heaven in parables and similes rather than making direct claims and comparisons. What if God does not want to be “found”? What if God is not an object, or even a noun? God is a way of life, a commitment, that will be as individual and unique as those who live out those commitments are.

There are many churches and religions that are undoubtedly, as Nietzsche so memorably described them, “tombs and sepulchers of God.” What they claim to revere, worship, and care about has been dead for a long time—and it shows. God is not something to be found. God is to be lived.