Every fall I get to spend several weeks with a bunch of freshmen in the wonderful world of ancient Greek literature and philosophy; two weeks ago it was Herodotus, last week Aeschylus, this week Plato. These guys make you think! Here’s what I was thinking last fall–similar thoughts this year.

Jeanne got on the Amtrak early one Sunday morning not long ago, beginning two weeks of work-related travel. Bummed out, I decided to head south for church an hour and a half early in order to spend that extra time in a nice little coffee shop just down the road from Trinity Episcopal, reading and doing my introverted thing. ![herodotus[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/12/herodotus1.jpg?w=186) My text for the morning was Herodotus’s Histories, the primary text for the coming week’s Development of Western Civilization freshman seminars.

My text for the morning was Herodotus’s Histories, the primary text for the coming week’s Development of Western Civilization freshman seminars.

Herodotus is considered to be the first true historian, but historian or not, he’s a great story-teller. His “history” is often page after page of anecdotal tales about strange and distant lands, often based more on second-hand rumor than direct observation. Consider, for instance, his description of a certain Thracian tribe’s practices at the birth of a baby:

When a baby is born the family sits round and mourns at the thought of the sufferings the infant must endure now that it has entered the world, and goes through the whole catalogue of human sorrows; but when somebody dies, they bury him with merriment and rejoicing, and point out how happy he now is and how many miseries he has at last escaped.

That’s a sixth-century BCE version of “life’s a bitch and then you die,”![lifes-a-bitch[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/12/lifes-a-bitch1.jpg) codified into the very fabric of a culture. The first stop on Jeanne’s two-week travels was to stop in New Jersey briefly to help celebrate the first birthday of her great-niece with her family. Something tells me that Emma’s first birthday was not marked with a recitation of “the whole catalogue of human sorrows.”

codified into the very fabric of a culture. The first stop on Jeanne’s two-week travels was to stop in New Jersey briefly to help celebrate the first birthday of her great-niece with her family. Something tells me that Emma’s first birthday was not marked with a recitation of “the whole catalogue of human sorrows.”

But if brutal honesty were the rule of the day, perhaps her Emma’s first birthday celebration should have been so marked. The ancient Greeks, Herodotus included, understood better than any group of people before and perhaps since the often tragic tension that lies just below the surface of human life. In Aeschylus’s Oresteia![full[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/12/full1.jpg?w=300) , the trilogy of plays that was the previous week’s focus with my DWC freshmen, we encountered the horribly messy history of the house of Atreus, undoubtedly the most dysfunctional and f–ked up family in all of literature. In this midst of this powerful and tragic work, Aeschylus occasionally reminds us that tragedy and pain is not just part of myth and legend—it is an integral part of the human condition. We must, Aeschylus writes, “suffer into truth.”

, the trilogy of plays that was the previous week’s focus with my DWC freshmen, we encountered the horribly messy history of the house of Atreus, undoubtedly the most dysfunctional and f–ked up family in all of literature. In this midst of this powerful and tragic work, Aeschylus occasionally reminds us that tragedy and pain is not just part of myth and legend—it is an integral part of the human condition. We must, Aeschylus writes, “suffer into truth.”

At the risk of “piling on,” here’s one more observation about the darkness that often envelops human existence. In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche tells the ancient tale of King Midas, who spends a great deal of energy and time ![midas_silenus[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/12/midas_silenus1.jpg?w=300) chasing down the satyr Silenus in order to ask him a simple question: “What is the very best and most preferable of all things for man?” Silenus’ response: “Why do you force me to tell you what it is best for you not to hear? The very best of all things is completely beyond your reach: not to have been born, not to be, to be nothing. But the second best thing for you is – to meet an early death.” To which I’m sure Silenus added: “Have a nice day!”

chasing down the satyr Silenus in order to ask him a simple question: “What is the very best and most preferable of all things for man?” Silenus’ response: “Why do you force me to tell you what it is best for you not to hear? The very best of all things is completely beyond your reach: not to have been born, not to be, to be nothing. But the second best thing for you is – to meet an early death.” To which I’m sure Silenus added: “Have a nice day!”

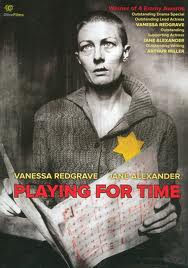

As the main character in the movie “Playing for Time,” played by Vanessa Redgrave, says in the aftermath of the horrors of Auschwitz, “we’ve found something out about ourselves, and it isn’t good news.” The texts and stories mentioned above are pre-Christian—apparently the ancient Greeks did not need a doctrine of original sin to notice that there’s something seriously wrong with human beings. In the words of John Henry Newman, we are afflicted by “some aboriginal calamity.” And we need help, the sort of help that the mere elimination of headline tragedies and sources of suffering would not provide. The human condition is not a generally pleasant state that is inexplicably and unpredictably invaded on occasion by events both tragic and destructive. It’s much worse than that because evil, tragedy and suffering are woven into the very fabric of human nature. Anne Lamott opens her just-released book Help, Thanks, Wow with these lines from Rumi:

As the main character in the movie “Playing for Time,” played by Vanessa Redgrave, says in the aftermath of the horrors of Auschwitz, “we’ve found something out about ourselves, and it isn’t good news.” The texts and stories mentioned above are pre-Christian—apparently the ancient Greeks did not need a doctrine of original sin to notice that there’s something seriously wrong with human beings. In the words of John Henry Newman, we are afflicted by “some aboriginal calamity.” And we need help, the sort of help that the mere elimination of headline tragedies and sources of suffering would not provide. The human condition is not a generally pleasant state that is inexplicably and unpredictably invaded on occasion by events both tragic and destructive. It’s much worse than that because evil, tragedy and suffering are woven into the very fabric of human nature. Anne Lamott opens her just-released book Help, Thanks, Wow with these lines from Rumi:

You’re crying: you say you’ve burned yourself.![rumiport[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/12/rumiport1.jpg?w=108)

But can you think of anyone who’s not

hazy with smoke?

No, I can’t.

So what to do? The upcoming Advent season is the season of expectation and hope, energized by the desire that we can be better, that “life’s a bitch and then you die” need not be the final word concerning the human story. The truth of human suffering, of course, is embedded in the Christian narrative, about which Simone Weil writes that “The genius of Christianity is that it does not provide a supernatural cure for suffering, but provides a supernatural use.” The Incarnation that Advent anticipates is the beginning of this narrative; t![IMG_0091[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/12/img_00911.jpg?w=300) he promise of Advent is that there is a glimmer of light in the distance that is about to dawn—“In the tender compassion of our God, the dawn from on high shall break upon us.” A rumor of legitimate hope is about to literally be fleshed out. As we turn our attention away from our obsession with the human condition toward distant promise, we choose to believe that when the divine takes on our human suffering and pain, we in turn take on divinity itself. The choice to look outward in expectation is within our power, as this text from Baruch describes:

he promise of Advent is that there is a glimmer of light in the distance that is about to dawn—“In the tender compassion of our God, the dawn from on high shall break upon us.” A rumor of legitimate hope is about to literally be fleshed out. As we turn our attention away from our obsession with the human condition toward distant promise, we choose to believe that when the divine takes on our human suffering and pain, we in turn take on divinity itself. The choice to look outward in expectation is within our power, as this text from Baruch describes:

Take off the garment of your sorrow and affliction, and put on forever the beauty of the glory from God.

Help is on the way.