In the aftermath of Easter, Christians often enjoy retelling various stories about Jesus from the New Testament. “But they are just stories,” the skeptics say, no different than the myths and legends of Greek mythology or the tales of King Arthur, similar to the way in which those who wish to dismiss Darwin say that his theory of natural selection is “just a theory.”But sometimes a theory is more than just an educated guess, and sometimes a story is more than an entertaining piece of fiction. This is one of those times.

Judging from the New York Times best seller list, the past ten or fifteen years have been good ones for atheists. Thanks to the “New Atheists,” from Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett to the late Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins, it has never been trendier and more acceptable to critique all manners of religious belief and commitment, placing God in the dustbin of ideas whose time has come and gone. The word seems not to have filtered down to the rank and file in this country—the United States, according to poll after poll, remains extraordinarily religious—but for those “in the know,” certainty about God’s non-existence can be fashioned from any number of educated sources from a multitude of disciplines and interests.

Most “new atheist” tomes define “religious belief” and “God” in extraordinarily narrow and comically uninformed terms. Apparently Sam, Dan, Richard, and Christopher have never met a living, breathing person of faith, a person committed to a framework of belief that evolves, grows, and deepens in the midst of doubt, fear and uncertainty. There is no one definition of God to be proven wrong—I would go so far as to suggest that for many theists, God is more of a verb than a noun, more of an action than an object or item whose existence needs to be verified.

Not long ago, I read the first few pages of Greg Epstein’s Good without God. Epstein is the Humanist chaplain at Harvard University; Jeanne gave me a heads up after she heard him being interviewed on NPR. I appreciated the first few pages of Epstein’s introduction, where he takes the new atheists to task for their failure to take religious belief seriously, but it was Epstein’s definition of God that fully caught my attention.

Humanists believe that God is the most important and influential literary character that human beings have every created.

Really. For a moment I couldn’t decide whether that was highly offensive or something worth taking seriously.

Epstein’s definition brought to mind a passage from Richard Rorty, whose work I like a great deal. Rorty was an atheist, but wrote many fascinating and insightful things about pedagogy, democracy, philosophy, religious belief, and more. About texts that inspire, Rorty wrote that

To have inspirational value, a work must be allowed to recontextualize much of what you previously thought you knew . . . [inspired teaching] is the result of an encounter with an author, character, plot, stanza, line or archaic torso which has made a difference to the [teacher’s] conception of who she is, what she is good for, what she wants to do with herself: an encounter which has rearranged her priorities and purposes.

Recontextualizing much of I previously thought I knew—making a difference to my conception of who I am—an encounter which has rearranged my priorities and purposes—that sounds a lot like God. Not bad for an atheist, Richard. In this light, Epstein’s definition of God is not offensive at all; on the contrary, I love the idea of God as a story, as God as text. Go for it.

Just about every religion imaginable is full of stories, and Christianity is no exception. In the stories of the Old and New Testaments, I dare you to find one important character whose encounter with God did not recontextualize and rearrange (or perhaps disarrange) everything that character thought he or she knew.

From Abraham, Moses, Deborah, David, and Esther to Zechariah, Mary, Mary Magdalene, Peter, Nicodemus and Saul/Paul, the pages of the Bible and the traditions flowing from it are strewn with transformed priorities and redirected purposes. The transformation is not the result of reading a powerful book, no matter how inspired, but encountering a living, dynamic story whose primary divine character explodes expectations and dismantles assumptions at a glance.

Concerning this dynamic, Annie Dillard quotes C. S. Lewis’s remark that “a young atheist cannot be too careful of his reading.” Continuing in her essay “The Book of Luke,” Dillard suggests that the Bible, itself nothing but an outdated tome, again and again opens doors for the unsuspecting that, once open, can never be shut.

This Bible, this ubiquitous black chunk of a best-seller, is a chink—often the only chink—through which winds swirl . . . We crack open its pages at our peril. Many educated, urbane, and flourishing experts in every aspect of business, culture, and science have felt pulled by this anachronistic, semi-barbaric mass of antique laws and fabulous tales from far away; they entered its queer, strait gates and were lost.

Dillard’s parents often sent her to Bible camp in the summer—Annie wants to know “what we they thinking?”

Why did they spread this scandalous document before our eyes? If they had read it, I thought, they would have hid it. They did not recognize the lively danger that we would, through repeated exposure, catch a dose of its virulent opposition to their world.

If you want to have your priorities and purposes rearranged permanently, jump into the middle of this greatest story ever told and start looking for the main character. You will never be the same.

But God as a fictional character? God as a text? Is God just a figment of the ever-creative human imagination? That’s seems a bit “out there” even for a freelance Christian. But maybe not. Consider, for instance, Yann Martel’s Booker Prize winning 2001 novel Life of Pi, made into an Academy Award-winning movie a few years ago.

Pi Patel, the lone survivor of a shipwrecked Japanese freighter, has just been rescued after more than two hundred days in a lifeboat. Representatives of the insurance company arrive in Pi’s hospital room in hopes of finding out why the ship sank. Pi’s story, which forms the heart of the book, is spectacularly entertaining and completely unbelievable. In addition to the human passengers who include Pi’s father, mother and brother, the ship is carrying dozens of caged zoo animals. Pi is the only human survivor of the disaster, and finds himself sharing the lifeboat with an injured zebra, an orangutan, a hyena, and a four hundred fifty pound Bengal tiger named Richard Parker.

Before long the hyena kills the zebra and orangutan, the tiger kills the hyena, and it is just Pi and Richard Parker. For more than seven months they share the boat, working out a tenuous survival relationship and together encountering remarkable adventures including flocks of flying fish, tiger sharks, and a carnivorous island. Upon finally washing ashore in Mexico, Richard Parker walks off into the jungle without so much as a glance back, and Pi is rescued by several conspecifics.

Pi’s story is entertaining, but entirely unacceptable for the insurance claim report.

Pi: What do you want from me?

Insurance guy: A story that won’t make us look like fools. A simpler story for our report. A story the company can understand. A story we can all believe.

Pi: A story without things you’ve never seen before?

Insurance guy: That’s right.

Pi: Without surprises, without animals or islands?

Insurance guy: The truth.

So Pi tells them another story. In this story there are no animals, but Pi is joined on the lifeboat by an injured sailor, the ship’s cook, and Pi’s mother. It is a story of violence, evil, treachery, cannibalism and murder. Eventually Pi is the only human left, and survives alone for several months before bumping into Mexico.

Insurance guy: That’s a terrible story.

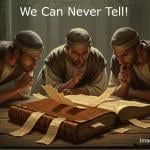

Pi: Neither story explains what happened to the ship, and no one can prove which is true and which is not. So which story do you prefer?

Insurance guy: The one with the tiger. That’s the better story.

Pi: And so it goes with God.

And so it does. We can weave the details of our lives and our reality into a story of “yeastless factuality,” as Pi would describe it, in which we allow no characters or events beyond those that we think we have already figured out.

But the human heart is attuned to a different story, one in which much is uncertain, many things are unknown, a story that we are both characters in and authors of. Holy Week and its aftermath is a story containing at its core this same unpredictable character both human and divine, a character of infinite surprise energizing the story with boundless love and mystery. It’s a much better story. Let’s live it out.