An item popped up on my Facebook news feed not long ago reporting that Harper Lee’s classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird had recently been pulled from a junior-high reading list in a Mississippi school district. Lee’s novel has raised controversy ever since its publication for racist language and dated racial stereotypes, but in this case the explanation for banning the book was straightforward. The school board president reported simply that the book “makes people uncomfortable.”

As a teacher who regularly has to navigate the swamp of “trigger words” in the classroom, I freely admit that “uncomfortable” is one of mine. Every time someone tells me that a book, topic, or conversation makes them “uncomfortable,” I respond that “comfort is vastly overrated.” I thank Vera Brittain for this insight. Many years ago, I read a paragraph in her Testament of Youth that was the single most helpful piece of advice I ever received concerning teaching.

There is still, I think, not enough recognition by teachers of the fact that the desire to think–which is fundamentally a moral problem–must be awakened before learning can occur. Most people wish above all else to be comfortable, and thought is a pre-eminently uncomfortable process.

The idea of thinking and learning as being intimately connected to the desire to think and learn has driven my pedagogy for a long time.

But perhaps even more important is Brittain’s claim that wanting to think and learn is a moral issue. In our contemporary world, learning is often understood in terms of processing information and then applying it, usually with a view to becoming a more and more efficient and productive member of society. But how might the cultivation of thought and learning be transformed if we paid close attention to the moral aspects of these foundational human activities?

Hannah Arendt once said that “every year the world is invaded by millions of tiny barbarians. We call them children.” We all know that part of the process of civilizing these tiny barbarians is equipping them with values and with a moral compass, as well as providing training in how to use these moral tools. If thinking well and being committed to lifetime learning is part of being a moral human being, then muddled and sloppy thinking, as well as the attitude that no additional learning is necessary, are moral failings of the same order as lying, cheating, and stealing.

We live in a world in which we are in danger of—if we have not already arrived at—cognitive immorality. Not because of the immoral contents of our thoughts, but rather because of our collective unwillingness to commit to the hard work of thinking clearly, work that takes the sort of time and commitment that modern human beings are often loathe to engage with.

In a recent interview on Krista Tippett’s On Being, Maria Popova said this:

As a culture, we seem somehow bored with thinking. We want to instantly know. We’ve been infected with this kind of pathological impatience that makes us want to have the knowledge but not do the work of claiming it. The true material of knowledge is meaning. And the meaningful is the opposite of the trivial. And the only thing that we have gleaned by skimming and skipping forward is really trivia. The only way to glean knowledge is contemplation. And the road to that is time. There’s nothing else.

I can think of no better contemporary example of this than our current political cycle. In a perfect world, candidates for office would be held to high standards of thoughtfulness, coherence, and relevance. Rather, there appears to be general agreement with Violet, Dowager Countess of Downton Abbey, who once quipped that “All this thinking is overrated.” As Nicolle Wallace said yesterday in the aftermath of President Trump’s town hall event the evening before, “The country has been deprived of a thinking President.”

But cognitive immorality goes deeper than the Presidency. Our general attitude is that a candidate telling us “I will do this” should be enough—why insist on an explanation or account of how this will be done? Most of us remember being told on a middle or high school mathematics exam to “show your work”—no shortcuts allowed, in other words. How then have we come collectively to a place where we cannot be bothered to “show our work” when it comes to decisions that will affect generations?

During my childhood and adolescent years, I was occasionally told, particularly by family members and people who attended our church, that “you think too much.” A corollary was often that “things really aren’t that complicated.” The truth, of course, is that there are very few times in life where more thought is unnecessary, and things really are that complicated.

There is a strong tendency in human nature to want things simplified; even more, there is a strong desire to move from premise to conclusion without having to do any of the nasty and time-consuming work in between. Part of moral and cognitive maturity is to move forward with intelligence and conviction through a very complicated and messy world. We would like everything to be reducible to a bumper sticker or sound bite but, as William James reminds us, “Nature is not bound to satisfy our presuppositions. In the great boarding house of nature, the cakes and the butter and the syrup seldom come out so even and leave the plates so clean.”

The moral aspects of teaching often begin with resisting the temptation to deliver a product, to give the customer what she wants. Sometimes, Maria Popova suggests, what people want is the last thing they should get.

Giving people what they want isn’t nearly as powerful as teaching people what they need. There’s always a shortcut available, a way to be a little more ironic, cheaper, more instantly understandable. There’s the chance to play into our desire to be entertained and distracted regardless of the cost. Most of all, there’s the temptation to encourage people to be selfish, afraid, and angry. Or you can dig in, take your time, and invest in a process that helps people see what they truly need.

I try to focus on the importance of “digging in” every time I’m in the classroom. But observing myself outside of the classroom, I find that I have a lot of work to do. I spend time on Twitter, even though communicating in 240 characters or less is hardly an example of in-depth discourse. I quickly block or unfriend Facebook people who clearly hold political views that are radically different from mine. I bristle when someone challenges me in the “Comments” section of this blog. Consider for instance, this comment posted two days ago in response to one of my recent essays:

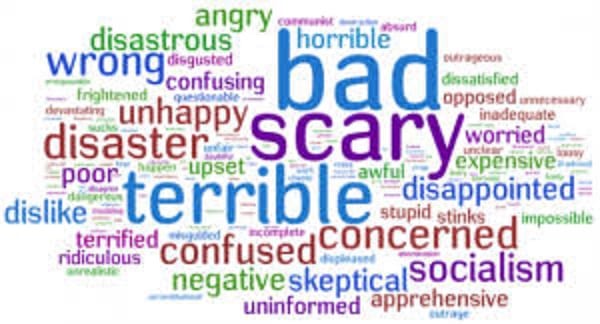

We all have to examine our worldviews. But frankly Trump once again seems the lesser of two evils. On one hand we have a spectrum of ignorant Marxist solutions, questionable support for infanticide, an inability to discern between legal vs. illegal immigration, and climate change alarmism. On the other side we have a bloviator who supports capitalism, strong defense, and America first solutions. Lesser of two evils indeed.

This goes beyond “trigger words”—for me, this is a “trigger comment.” My immediate thought was to ignore the comment and block the commenter. My second thought was to craft a snarky response intended to blow him/her out of the virtual water.

But then I thought a third time. If I am going to call for moral maturity in thinking and learning, that maturation process begins with me. And that means moving beyond being triggered by people and ideas that make me uncomfortable because they are so different than mine. And the work begins . . .