The first draft of my first sabbatical book project is completed, minus the introduction and conclusion. As several trusted friends and family members read the draft and provide their insights, I am revisiting any number of essays from the past that I’m sure will inform the introduction to the book in which I will be providing a brief (hopefully) overview of my religious pedigree. One of the less attractive aspects of this upbringing was Bible camp.

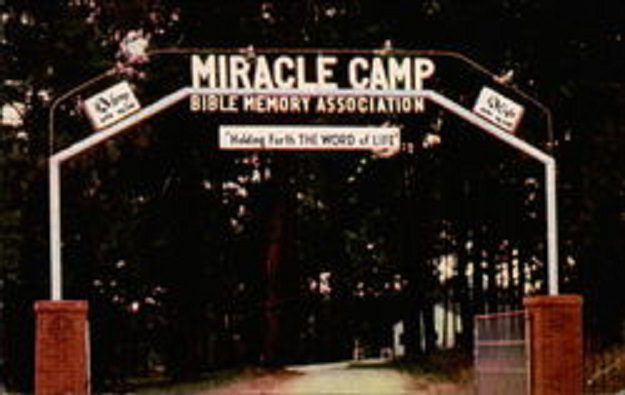

I was the world’s most pathetic camper. One of the (alleged) rewards for 12-15 weeks of learning Bible verses throughout the winter was the privilege of attending BMA (Bible Memory Association) camp for a week in the summer; I earned this reward for what must have been 7-8 years running when I was young, starting when I was about eight years old.

And I hated camp. If you use your imagination a bit, you can probably picture why camp for a bunch of fundamentalist-raised youngsters wasn’t particularly fabulous. Reveille at 6:00 in the morning, church before breakfast, Bible study in the morning, enforced nap time after lunch (I’m not kidding), “free time” for two or three hours in the afternoon which included same-sex swimming (I am a lousy swimmer), paddle boats which invariably broke down in the middle of the lake, and horse riding (I was deathly afraid of horses). Devotions between supper and the evening worship service, during which we were required to hunker down somewhere with our Bibles by ourselves for half an hour, then evening service for a couple of hours, then taps and lights out by 9:45. What fun.

Truth be told, I would have hated any camp, Bible Memory Association or not. I suffered from debilitating and close-to-terminal homesickness. I usually went to camp with my brother and two or three cousins while my parents spent the week at a Bible conference about 75 miles away where my father was the featured speaker. I would much rather have stayed with them (with my mother, actually), but off to camp I went every year. I usually spent the first twenty-four hours crying or at least sniffling—I remember one year my camp dorm counselor, who was not much more than a kid himself, was assigned to spend the first afternoon of camp trying to console this skinny, curly-headed kid who wanted his mother. He probably asked for a raise after that.

What I didn’t understand is why no one else appeared to be homesick. I usually saw two or three like-minded campers sniffling and with tears in their eyes the first day or so, but the vast majority of the upward of 200 campers not only seemed fine, but appeared positively thrilled to be away from their mothers. Go figure. To their credit, my non-homesick brother and cousins always managed to put up with me without calling me a pussy (or whatever good Baptist kids would have called someone like me). They just waited me out—I wasn’t going anywhere, after all.

I was deeply moved when I read the following lines in a Rainer Maria Rilke poem not long ago:

I love you, gentlest of Ways,

Who ripened us as we wrestled with you.

You, the great homesickness we could never shake off.

You, the forest that always surrounded us.

“The great homesickness we could never shake off.” That’s one of the best names for God I’ve ever encountered. Homesickness cannot be cured by anything other than the presence of what you are homesick for. Sure, I was able to cope at camp and sort of enjoy myself at times, but there was always a gnawing emptiness, a low-grade disturbance, that I knew would not leave until I saw my parents’ car driving through the front gates of camp on Saturday morning. I never made the connection until I read the lines from Rilke, but the Psalmist is homesick when he writes:

As the deer pants for the water brooks,

So pants my soul for You, O God.

My soul thirsts for God, for the living God.

When shall I come and appear before God?

And Rilke gets it exactly right in another poem when he writes:

I am orphaned

each time the sun goes down.

I can feel cast out from everything.

That’s when I want you—

you knower of my emptiness,

you unspeaking partner to my sorrow—

that’s when I need you, God, like food.

Just as there were some campers who weren’t homesick for their mothers, I suppose there are some people who don’t thirst for God. But I do.

I recall the Holy Week services at St. John’s Abbey during my sabbatical over a decade ago in Collegeville, MN. The Abbott’s Palm Sunday homily focused not on Judas, or on the donkey, or the Pharisees, or Pilate, or Peter’s denial, but on the first event in Mark’s telling of the Passion story—the woman who pours the costly oil on Jesus’ feet.

The Abbott was trained as a chemist, so he spent a few minutes describing just why nard, a precious oil squeezed from the roots of the spikenard plant which grows only at the foot of the Himalayas, and alabaster, the translucent stone from which the broken flask containing the nard was made, were so expensive. Not surprisingly, the disciples and others are appalled at the waste—the oil and the flask could have been sold for more than a laborer’s yearly wage. A lot of poor people could have been helped.

And they are right. But the woman knows something the onlookers don’t know. She recognizes Jesus in a way that others who had spent months and even years with him don’t. The Gospels tell us that the disciples were often confused about who Jesus was. But by anointing Jesus, the woman is saying “I recognize you. I know you who you are. I’ve been homesick for you my whole life, and I’ve found you. I’m home.”

I yearn to belong to something, to be contained

in an all-embracing love that sees me

as a single thing.

I yearn to be held in the great hands of your heart—

oh let them take me now.

Into them I place these fragments, my life,

and you, God—spend them however you want.