I asked my Facebook friends at the beginning of the summer to list three or four books that changed their lives. Not necessarily books that belong in the Great Books curriculum, but books that came just at the right time and spoke to them in a particular and memorable way. I’ve written about two of mine over the past couple of months–here’s another one.

A year from now, I will be on sabbatical for the Fall 2023 semester (the fourth, and perhaps final, sabbatical of my career). It’s hard to believe, given the way that time flies, but fifteen years ago I was in exactly the same situation—a sabbatical semester (the second of my career) on the horizon. During my first sabbatical, all the way back in 2002, I didn’t go anywhere; instead, I holed up in my office and wrote the first draft of an academic book that was published two years later. As I began to think about my second sabbatical, I knew that I wanted to go somewhere for at least part of the semester (that’s what normal academics on sabbatical do), but my career has been shaped to fit the campus where I have now taught for twenty-eight years. I didn’t even know where to begin.

A few months earlier I had picked up a book called The Cloister Walk while wandering around Borders. I liked the picture on the cover, which announced that the book was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year and contained the following review excerpt from The Boston Globe:

This is a strange and beautiful book . . . If read with humility and attention, Kathleen Norris’s book becomes lectio divina, or holy reading.

This is a strange and beautiful book . . . If read with humility and attention, Kathleen Norris’s book becomes lectio divina, or holy reading.

The Cloister Walk became my bedtime reading—a book that defies description or summary. Following Norris’s quirky faith through the liturgical year was both strange and beautiful just as the NYT reviewer promised; as another reviewer wrote, “she writes about religion with the imagination of a poet.” I had no idea before I picked the book up that this was exactly what some unknown part of me had been looking for, nor did I know that on a practical level it would point me toward where I would spend my sabbatical semester a year later.

Kathleen’s experiences that frame The Cloister Walk occurred during two separate residencies at the Collegeville Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Research on the campus of St. John’s University in Collegeville, Minnesota. While there, she immersed herself in the daily Liturgy of the Hours with the Benedictine monks at St. John’s Abbey about a ten minute hike up the hill to campus. She writes that the Benedictines refer to their daily office as “the sanctification of time.” The Cloister Walk is the fruit of that liturgical immersion—a “strange and beautiful book” written by a woman who I would come to know as equally strange and beautiful. As I read, I unexpectedly resonated with the eclectic spiritual vision of a fellow traveler steeped in the Protestant tradition as I am—except that she was strangely attracted to the Benedictines and their ancient Rule.

An important aspect of monastic life has been described as “attentive waiting.” A spark is struck; an event inscribed with a message—this is important, pay attention—and a poet scatters a few words like seeds in a notebook.

Kathleen describes in The Cloister Walk the frustration that her fellow resident scholars at the Institute felt with the poetic and decidedly non-academic energies she brought to their collective work, a frustration that I must confess I as an academic also occasionally felt when wandering through the intuitively organized labyrinth of her book. But then, those who seek God must learn that there are as many paths to the divine as there are persons seeking a path.

When it comes to faith . . . there is no one right way to do it. Flannery O’Connor once wisely remarked that “most of us come to the church by a means the church does not allow,” and Martin Buber implies that discovering that means might constitute our life’s work. He states that “All [of us] have access to God, but each has a different access. God’s all-inclusiveness manifests itself in the infinite multiplicity of the ways that lead to him, each of which is open to one [person].”

I had no idea at the time just how badly I needed to hear that. On a deep level I had ceased hoping to find my unique spiritual path over the years, weary of running head on into what a monk described to Kathleen as “the well-worn idol named ‘but we’ve never done it that way before!’ And people wonder how dogmas get started!”

At the time I did not trust my ability to hear a possible word from God—I entirely relied on my intuitively and spiritually attuned wife to do that for me. But as I worked my way through The Cloister Walk I realized that something more than my usual resonance with a fine writer’s craft was going on—I wanted what she was writing about. Literally. I contacted the Collegeville Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Research and applied to be a resident scholar for my sabbatical semester during the first five months of 2009. They accepted me.

On the day that Barack Obama was inaugurated as our 44th President, a crystal clear Minnesota January day with a high temperature of zero degrees, I found myself in a tiny apartment situated in the very same complex on the shores of the very same lake I had read about eighteen months earlier. What on earth was I doing here away from Jeanne and my dachshund Frieda, all alone surrounded by a bunch of people I didn’t know? The only good answer was that I wanted what I had read about. And the rest is (my recent) history.

On the day that Barack Obama was inaugurated as our 44th President, a crystal clear Minnesota January day with a high temperature of zero degrees, I found myself in a tiny apartment situated in the very same complex on the shores of the very same lake I had read about eighteen months earlier. What on earth was I doing here away from Jeanne and my dachshund Frieda, all alone surrounded by a bunch of people I didn’t know? The only good answer was that I wanted what I had read about. And the rest is (my recent) history.

Professionally, what I carried from that sabbatical was a new way of writing (that three years later turned into this blog) and a bunch of academic essays that were never published (because I never sent them out). But I was changed from the inside out. While at Collegeville, I immediately tested the waters of daily noon prayer with the monks up the hill at the Abbey, a commitment that within a few weeks became a three-times-a-day habit. The prayers were important, but inhabiting the Psalms as a collective body opened a “deepest me” space that I have come to recognize as the place where the divine in me hangs out. Every possible human emotion and every possible encounter with the divine is in those ancient poems.

[The Psalms’] true theme is a desire for the holy that, whatever form it takes, seems to be a part of the human condition, a desire easily forgotten in the pull and tug of daily life, where groans of despair can predominate.

One day at noon prayer, one of my friends from the Institute directed my attention toward the row behind us. “That’s Kathleen Norris!” my friend whispered in a slightly too-loud-for-noon-prayer voice. That evening Kathleen—on campus for a university board meeting—visited the Institute for dinner. For the current Resident Scholars, it was like a visit from the Beatles. Like any groupie, I made sure Kathleen signed my copies of her books (I had them all in my apartment) and we spent three or four minutes in one-on-one conversation (which I was sure she would not remember). But just meeting the person whose book had brought me to this wonderful place in the middle of nowhere was enough.

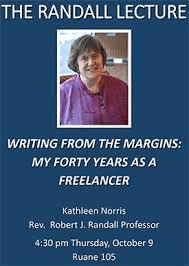

A year and a half later, while I was back in Collegeville for a writer’s workshop at the Institute. Unexpectedly, Kathleen and I were both staying at the Abbey Guesthouse (she was not part of the workshop–I forget why she was on campus).  We had several breakfasts and lunches together, enjoyed some conversation on the guesthouse patio overlooking the lake, and a friendship was formed. I particularly enjoyed the envious looks on my workshop colleagues’ faces when they observed me lunching with a world-famous author in the cafeteria one day. Several years later, Kathleen was an endowed scholar on campus for an academic year and inhabited the office across the hall from me. I’m proud to say that I’m the one who suggested her to the scholar-in-residence selection committee.

We had several breakfasts and lunches together, enjoyed some conversation on the guesthouse patio overlooking the lake, and a friendship was formed. I particularly enjoyed the envious looks on my workshop colleagues’ faces when they observed me lunching with a world-famous author in the cafeteria one day. Several years later, Kathleen was an endowed scholar on campus for an academic year and inhabited the office across the hall from me. I’m proud to say that I’m the one who suggested her to the scholar-in-residence selection committee.

For my birthday during that academic year, Jeanne and I took Kathleen out to dinner—she’s a great conversationalist and we had a wonderful time. It’s strange how things work out. In August just just a few days before the beginning of that new academic year, I was sitting in the atrium of our student center minding my own business when I heard a voice from the stairs behind me—“I know you!” It was Kathleen. “And I know you too,” I thought. “You wrote the book that changed my life.”