RMy baseline criterion for whether a particular class has gone well is to answer the question “Did I learn something new today?” in the affirmative. By that standard I have had a number of excellent classes in my Montaigne honors colloquium this semester. Michel de Montaigne frequently writes about how much hubris and pride it requires for mere human beings to claim anything with certainty about the personality traits and preferences of God, as in this passage from one of his essays:

What is more vain than to try to divine God by our analogies and conjectures, to regulate him and the world by our capacity and our laws, and to use at the expense of the Deity this little shred of ability that he was pleased to allot to our natural condition? And, because we cannot stretch our vision as far as his glorious throne, to have brought him here below to our corruption and our miseries?

Later in the same essay he continues in this vein:

It has always seemed to me that for a Christian this sort of talk is full of indiscretion and irreverence: “God cannot die, God cannot go back on his word, God cannot do this or that.” I do not think it is good to confine him thus under the laws of our speech. And the probability that appears to us in these propositions should be expressed more reverently and religiously.

Most of my nine students in this colloquium are from a Catholic background as are the majority of students at my college. Some of them describe themselves as committed Catholics while others say they are currently questioning the faith they were raised in. In the middle of an excellent conversation about the above and related passages from Montaigne, one young woman observed that “it seems a bit inconsistent for Montaigne to argue that we have no basis on which to say anything about God with certainty while at the same time using male pronouns to refer to God as if he knows for sure that God is a dude.”

Boom! My student made an excellent point. Although we might be willing to give 16th century Montaigne a pass for referring to the divine with male pronouns, might not 21st century persons of faith do better? I have sought for years to avoid gender-specific pronouns in my writing, including reference to God; “What is greater than us,” “the Divine,” and simply “God” need not be gender-specific. To press the envelope, I frequently refer to the Holy Spirit as “She,” even more often refer to her as “Big Bird” in honor of Jeanne’s favored moniker for the HS. And I greatly enjoyed William P. Young’s choice in his 2007 book The Shack to portray the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as a large African-American woman, a middle-eastern guy with brown skin, and an Asian woman.

But old habits are hard to break. Over the past few years the liturgy in the Episcopal church has become less and less gender specific, often changing pronouns that have been in place for centuries. The little internal twinge I experienced the first time the lines late in the Nicene Creed referring to the Holy Spirit changed from

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of Life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son; with the Father and Son He is worshipped and glorified; He has spoken through the prophets . . .

to

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of Life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son; who with the Father and Son is worshipped and glorified; who has spoken through the prophets . . .

When they changed the end of the Sanctus from “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord” to “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord,” that was going too far! Now I have to actually look at these texts in the bulletin as we say them together rather than mindlessly parroting them as I have for decades! Suffice it to say that pronoun changes can still be an issue for someone who has been working on them for years.

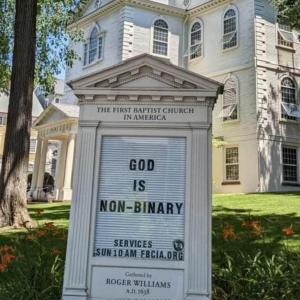

My student’s observation about assuming that God is a dude reminded me of something both striking and shocking that I came across on Facebook last month.

I suppose that “God is Trans” might have been more provocative, but not much. First, note the church in question. Thousands of towns in this country have a “First Baptist Church,” simply the first Baptist church to show up in that town historically (followed frequently by “Second Baptist” and so on). But there is only one “First Baptist Church in America,” and it is located downtown in my city of Providence, Rhode Island.

Notice what the sign says at the bottom: “Gathered by Roger Williams A.D. 1638.” Roger Williams founded the colony of Rhode Island after being thrown out of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to the north as a heretic for believing and preaching such uncomfortable truths as that indigenous people need not convert to Christianity to go to heaven, but need simply to follow their own religious traditions faithfully. The church he founded is the first Baptist church founded in America—hence its name. Providence has been a place for outsiders and rejects ever since its founding.

Persons who identify as “non-binary,” among other things, reject the gender binary that all people are one of two genders, female or male, woman or man. A non-binary person simply rejects this either/or binary. Although there are many pronouns that a non-binary person might prefer others to use when referring to them, one possible way is with the pronouns “they/them/their” rather than the traditional “he/him/his” or “she/her/hers.” The matter of appropriate pronouns is, of course, politically and socially charged—an issue that I do not choose to jump into here other than to clearly state that the appropriate referring pronouns for a person are for that person to choose and specify, not someone else. I might also add that even with this commitment, I find the use of chosen pronouns to be challenging, simply because I am a late baby boomer and old habits die hard.

At the risk of being controversial (which has never stopped me before), I’m inclined to think that if one cannot avoid referring to what is greater than us with pronouns, “they, them, theirs” is more appropriate than traditional binary options. After all, the sacred texts themselves are not particularly helpful here. God is frequently referred to with plural nouns in the Hebrew scriptures, and some of the names for God are feminine. “They” also seems to catch something important when considering the Trinity.

Our traditional choice to refer to what is greater than us as if God is male is a choice fashioned by patriarchal culture and hierarchy more than by the text. Insisting that God must fit into our traditional and familiar human gender categories is a striking example of what Montaigne is warning against. This example is particularly striking when we come to realize that these gender binary terms don’t even satisfactorily describe the complexities of human experience, let alone what is greater than us.

The marquee sign in front the First Baptist Church in America last month is both deliberately controversial and an important reminder that when speaking of what is greater than us, we cannot confidently assume that our limited language is ever complete or even partially correct. The next time you are tempted to refer to God within traditional language categories, try something different. Try “Parent, Sibling, and Advocate” for the Trinity. Try “that which is greater than us” or “the Divine.” Or try “They/Them/Theirs.” I dare you.