I detect that a rebellion against all things “religious” is growing on me. Often it amounts to an instinctive horror. Dietrich Bonhoeffer

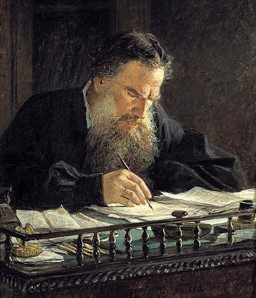

Not long ago I had the opportunity to use Leo Tolstoy’s Confessions in class for the first time. There are many passages worthy of discussion in Tolstoy’s spiritual memoir, none more important than when, toward the end of his story, he describes his frustration when he discovers that members and clergy of the Orthodox Church that he has recently embraced are far more certain and judgmental concerning their beliefs and doctrines than he believes is warranted.

Tolstoy describes that during his journey toward faith, he met many believers of different faith commitments, people “of the highest moral character” to whom he wanted to “be a brother” even though some of their doctrinal positions were different that those of the Orthodox Church. To his great disappointment,

The doctrine that had promised me a union with all through love and a single faith was the very doctrine that, in the mouths of its finest adherents, told me that all these people were living in a lie . . . and that we alone are in possession of the only truth possible.

Reflecting on the often judgmental nature of persons of faith toward all those who believe differently even in the slightest way, Tolstoy observes that the assertion that you live in a lie while I live in the truth is the most cruel thing one person can say to another. I’m going to use that one the next time someone accuses me of being a heretic who is headed to hell for referring to the Holy Spirit as “She” (or some equally egregious perceived doctrinal misstep).

My students and I frequently discuss the dangers of moral certainty in any number of my classes. For many of them, this begins as a counter-intuitive conversation, given that moral principles are commonly thought to be only as good as they can be proved to be universally applicable and unassailable. Why wouldn’t we want certainty in our moral beliefs? one might ask.

At the same time, my students know that many of the worst atrocities in human history have been done in the name of various claims to certainty. The Holocaust. The Crusades. Terrorism of all sorts. Simon Critchley writes that “Human knowledge is personal and responsible, an unending adventure at the edge of uncertainty. Insisting on certainty leads ineluctably to arrogance and dogma based on ignorance.”

Nowhere is certainty more problematic than in the life of faith. Poet Christian Wiman once said in an interview that

Doubt is so woven in with what I think of as faith that it can’t be separated. I am convinced that the same God that might call me to sing of God at one time might call me at another to sing of godlessness. Sometimes when I think of all of this energy that’s going on, all of these different people trying to find some way of naming and sharing their belief, I think it may be the case that God calls some people to unbelief in order that faith can take new forms.

If my own experiences and struggles with faith are at all typical, Wiman is on to something. There are times when I find it very difficult to tell the difference between faith in God and faith in a figment of my imagination. Those are the times when, as Simone Weil provocatively wrote, atheism can serve as a purification.

This is not an unusual idea. For centuries, voices from within the camp of Christianity have called for something sounding very close to atheism. Meister Eckhart wrote that “We pray to God in order to be free of God,” from his prison cell Dietrich Bonhoeffer predicted that the future of faith would be found in what others described as a “religionless Christianity,” and Simone Weil wrote that “the absence of God is the most marvelous testimony of perfect love.”

In each of these instances, the person of faith is asked to move beyond the traditional notion of God as something outside ourselves, a picture of the divine that for many has lost its meaning. I often find myself thinking, as I listen to various descriptions of God being thrown around in different venues, that “if that was what God amounted to, I would be an atheist.” This is where the passage from Christian Wiman quoted earlier comes in. The only way for faith to evolve and take new forms is for old models and paradigms to change. As Wiman writes in My Bright Abyss, “This is why every sirgle expression of faith is provisional—because life carries us always forward to a place where the faith we’d fought so hard to articulate to ourselves must now be reformulated, and because faith in God is, finally, faith in change.”

This can be very disconcerting, because old paradigms change only with great difficulty. When life gets even more challenging than usual, the person of faith is often tempted to fall back on “tried and true” methods of getting the divine’s attention. More prayer, more church attendance—but there comes a time when such methods are regularly met with deafening silence. This silence can lead either to a deepening crisis of faith or an entirely new faith altogether, a new faith that is infused with healthy doubt, and an openness to possibilities from sources that one never even considered as places where truth might reside. Wiman again:

To say that one must live in uncertainty doesn’t begin to get at the tenuous, precarious nature of faith. The minute you begin to speak with certitude about God, he is gone. We praise people for having strong faith, but strength is only one part of that physical metaphor: one also needs flexibility.

A mature faith is one that is both strong enough to look for God in places that have traditionally been off-limits and honest enough to realize that certainty is the greatest threat to faith of all.

One of the traditionally strongest arguments from atheists against belief in God is particularly effective against a supposed God who lives outside the reach of human investigation, effectively immune from supporting evidence and critical argumentation. When non-theists mock disagreements among religious folks as simply being various competitions about whose imaginary friend is better, it is this sort of God whose existence is being questioned.

An evolving faith, however, tends to move from the “out there” model to the “right here” or “in here” model when looking for the divine. If God’s immanence is at least as important as God’s transcendence, then we should expect to find glimmers and traces of the divine in the most mundane features of reality, although it takes a great deal of patience and imagination to perceive these traces. Persons of all faiths, in moments of doubt and uncertainty, can honestly share their faith experiences without the burden and bondage of doctrine and dogma, since in the trenches of faith, pristinely certain articles of faith tend to be irrelevant and meaningless. And atheists can join in the conversation, because trying to live a life of meaning and purpose without a safety net is a challenge for all of us, regardless of whether God is or is not a piece of the puzzle.

Faith steals upon you like dew: some days you wake and it is there. And like dew, it gets burned off in the rising sun of anxieties, ambitions, distractions. Christian Wiman