One of the most important tasks that an author has to face when a book is in the late stages of the publication process is the dedication. This usually happens late in the process, when your editor is hard at work making your prose more readable, the marketing people are asking you to fill out forms that include contact information for acquaintances and colleagues who might not be too embarrassed to write a blurb, and you have finally realized that this thing is actually going to be in print in a matter of months.

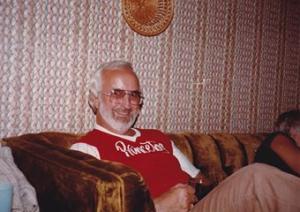

My current book–“Prayer for People Who Don’t Believe in God”–is in my editor’s hands as I write, so its dedication has been on my mind. I have dedicated previous books to my mother, to my sons, and to Jeanne—this one’s going to be for my father. It makes sense, because in many ways this is my most controversial book, pushing the envelope of traditional thinking, belief, and practice concerning prayer as far as I can. I’ve thought of him often during the writing process; the dedication is going to say something like this:

In memory of my father,

DR. BRUCE L. MORGAN

You taught me to think, to question, to explore, to doubt . . .

and only then to believe.

As Father’s Day approaches, I find myself reminiscing about just how much I owe to this man who, as all human beings are, was a complicated mixture of elements that, considered separately, don’t usually go together. He was a Baptist minister as well as an iconoclast. He was a loving parent who could be scary as hell. He was a loving husband who expected my mother to wait on him hand and foot. He often was hilarious, was a dynamic public speaker, could entertain a crowd effortlessly, yet was equally capable of withdrawing into a shell of silence and introversion like a turtle. And he had a powerful intellect, an insatiable curiosity, and an surprising ability to challenge even the most core tenets of his faith—all of which he used in direct service to the God he worshiped, who is undoubtedly as interesting and inscrutable as my father was.

And he had a powerful intellect, an insatiable curiosity, and an surprising ability to challenge even the most core tenets of his faith—all of which he used in direct service to the God he worshiped, who is undoubtedly as interesting and inscrutable as my father was.

My father was an autodidact, a learned man with little formal education beyond high school (the “Dr.” before his name was an honorary Doctor of Divinity given to him by a now-defunct seminary). He was a voracious reader of eclectic materials, usually books with God and spirituality at their center of gravity. He often was reading a half-dozen or more books at once, all stuffed into a briefcase that could barely hold the strain. During the times he was home, a regular part of his schedule would be to take off in the dim light before sunrise in the car on his way to a three or four-hour breakfast at one of the many favorite greasy-spoon breakfast establishments within a fifty-mile radius.

While at breakfast, he would spread his reading materials in a semicircle around the plate containing whatever he was eating, and indulge in the smorgasbord of spiritual delights in front of him. He used colored pencils from a 12-pencil box to mark his books heavily with hieroglyphics and scribblings that were both wondrous and baffling. It was not until I was going through some of his daily notebooks a few weeks after he died several years ago that I came across the Rosetta key to his method.

Dad often would marvel, either to the family or (more often) to his “groupies” listening in rapt attention during a “time of ministry,” at the wonders of watching God take bits and pieces of text, fragments from seemingly unrelated books, and weave them together into an unexpected yet glorious tapestry of brilliance and insight. God, mind you, was doing the weaving—Dad’s role apparently was to spread the books in front of him and simply sit back and see what percolated to the top, in an alchemical or Ouija-board fashion. God, reportedly, did stuff for Dad all the time. God even told Dad where to go for breakfast and what to order. This, for a son who had never heard God say anything to him directly, was both impressive and intimidating.

From my father I have inherited a voracious appetite for books, which is a good thing. Once several years ago, in the middle of an eye exam my new ophthalmologist asked me “do you read very much?” Laughing, I answered “I read for a living!” Actually, it’s worse than that. I recall that in the early years of our marriage Jeanne said that I don’t need human friends, because books are my friends. At the time she meant it as a criticism; now, more than thirty years later, she would probably say the same thing but just as a descriptive observation, not as a challenge to change. Just in case you’re wondering, over time I have become Jeanne’s book procurer and have turned a vivacious, extroverted people person into someone who, with the right book, can disappear into a cocoon for hours or even days. Score one for the introverts.

But Jeanne was right—I take great delight in the written word. I’ve always been shamelessly profligate in what I read. My idea of a good time, extended over several days or weeks, is to read whatever happens to come my way along with what I’m already reading, just for the fun of it. As one of my favorite philosophers wrote, “it’s a matter of reading texts in the light of other texts, people, obsessions, bits of information, or what have you, and then seeing what happens.”

I have no doubt that I inherited the elements of all of this from my father, who both in word and practice taught me that belief should be informed by hard intellectual and spiritual work—it should not be accepted unquestioningly from any authority. My bibliophilic ways sound a lot like what my father was doing at breakfast. I’ll go even further and admit that, despite the spookiness of Dad’s claim that God wove disparate texts together for him into a tapestry of inspiration and insight, I know something about that tapestry.

How else to explain the threads with which I connect Simone Weil, George Eliot, Fyodor Dostoevsky and William James through Anne Lamott, Friedrich Nietzsche, Aristotle, and P. D. James to Ludwig Wittgenstein, Annie Dillard, the second Isaiah, and Daniel Dennett? How to explain that an essay by the dedicated and eloquent atheist Richard Rorty provides me with just the right idea to organize a big project about spiritual hunger and searching for God? How to explain that a novel by an author I never heard of, which Jeanne bought for herself but passed on to me instead (“I think this is your kind of book”), was so full of beautiful characters and passages directly connected to what I’m working on that it brought chills to my spine and tears to my eyes? Is God weaving tapestries for me too?

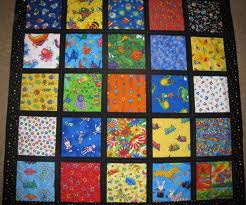

Maybe. But I think a different sort of textile is being made. The process of throwing texts together and seeing what happens is not really like weaving a seamless tapestry at all. It’s more like sewing together a very large, elaborate, polychrome quilt in which the pieces and patches can be attached, separated, contrasted, compared, in the expectation that something unusual and exciting just might emerge.

Why can’t Freud and Anselm have a conversation with each other? Why can’t Aquinas and Richard Dawkins get into a real debate without knowing ahead of time who is supposed to or has to win? In The Waste Land, T. S. Eliot writes “these fragments have I shored against my ruin.” I’ve never liked that, since it sounds as if T. S. can’t think of anything better to do with the pieces of stuff lying around the wasteland than to use them as props shoring up his wobbly whatevers. He should have tried making a quilt.

I suspect that the transcendent makes many demands on us, most of which we have only fuzzy intimations of. This one I’m pretty sure of, though: truth is made, not found. The divine emerges from human creative activities in ways we’ll never recognize if we insist that God must be found as a finished product. As a wise person once wrote, “The world is not given to us ‘on a plate,’ it is given to us as a creative task.” I have my father to thank for giving me the basic tools for that task.