One of the teaching teammates I have taught with for the last half-dozen years is a Victorian literature scholar. This, of course, includes Charles Dickens. Her choice from Dickens for the syllabus often is the über-familiar A Christmas Carol; she gave two lectures on this text earlier this week. A Christmas Carol in late September/early October might seem anachronistic, but the text is about far more than a particular time of year. Its moral themes are both timeless and remarkably contemporary.

This novella, novella is so iconic and is such a staple of our cultural heritage that I did not expect to find much that was new in the text the first time I heard my colleague lecture on it several years ago. I was wrong. In retrospect, I realize that my “familiarity” with Dickens’ story was largely dependent on the various movie versions, as well as stage productions (one of our local theaters stages A Christmas Carol every December), that I have seen over the years. I probably had not actually read the actual text since my high school years.

Although I am thoroughly familiar with the highlights of the narrative (most of the movie versions are reasonably faithful to the original), there were a number of textual nuances that were new to me—including a two-page exchange between the Ghost of Christmas Present and Ebenezer Scrooge halfway through the text that is directly relevant to the ways in which we tend twist not only the Christmas season, but also the heart of Christianity, to fit our own proclivities and preconceptions.

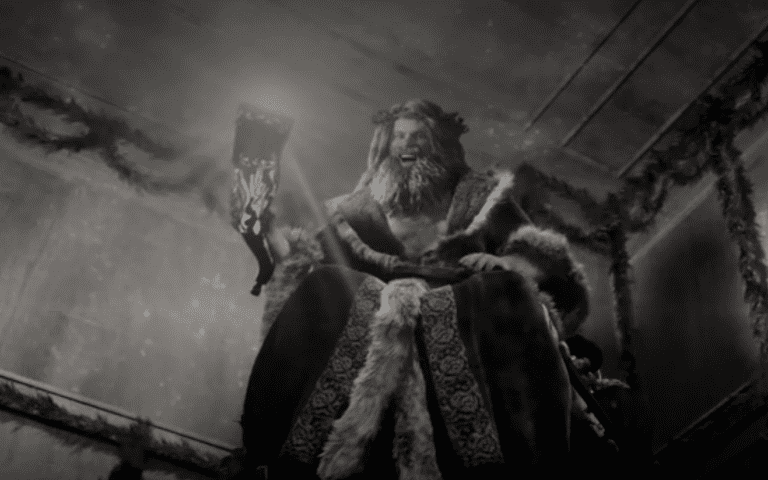

If you know the story, you’ll remember that the Ghost of Christmas Present is literally larger than life. Described as a “jolly Giant, glorious to see,” the Ghost—after confirming that Scrooge has “never seen the like of me before”—tells Scrooge that he has more than eighteen hundred brothers, one (presumably) for each of the Christmases since the birth of Jesus. Although there is certainly a Christian undercurrent to much of Dickens’ tale, this particular ghost also displays a more ancient, pagan theme, a theme that continues throughout the time that Scrooge and the Ghost spend together.

As they invisibly wander the streets of London, Scrooge and the Ghost observe a great deal of Christmas morning commerce taking place. When the ringing of the church bells “called good people all to church and chapel,” the well-to-do in the streets are replaced with poorer people “carrying their dinners to the baker shops.” Domestic ovens were a rarity at the time in the homes of the working poor; most cooking was done over an open fire or on a hob beside or at the back of the fireplace. If there was a joint of meat or a large bird to be cooked for a Sunday or holiday dinner, one would take it to a local bakery, where the meat would be cooked in the ovens after the day’s bread was done.

Sundays, or holidays like Christmas, were often the only days that working folks had off from their labors; what Scrooge and the Ghost are observing was, for many, the only opportunity for people to have a decent meal and perhaps relax a bit. As people pass by, the Ghost “sprinkled incense on their dinners from his torch” in order to add to the good cheer of the day, noting to Scrooge that the poor need this encouragement most of all. Scrooge, who by this time in the tale is beginning to care a little bit about people other than himself, seizes the opportunity to take the Ghost to task.

Scrooge knows that there are “blue law” efforts in his society to, under the guise of being a good “Christian” society, close all commercial shops—including bakeries—on Sundays. Accordingly, Scrooge accuses the Ghost of hypocrisy.

I wonder that you, of all the beings in the many worlds about us, should desire to cramp these people’s opportunities of innocent enjoyment . . . You would deprive them of their means of dining every seventh day, often the only day on which they can be said to dine at all, wouldn’t you?

Scrooge wants to know how the Ghost can claim to be in favor of lifting the burden of a difficult life off the backs of the poor at least occasionally when, in the name of what Christians and Christian charity purportedly stand for, the narrow opportunities for enjoyment and relaxation are being taken away by laws requiring the closing of the very places necessary for such enjoyment and relaxation to take place.

When the Ghost vigorously denies any involvement with or support of any such planned policies, Scrooge replies that “Forgive me if I am wrong. It has been done in your name, or at least in that of your family.” This prompts the Ghost to set things straight with an observation and a piece of advice that could have been written today:

There are some upon this earth of yours who claim to know us, and who do their deeds of passion, pride, ill will, hatred, envy, bigotry, and selfishness in our name, who are as strange to us, and all our kith and kin, as if they had never lived. Remember that, and charge their doings on themselves, not us.

Dickens adds simply that “Scrooge promised that he would.” If the Ghost of Christmas Present had a microphone, this would be a “drop the mic” moment. I am reminded of something Reverend Ames says in Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead: “We human beings do real harm. History could make a stone weep.” Especially, I might add, when the harm is done in the name of God.

Those of us who claim the Christian faith are presented daily with opportunities to consider the various ways in which we—all of us, regardless of political persuasion or version of Christianity—regularly distort, twist, and often besmirch the name of the very faith we claim in ways that have nothing to do with the good news of the gospel. We all, either actively or through neglect and passivity, have been party to allowing, in the Ghost of Christmas Present’s words, “deeds of passion, pride, ill will, hatred, envy, bigotry, and selfishness [to be done] in our name.”

There is no doubt that Jesus as represented in the gospels always, without fail, aligned himself with the poor, strangers, widows, orphans, and the disenfranchised. Anyone who claims to be a follower of Jesus who does not similarly place the interests of “the least of these” front and center would not be recognizable to Jesus as a follower. Ebenezer Scrooge learned many things from the ghosts who visited him, but none more important than this: it is possible both to become aware of things one has been blind to and to change. May we all go and do likewise.