What do you do when virtually all of the evidence relevant to an important matter points toward a specific conclusion, but you strongly believe that this conclusion is wrong? We live in a cultural climate in which, for many, intuitions and feelings regularly override even the most objective collection of facts. Still, it is worth considering whether there are times in which even those who still are willing to accept the authority of objective facts over individual feelings or intuitions are justified in favoring their intuitions.

I’ve reflected on these questions and issues before,

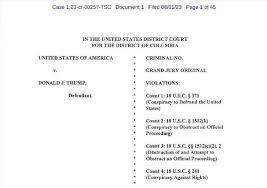

but was brought back to them anew as I read the indictment of Donald J. Trump on three counts of conspiracy and one count of obstruction that came down on August 1st. At the heart of the indictment is evidence of what former President Donald Trump was willing to do and the lengths to which he was willing to go between his defeat in the November 2020 presidential election and the beginning of Joe Biden’s presidency in January 2021 to stay in power and remain in the White House.

but was brought back to them anew as I read the indictment of Donald J. Trump on three counts of conspiracy and one count of obstruction that came down on August 1st. At the heart of the indictment is evidence of what former President Donald Trump was willing to do and the lengths to which he was willing to go between his defeat in the November 2020 presidential election and the beginning of Joe Biden’s presidency in January 2021 to stay in power and remain in the White House.

On virtually every page of the indictment, people in Trump’s circle ranging from the Vice President, senior leaders of the Justice Department, and the Director of National Intelligence to senior White House attorneys, the chief of staff, senior staffers on Trump’s 2020 re-election campaign, and dozens of federal courts told him both that he lost the 2020 election and that there was no evidence of widespread fraud in the election. The problem is that none of this lined up with what Trump wanted to believe. He believed that he had won, and he was unwilling to accept any facts or evidence that did not support his belief.

There is plenty of evidence that the former president did know that he had lost a free and fair election but chose to act otherwise in the interest of retaining power. But suppose for the sake of argument that, despite mountains of contrary facts and evidence, Donald Trump did truly believe that he had won the election and that his victory had been stolen from him because of rampant fraud. It has been suggested that this will be one of the strategies Trump’s legal team will use in court: he truly believed he had won the election and acted in ways consistent with that belief. Does such a defense have any chance of success?

The philosopher in me immediately thinks of “The Ethics of Belief,” an influential essay published by mathematician and philosopher W. K. Clifford in 1877. In our contemporary world where we say that anyone can believe and say anything they want with impunity, Clifford’s essay makes an uncomfortable suggestion: each of us is fully responsible for what we believe and each of us is morally obligated to earn the right to our beliefs by ensuring that they are supported by sufficient evidence. Clifford concludes his essay with this: It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.

Clifford begins with a brief story. A shipowner is about to send an old, well-used ship with emigrants on board across the ocean. He has reason to think that the ship needs repairs, based on his own knowledge as well as reports from the captain and crew. Yet if he puts the ship in dry dock for repairs, it will be out of service for several months, “which would put him at great expense.” In the end he convinces himself that the ship will be safe for another voyage, “trusting in Providence” and “dismiss(ing) from his mind all ungenerous suspicions about the honesty of builders and contractors.” “He watched [the ship’s] departure with a light heart . . . and he got his insurance-money when she went down in mid-ocean and told no tales.”

Does the believing shipowner bear any responsibility for the loss of life caused by the ship’s sinking? Clifford pulls no punches.

He was verily guilty of the death of those people. It is admitted that he did sincerely believe in the soundness of his ship; but the sincerity of his conviction can in no wise help him, because he had no right to believe on such evidence as was before him. He had acquired his belief not by honestly earning it in patient investigation, but by stifling his doubts. And although in the end he may have felt so sure about it that he could not think otherwise, yet inasmuch as he had knowingly and willingly worked himself into that frame of mind, he must be held responsible for it.

Applying Clifford’s analysis to Donald Trump, there are clear parallels. Just as the shipowner wants to believe that his vessel will safely cross the ocean, so also the former president wants to believe that he won the November 2020 election. Just as the shipowner is presented with clear evidence contradictory to what he wants to believe, so Trump was continually presented with evidence that, despite his belief, he lost the election. And just as the shipbuilder is responsible for the deaths of those on the ship, so Donald Trump is responsible for the actions and events that flowed from his belief, actions and events for which he has been criminally indicted and may end up in prison. Why? “Because he had no right to believe on such evidence as was before him.”

I often tell my students that in philosophy, “you have to earn the right to have an opinion.” Clifford’s claim is far stronger—you have to earn the right to believe. Clifford’s position is called evidentialism, the view that you need to let your beliefs be guided and constrained by evidence. Many critics have argued that Clifford’s version of evidentialism is too strong, primarily because it is often necessary to choose to believe something before all possible evidence can be acquired. Weaker versions say that one should be willing to revise one’s beliefs in the face of contrary evidence, or that being open to evidence is excellent and admirable. Clearly both the shipowner and Donald Trump failed both versions of evidentialism.

One could argue that beliefs by themselves are benign—one can believe anything one wants as long as the belief does not lead to actions that harm others. Jack Smith’s indictment essentially says this on its second page, allowing that Donald Trump, like every American, has the right to believe and say whatever they want (thanks, First Amendment), even when that belief and speech is patently false. Where the former president ran afoul of the law is not with what he believed and said, but with what he did as well as with what he urged and authorized others to do based on his belief.

W. K. Clifford, however, does not think that beliefs are ever benign.

No one man’s belief is in any case a private matter which concerns himself alone. Our lives are guided by that general conception of the course of things which has been created by society for social purposes. Our words, our phrases, our forms and processes and modes of thought, are common property, fashioned and perfected from age to age; an heirloom which every succeeding generation inherits as a precious deposit and a sacred trust to be handled on to the next one, not unchanged but enlarged and purified, with some clear marks of its proper handiwork. Into this, for good or ill, is woven every belief of every man who has speech of his fellows. An awful privilege, and an awful responsibility, that we should help to create the world in which posterity will live.

As the old adage goes, “be careful what you say; someone might take you seriously.” Similarly, be careful what you believe. Beliefs shape the believer and should be treated as we treat sacred objects.

In an apt analogy for today, Clifford compares the spread of fake news, bullshit, and other untruths that we find alluring to the spread of a plague:

[Our] duty is to guard ourselves from such [false] beliefs as from pestilence, which may shortly master our own body and then spread to the rest of the town. What would be thought of one who, for the sake of a sweet fruit, should deliberately run the risk of bringing a plague upon his family and his neighbors?

Clifford’s words sound idealistic and quaint in our world where the very notions of facts and truth take a regular beating in the interest of promoting what one wants to be true. A theme throughout “The Ethics of Belief” is that a society which is based on true beliefs and where citizens hold truth in high regard is cohesive, while a society where people believe on whims and base their beliefs on what’s convenient while disregarding truth is in danger of fracturing and descending into echo chambers. Our society is living confirmation of Clifford’s analysis.

At the very least, the latest indictment of Donald Trump sets in motion a process that will put many of the things we claim to cherish to the acid test. Will our democracy survive? Will any coherent understanding of truth survive? Time will tell—in the meantime, remember that your beliefs are common property and that our society is built on the assumption that everyone is equally committed to believing things that are true. Once those assumptions evaporate, what remains?