It’s taken some time for me to write anything substantial about the ten year anniversary of 9/11 (aside from one quick rant) in part because I didn’t quite know how to process much of what I was seeing and hearing. On the one hand, we saw profoundly moving memorial ceremonies and remembrances of extraordinary courage. On the other hand, we were also assailed with moral equivalence, hand-wringing, and bitter political recriminations.

I spent the better part of September 10 reading a new Christian book so vile in its anti-Americanism and historical illiteracy that I at one point literally threw it across the room (I’m not going to link to it because I would hate for anyone to actually read that dreck). I hearkened back to the Sunday after Osama bin Laden was killed when (while visiting a different church) I heard the young worship leader express regret that bin Laden had “never experienced the will of God.”

Yes he did, I thought, at the hands of Seal Team Six.

I was upset by it all, but not as much as Nancy. She literally seethed and has seethed for days. If there was ever, in our history, a moment of moral clarity, it occurred on September 11, when our enemies displayed their evil, and our fellow citizens responded with selfless sacrifice and unimaginable courage.

I was frustrated and angry until I realized something I should have realized long ago: there are really two 9/11 generations. For some of us 9/11 changed everything. It is the fulcrum upon which our entire world pivoted. For others, 9/11 was an event they saw on television, that has merely become something to talk about. The first group is tiny — representing the smallest fraction of our national population. The second group is huge and — as large as it is — is dramatically overrepresented in our pundit, professorial, pastoral classes.

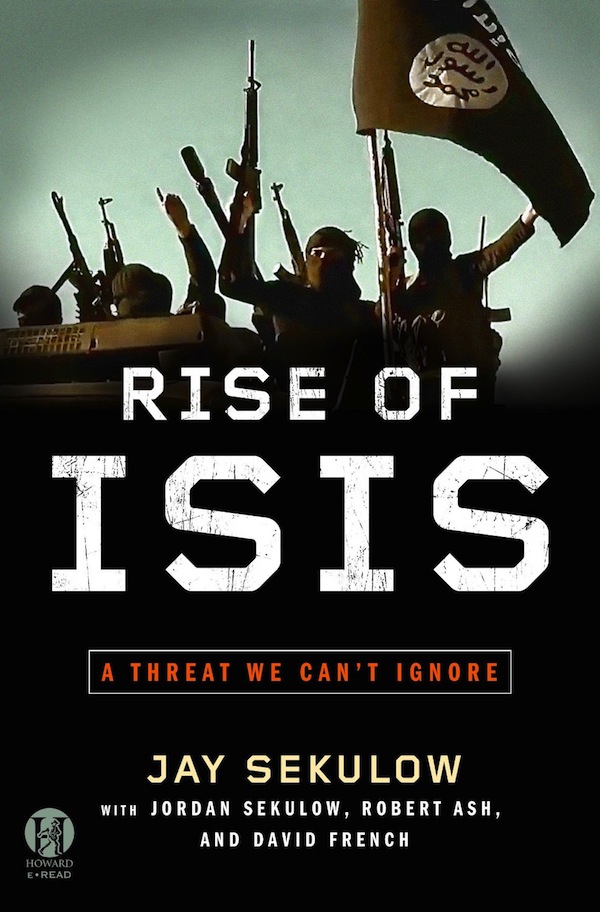

Since the morning of 9/11 roughly 10,000 Americans have died at the hands of jihadists. Up to 50,000 more have suffered wounds, some of them grievous. These are the people (and their families) most directly affected by 9/11. Moving beyond that circle are the people at Ground Zero and the Pentagon when the planes hit, the people who tasted the ash, ran for their lives, and saw the carnage. Then there’s the members of the military — some of whom have given years of their lives separated from their families “downrange” and have seen first-hand the horror of jihad in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere Finally, there are the civilian professionals who saw the evil of 9/11 and changed the course of their civilian lives, dedicating themselves to learning about the jihadist threat and fighting that threat in domestic and international legal, political, and cultural arenas.

Then there is everyone else. They have no first-hand knowledge of our enemy. They remember 9/11, to be sure (at least those over, say, 16 years old), but it is slowly becoming as relevant to their lives as Pearl Harbor, or Antietam. It’s a topic of occasional discussion, and the pressure for pundits, professors, and pastors is to have a “fresh take” or to fit the event within pre-existing frameworks. After all, they have already demonstrated — conclusively and unequivocally — that other things are more important to them, that 9/11 can and should be “boxed.” It’s just another day, really, a day that is more emotional because of its relative freshness (and because of the involvement of some of their friends and neighbors) but they acknowledge it, maybe write something about it or speak about it, then move on.

Those of us whose lives changed because of 9/11 are not a uniform group, we do not all think alike, we do not have all the same experiences, and we have wildly varying ideas about what to do (if anything) about the jihadist threat. But when we speak about jihad and our war, we have the profound advantage of experience. To us, the pundits, professors, and pastors who opine without experience — especially when they opine about an enemy they’ve never seen or met — seem somewhat like children. They just don’t know what they’re saying. They should know more, but they don’t. And — like children — they are often utterly oblivious to their own ignorance. They speak authoritatively, rashly, and sometimes stupidly.

For those of us who’ve seen the face of evil, it’s our job to educate. We’ll say different and sometimes conflicting things (you should have heard the arguments at Forward Operating Base Caldwell, during my deployment), but at this point America suffers from a deficit of influence from people who know, who’ve been there, and who’ve seen the enemy.

For the rest of the country, those who don’t know, who haven’t been there, and who haven’t seen, perhaps a bit of humility is in order. Do you really know what you’re talking about? When you’re asked to write about 9/11, about the morality of our war, or its tactics, do you understand the choices, the risks, or the pain of loss? When you’re asked to write or speak about our enemies, do you really know their beliefs, their words, or their actions? You don’t, but you act like you do.

Write what you want, say what you will, but understand that when you do, there’s a chance that one or more of your readers, one or more of your listeners, will have experienced 9/11 and its aftermath in a way that you cannot comprehend. They are likely not buying your spin or your “fresh take.” They are too busy remembering the lost, teaching children about heroes they’ll never meet, and fighting yet another nameless battle far from home.