“Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.”

– Leonard Cohen, Anthem

On Palm Sunday, we visited another parish. It was our children’s spring break from school, so we loaded a six year old and her three year old twin siblings into the van with an embarrassingly large pile of belongings, and drove to a state park with an indoor aquatic center and many outdoor activities. As spring in Indiana so often does, the temperature spanned 40 degrees over 4 days and brought us rain, sunshine, wind, and warmth. The children joined us for their first real hike in the woods – a half-mile nature trail through a wooded area. The soft, spring-mud earth pulled them in and their joy at the wonder of it all was like an awakening for us as well. On Sunday we drove through town to the local church, tucked away at the top of a hill looking out into another wooded area. This church is small, designed to look like a log cabin from the exterior. Inside, a simple, clean aesthetic with polished wood crucifix and dozens of large windows with sunlight streaming and full view of the gospel of Creation behind the altar. It’s spring, and the world is coming alive after months of quiet burial and the stillness of waiting. The earth is, quiet literally, singing and bursting out with colors, smells, and sights.

Since we are terrible Catholics remembered it was Palm Sunday, the kids stayed with grandma and grandpa (who are not Catholic) while we attended Mass. In fact, the only reason I have thoughts to share about the Passion, and betrayal, and Judas, is because I went to Mass without my kids. It’s ugly, but its true.

The Passion is a very long, spiritually rich and painful accounting. Thankfully, the priest saying Mass had the good sense to not muddy up the Gospel with his own meandering thoughts. Instead of a homily, we sat in silence for several minutes. I read back over the pages of the Gospel we had just heard and thought about betrayal and loyalty. About frail humanity and divine strength. Reflecting on the actions of key players in this story, I had one of what I jokingly call my “bad Catholic” thoughts: I feel a tremendous amount of pity for Judas. His betrayal of Jesus, yes — but what sends the shiver of terror and knot of grief to the pit of my stomach is his remorse, despair, and suicide. It all feels too familiar on some visceral level.

Judas, hard-hearted and prideful, hatched a plot to betray Jesus, allowing himself to be lured with the promise of silver. As U2 sings, “One man betrayed with a kiss” and we all know it. The kiss heard ’round the world. Yet, this is far from the only betrayal in this story, but it seems to be the one everyone remembers, tongues clucking and heads nodding vigorously, every single one of us falling over each other to tell Jesus how we would never betray him like this monster Judas.

Jesus shaking his head softly, looking at me with those eyes that send a shiver down my lying spine, because of course I would, have, did betray him. Anytime I haven’t given food to the hungry, drink to the thirsty, shelter to the homeless, clothing to the naked, welcome to the stranger, and on — I have betrayed him in his distressing guise of a suffering brother or sister. Let’s not pretend we don’t know the stakes here.

Yet, in the same Passion narrative, Jesus’ best friend and number one hand-picked to lead everybody golden boy disowns him as soon as shit gets real. Is it feeling real yet? Peter runs away and then – oh foolish, predictable flesh – denies even knowing Jesus. Not once, not twice, but three damn times. Peter did not plot, did not go behind the back of Christ as the catalyst of demise. Yet, his betrayal seems somehow less required by the churning wheels of prophesy and fate, and more the dismal failure of bravery and love — it’s more intimate because it’s a kind of betrayal we all know. The ones who love us, who sing it far and near how they will never leave us, will always be there for us. When the suffering comes, as it inevitably does — they are ghosts. Peter in essence ghosted Jesus.

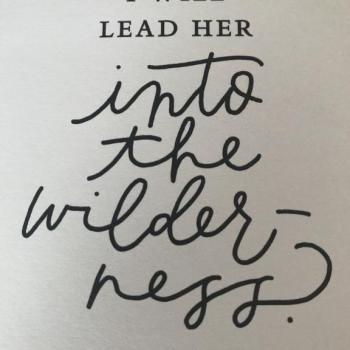

The whole thing is fallen humanity on stark display, juxtaposed with the quiet, humble, non-violence of God. In typical God fashion, the betrayal is merely the crack that lets in His light. The real tragedy here is not that Judas and Peter betrayed Christ. Betrayal is inevitable. It is the cost of free will, and God knows it well – having been one of us – an absurd and beautiful being. Peter and Judas illustrate for us the two things we can do when we abandon Christ. Judas turned inward on himself, fixating on his sin, and asking all the wrong people for forgiveness. Stumbling blindly he tried to undo his undoing, only to be rejected and cast out. The tremendous pride of Judas would not allow him to crawl back to Christ, rending heart and garments, raising tentative eyes to his warm, eternal face. To say the words, “I have sinned against heaven and against you.” Judas is paralyzed by his guilt and despair — his real betrayal is believing he could never be forgiven.

Peter is a hot-headed, impetuous fool. A fool who is wracked with sorrow and remorse after his betrayal of Christ, but who rather than turning inward, trying to glue the crack together with his own broken hands – Peter waits and prays and knows that a great reckoning is about to occur. His betrayal did not kill Christ, but it did pour salt in his wounds. Yet he is forgiven, and not only that, he remains the leader and becomes first Pope. He allowed the crack of his betrayal to be shone-through with light and he remains a witness of the power of forgiveness.

Look a bit farther into the Passion and there’s another story, this one of loyalty. It struck me on Sunday, as it always does when reading the narrative, that of everyone who followed Jesus it was the women of his ministry who remained with Him until the end. Of course they did, I always think. Wouldn’t you, if you were a woman in first century Palestine and met Jesus? Here, a man who looks you in the eye and speaks to you like a human, an equal, a woman, not a child. Here, a man who looked on their bodies and saw not a prize to be won or a problem to be solved, but sacredness and gift. Is it any wonder they risked it all and gave from their treasure to further his ministry, the hope of his truth to set them free? These women are the witness of loyalty, of those moments when grace permeates and transcends human frailty. The women faithful to Christ – Mary, Mary Magdalene, Salome, Mary, and Martha (we need to say their names) – they rang the bells they still could ring.

As we enter the Triduum, may we leave aside the perfect offering we’ve crafted in our minds and instead offer our own cracked places, made ready as they must be, for light streaming.