I grew up in the Mohawk River valley of upstate New York. By the time the long, frigid winter was over, we’d often seen more snow than anywhere in the country.

Life was rugged both inside and outdoors.

My dad was angry and drunk and hit my brother and me and crashed our family vehicles and hated his job and, I think, himself. He made pitchforks at the Union Tool Company, working in the forge, a role even the toughest guys in the factory respected. Some of them tried it for a few days for the higher pay but couldn’t hack it. My father did it for twenty-seven years. He came home with burns on his clothes and skin several times a week.

My father was an alcoholic whose own father promptly drank himself to death after causing my grandmother and their three kids to leave him for good—an event that, in 1950s working class America, was normally reserved for a profound level of misery.

One Father’s Day, when I was six or seven, my dad put me in the car but didn’t say where we were going. When we arrived at Ilion Cemetery, we got out, walked over to his father’s grave, stared at it, walked back to the car, and drove home. Not a word passed between us. That was almost thirty years ago.

In his book Poetry as Survival, Gregory Orr writes:

There’s a proverb that shows up in many cultures and goes something like this: the willow that bends in the wind survives; the oak that resists, breaks. The wisdom that underlies the personal lyric is akin to this proverb. This wisdom says: the way to survive disorder is to let it enter you, to open yourself to it, rather than resisting it or denying its power and presence.

Having something healthy to do with one’s pain is central for Orr, whose early collection, Gathering the Bones Together, deals with the accidental death of his brother. Peter Orr was eight years old when their father took them hunting and a gun that Greg was holding went off, killing Peter.

How does one “gather the bones together”—reconstitute that which is lost? It’s impossible. Orr later turned to poetry, translating experience into language. Art was a response to deep, personal pain and, as he claims, a way of surviving. He writes, “It is the initial act of surrendering to disorder that permits the ordering powers of the imagination to assert themselves.”

Writing poetry became a choice to stay alive in the long term, to achieve a form of order in the most basic and practical sense.

Poetry also helped me open myself to the disorder of my early life by exploring it imaginatively. I’ve written many poems about where and how I grew up. I even found a symbol in a strange gesture my grandparents made years ago: they planted a plum tree in the field beside their house.

One does not grow plums in Leatherstocking Country, and so that plum tree died—but not until yielding a few summers of sweet fruit as unexpected as grace. For me, the plum tree came to stand for all fragile things in a harsh place, some of which miraculously survive and even flourish.

When I first discovered the power of poetry to help me make sense of chaos, I went through a period of reading and writing for the next epiphany, hunting it down as a thrill seeker does the next rush.

Of course that’s not sustainable. Someone has said that the trouble with life is its daily-ness. Fr. Richard Rohr, OFM, points out that we cannot live at the center—that it is not our lot to experience ecstasy or beauty day after day.

But neither can we live only on the fringes of the ordinary. When we stay out there too long, we risk isolation, depression, eccentricity; we lose the human connection we need. So, Rohr says, all life is a dance between the center and the edges. Our hope, he adds, is to learn to dance more gracefully.

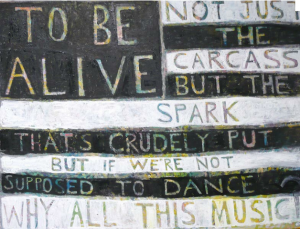

Gregory Orr’s poetry not only suggests the dance from the center to the margins but enacts it. In the mystical volume Concerning the Book that is the Body of the Beloved, Orr asks the poignant question:

To be alive: not just the carcass

But the spark.

That’s crudely put, but…

If we’re not supposed to dance,

Why all this music?

I write about my dad. I write about the plum tree. I’ve since broken the silence about my father’s father; we’ve had one or two conversations about him, which is one or two more than I had the first thirty years of my life. All of these subjects are, for me, paradoxical—a slow dance between center and margin.

To be honest, I’m not always sure which direction I’m moving in.

A few months after my first volume of poems came out, my father wrote me a short note. It said, “I read your book. You remembered everything, and you wrote it all down.”

I hate to grasp after explanation where mystery must suffice, but I wonder if his words contain a kind of recognition that disorder entered us but imagination has begun to transform it.

I’ll never know, but I know I count myself in Gregory Orr’s camp, among people for whom poetry is indeed a matter of survival. If my writing yields fruit for a season—and only enough for me, my dad, and maybe a handful of neighbors, then I will keep on. I’ll keep dancing from carcass to spark and back as long as the music plays.