This blog post is adapted from my manuscript, The Stained-Glass Kaleidoscope: Essays at Play in the Churchyard of the Mind, currently searching for a publisher.

This blog post is adapted from my manuscript, The Stained-Glass Kaleidoscope: Essays at Play in the Churchyard of the Mind, currently searching for a publisher.

As the son of a minister, I grew up on a musical diet that consisted solely of albums by Christian artists. In a way, I was the musical equivalent of a vegetarian.

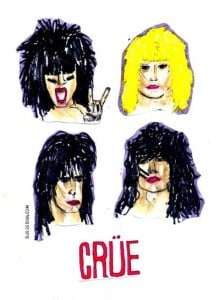

When I was in junior high, however, a high school senior at church named Brad introduced me to musical meat in the form of Mötley Crüe.

On a youth group trip, he played the band’s most accessible song, “Home Sweet Home,” for me on his Walkman as if it were a suitable bridge between L. A.’s Sunset Strip and the padded, protected world of the Christian music nursery where I slept and suckled.

To my surprise, I liked “Home Sweet Home.”

When I caught a glimpse of the band’s Shout at the Devil cassette in Brad’s backpack, however, I saw a song title I liked less: “Bastard.” As far as I knew, bastard was a seven letter four-letter-word.

I dismissed Mötley Crüe then and there, and did not think much about them again until I was twenty-six and found Mötley Crüe’s biography, The Dirt, at Borders. I thought reading it might be a fun way to challenge my previous dismissal of the band.

Having subjected the more inflexible aspects of my faith to scrutiny in therapy after my diagnosis with OCD that year, there was a little more elastic in the waistband of my theological underwear—a little more wiggle room in the worldview that informed how I lived.

By this time, I knew bastard was not necessarily profane. I could harbor Christ-like compassion for children born out of wedlock, after all. Perhaps this was what Mötley Crüe’s song had been about all along. Perhaps, like their contemporaries in Bon Jovi, the members of this band, too, were “living on a prayer.”

But there was another reason I was drawn to Mötley Crüe’s biography—a part of me wondered if I had missed out on something by living the sheltered life of a minister’s son. While the members of Mötley Crüe resembled the kind of people one might find at a homeless shelter, I knew their lives were anything but sheltered.

After reading the book, it occurred to me that it is something of a miracle—though not necessarily a God-ordained one—that the members of Mötley Crüe are alive today. Instead of going into detail about their debauchery, I will simply put it this way:

When meat processors do to beef what the members of Mötley Crüe did to their bodies, they call the end result beef jerky. (Then again, I know little about the production of beef jerky, so I could be wrong.)

While the members of the band somehow survived the wars they waged against their bodies, survival is not the only thing a person can hope for in this life. I began to wonder if the members of Mötley Crüe found meaning in their experiences.

When God saves us, perhaps God saves us from meaninglessness more than anything else. As I thought more about Mötley Crüe’s epic tale of trash and triumph, I was struck by how much it reminded me of the book of Ecclesiastes in the Bible.

It was a conclusion I never would have made in junior high.

I had been unable to move beyond the title “Bastard” on Brad’s cassette, so it never occurred to me that people might have used this word to describe Jesus.

While the Israelites knew nothing about shotguns, they probably knew a shotgun wedding when they saw one. I imagine the people Mary lived among gossiped about a bastard who, unbeknownst to them, was the Son of God—the King of Kings.

The author of Ecclesiastes was likewise a “son of David, king in Jerusalem.” He amassed the kinds of wealth and achievements that only a king could. He also had his own harem, and in this sense he was not unlike the members of Mötley Crüe.

He lived a materialist’s dream, but in the end he declared it all meaningless—a “chasing after the wind.” Throughout the book, he repeats the refrain: “Meaningless! Meaningless!” In his experience, meaning can only be found in fearing God and keeping God’s commandments.

The members of Mötley Crüe do not reach the same conclusion in The Dirt, but parallels with Ecclesiastes exist nonetheless. As the band reflects upon its experiences, it becomes apparent that there is rot beneath rock ‘n’ roll’s vainglorious veneer.

Like Qoheleth, the narrator of Ecclesiastes, the members of Mötley Crüe are wind-chasers, too. The pleasures they experience are fleeting.

As the kings of Sunset Strip, they had everything and lacked nothing. They supped at rock ‘n’ roll’s sexual smörgåsbord, snorted elephant tranquilizers, and played countless games of one-of-these-Quaaludes-is-not-like-the-other.

Despite these passing pleasures, personal pains linger. Regrets fester. The glory of the moment cannot outshine the ruin.

After reading The Dirt, I wondered if the members of Mötley Crüe might echo the author of Ecclesiastes in shouting, “Meaningless! Meaningless!”

The Dirt may be a rock ‘n’ roll memoir, but it brought me face to face with the limits of the finite pleasures we take refuge in to escape the meaninglessness of life when God eludes us. I never expected to find something sacred in something so profane.

Perhaps there is a season for reading about decadent rock ‘n’ rollers, a season for shouting at the devil, a season for consuming musical meat after years of being a vegetarian.

Illustration by Danny Joe Gibson