Near the end of Kenneth Lonergan’s film, Margaret, a seventeen-year-old girl sits next to her mother in a theater, watching a duet from Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffman.

Near the end of Kenneth Lonergan’s film, Margaret, a seventeen-year-old girl sits next to her mother in a theater, watching a duet from Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffman.

The voices of two opera singers climb toward each other from opposite sides of the stage—rising in their plaints like two vines, hoping to unite in an arch above. The girl’s attention is rapt, her face straining at the union aspired for.

But then the singers fall back, collapsing in a cascade of defeat. The voices seem to mourn their loss—not only of the other, but also of themselves, as though in this failure to join they have discovered their own transience.

At that moment, the girl in the audience breaks loose in a storm of grief. She grasps for her mother, who grasps for her, and the spectacle all around them rings to a close.

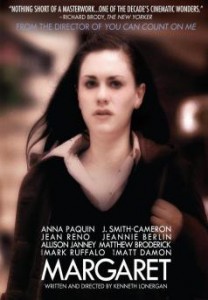

Lonergan’s meta-drama is his most ambitious task since 2000’s You Can Count on Me. His achievement lies in the intricate composite of guilt/responsibility/mortality, and of a youth’s abrupt realization of the same.

As organizing principle, he frames the tale by way of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ short poem, “Spring and Fall: To a Young Child”:

Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leaves like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! as the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you will weep and know why.

Now no matter, child, the name

Sorrow’s springs are the same.

Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

What heart heard of, ghost guessed:

It is the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.

The “Margaret” in the film is named Lisa Cohen (Anna Paquin). When first introduced, she is the kind of smart, callous Manhattan girl that masks her self-doubt by way of sharpness—quick to betray and mock.

She is cruel to admirers, short with friends, and manipulative of all. Her voice even carries an unsettling competence within it, too mature and capable, and her backstory is representative of many her age—divorced parents and free license.

Still, for all her posturing, nothing seems to give her joy; she is the kind of girl—sadly, all too common—that is above such things as joy.

But in the midst of her tense progression through life she is brought up short by a tragedy, partly of her own making. By way of her heedlessness, she is the cause of a distraction—one split-second that robs a bus driver of his attention—and a woman is killed.

From then on, nothing is the same, and the movie’s power lies in the fact that Lisa does not want it to be.

She does not so much seek consolation as she does guidance, which none can give her. Her mother, an actress, is no more mature than she; her father (a cameo by Lonergan), with whom she conducts a long-distance telephone relationship, is peculiar and awkward.

And when she shares with the dead woman’s best friend some hoped-for meaning she has read into the woman’s last words, Lisa is ferociously attacked for trying to turn the moment into a private drama.

As time passes, it is as though she seeks to find even less meaning in life, inoculating herself from present and future pain—the way we do whenever we become snide. Fear and weakness are the causes here; it takes no courage to be a sarcastic detractor.

Skepticism as a means of caution is wise, but its proper use is as a defense, not as an entire ideology. Its relative safety is achieved only by never having the guts to commit.

The peculiar truth is that life’s meaning can only reveal itself through suffering. From the Christian perspective, that is the mystery of the cross. And from that perspective, the gravity of Lisa’s suffering can be explained in terms of both the frustration that comes from not acknowledging responsibility, and the catharsis that comes from finally owning up to it.

For if there is no guilt, then the woman’s death is not tragic at all. To speak of meaninglessness is no more relevant that to speak of meaning. Indeed, of what purpose are causal chains if there is no such thing as blame? Of what purpose is conscience even?

As a girl raised in an utterly secular and cynical ethos, Lisa inartfully—and maybe in the end, inadequately—looks for the place from which making any sense of life can begin.

But perhaps even that place cannot be found in our internal meanderings through worlds of wanwood, lying leafmeal about us, unless we confront the blight we are born for: that we are clothed in a shroud, that our very skin is our winding sheet.

In Margaret, Lisa’s is the ultimate tragedy—one we all share. The sky is the proscenium arch of our great disaster—the ground, the stage of our woe. There is a chorus—fellow singers, an ensemble cast—accompanying the magnum exposition, and the flaw that any hero must be blind to, that any audience must see—is that no pose or attitude can keep us safe from the ruins amongst which we play.

For it comes, whether in glorious spring, abundant summer, or fulsome autumn. It comes in the winter of our discontent, and sometimes even in the season of our bliss.

We are never safe, and no attitude—no cut of the eyes, no smirk, no snark—will stall its procession. It is our dark birthright, and from thence springs all our woe.

But an authentic life can only begin with an awareness that we are born within the arms of our own limit, cradled within the corners of our own mortality. We need not weep for what will come. It is already here. And that fresh thought must change everything.