When my husband was told he’d have quadruple bypass surgery the next day, we were—believe it or not—overjoyed.

When my husband was told he’d have quadruple bypass surgery the next day, we were—believe it or not—overjoyed.

He’d been feeling lousy for months, and after a zillion tests the docs still couldn’t find the reason. Finally an angiogram the week after Thanksgiving showed major blockages, and we shouted halleluiah!

While he was in the hospital for the bypass surgery and recovery, I of course created an email list to keep friends and family in touch. What a joy to receive back all the good wishes, prayers of support, and offers to help—which I’ve happily taken advantage of.

A friend sat with me during the surgery, a neighbor returned our library DVDs, another neighbor did a beer run to the supermarket so my daughter-in-law could have one to unwind with after her four hundred mile drive to come help us.

George and I have been married over forty years. This past summer, as we were driving through our neighborhood of thirty-five years, I mused aloud: “We have so many wonderful connections in our town.”

George nodded: “Yes, and each one is a work of art… and takes the care of a work of art to sustain.”

How much more care, then, is required for that most long-term, intimate connection of marriage. First there’s the gradual creation of one life out of two—a new and ever-renewing combined life that doesn’t obliterate the two but enhances the growth of each.

Then at some point, or points, come the inevitable cracks in the created work: dissonances, tensions, the sonnet form breaking down into chopped-off lines and loss of rhyming.

It took George and me a couple years of therapy to get our rhyming back after our marriage’s worst breakdown several years ago. With professional help and lots of restoration work, we began the re-creation of our joint life.

My favorite images for the work of art that is married love come from Richard Wilbur’s poem to his wife: “For C,” in his 2000 collection Mayflies. He had been married to Charlotte for nearly five decades when he wrote this poem in his late seventies.

The poem’s opening three stanzas evoke in delightful, crisp images some tumultuous love affairs that the poet witnesses from afar—like “this other pair whose high romance / Had only the duration of a dance.” Then for the closing two verses, he turns to address his wife:

We are denied, my love, their fine tristesse

And bittersweet regrets, and cannot share

The frequent vistas of their large despair,

Where love and all are swept to nothingness;

The denied of this first line suggests playfully that the poet and his wife are missing out on something in life, since they cannot share the torrid dramas of tumultuous love. But the stanza continues:

Still, there’s a certain scope in that long love

Which constant spirits are the keepers of,

“Still”: the word hints at the cautious offering of a different sort of love, which gets elaborated in the astonishing single sentence that runs until the poem’s end:

Still, there’s a certain scope in that long love

Which constant spirits are the keepers of,

And which, though taken to be tame and staid,

Is a wild sostenuto of the heart,

A passion joined to courtesy and art

Which has the quality of something made,

Like a good fiddle, like the rose’s scent,

Like a rose window or the firmament.

The crescendo of these eight lines is slow but steady. They begin softly, in a tone of: well, still, maybe there’s something good about that long love. There’s, for a start, a certain scope—the long view that long life together affords. But long love requires constant keeping; it is always a work-in-progress.

The first line of the closing stanza stays quiet: this long love appears perhaps tame and staid. Then the slow crescendo begins, along with explicit images of art. The work-in-progress that is long love is, first, a sostenuto: a phrase of music, a sustained passage, sustained for a lifetime. Yet, in a wonderful oxymoron, this sostenuto is wild. Long love sustains a wildness of the heart.

The next line, increasing the crescendo into passion, also seems oxymoronic. Passion is wild, dramatic; yet the passion of long love is joined to courtesy—to manners of respect and insight that anticipate the loved one’s needs. That and joining courtesy and art presents art, too, as something care-fully made.

And, indeed, that’s exactly where the next line goes: this courteous, art-full passion has the quality of something made.

And then comes the crescendo of the poem’s final couplet, four similes for the something made that is long love:

Like a good fiddle, like the rose’s scent,

Like a rose window or the firmament.

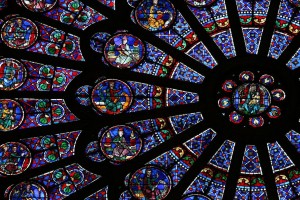

First the human artistry of a good fiddle, then nature’s artistry in the rose’s scent. Then—quite a sweeping crescendo here—nature’s rose taken up as the work of human hands into the rose window characteristic of medieval cathedrals.

Here we stand under the vault of a magnificent Gothic church, gazing at the grandeur of the rose window. Gazing at the penultimate image of long love.

Then the ultimate, consummate image lifts our gaze even further, as the crescendo reaches its climax: long love is like the firmament. And since all these images are of something made, we ask “who or what is the creator of the firmament?”

Maybe just nature, if we see the firmament simply as the dome of the sky. But for religious believers like Wilbur, firmament evokes heaven, the place God makes for our eternal joy.

Suddenly long love is as far from tame and staid as possible; it is God’s own work.

In my (Catholic) faith, marriage is a sacrament: a making of the sacred. It is the ongoing joint creation of the spouses and God. For which we give thanks, daily.