At the end of December I talked to a friend of mine who lives in Seattle. He was going to a New Year’s Eve dinner and was having trouble deciding what to contribute to the meal. “It’s strange,” he said, “that Americans don’t have any traditional New Year’s foods. We have Thanksgiving food, and Christmas, but not New Year’s.”

At the end of December I talked to a friend of mine who lives in Seattle. He was going to a New Year’s Eve dinner and was having trouble deciding what to contribute to the meal. “It’s strange,” he said, “that Americans don’t have any traditional New Year’s foods. We have Thanksgiving food, and Christmas, but not New Year’s.”

What I found strange was that he’d grown up without a food tradition on this holiday, because my family always ate black-eyed peas, greens, and cornbread on the first of January, and although I knew it had originated in the South, I’d thought the tradition was now widely known, if not widely practiced.

Each year my parents, brother and sister, aunts, uncles, cousins, and I would gather in my grandmother’s kitchen.

“The black-eyed peas are coin money,” Grandma told me, stirring the big, black pot where the beans floated in a bubbling liquid, a smoky chunk of fatback bobbing in the middle like a buoy.

“But the greens are paper money,” she said, “so that’s what you want to eat the most of!”

While collards and mustard will do (some even substitute cabbage or kraut), Grandma made turnip greens. She cut them into small pieces and boiled them with chopped onion and lots of salt, then served them sprinkled with sugar or vinegar. I’d eat two bowlfuls of greens in potlikker—their savory liquid—and was proud when she said she’d never seen a little girl as good at eating greens as I was.

While some prepare rice to accompany the black-eyed peas (Hoppin’ John), families I knew served cornbread as the starch, baking the aromatic yellow discs in cast-iron skillets greased with lard or shortening. The golden color of the cornbread signified further luck or riches in the new year.

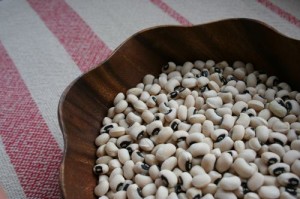

Eating greens or cornbread alone, however, wasn’t enough to ensure good fortune. The magic key—and center of the meal—is black-eyed peas, which came to signify prosperity because of how they swell as they cook.

Black-eyed peas aren’t really peas at all; they’re legumes, and a subspecies of the cowpea. Transported to the low country coastal regions of America (in Georgia and the Carolinas) by African slaves, they were at first considered a lowly food, fit to feed only slave families and livestock.

During the Civil War, however, after Sherman’s troops stripped fields of their crops but neglected the black-eyed pea plants, the beans became an important source of nutrition, and earned a permanent spot in the Southern culinary repertoire.

Some believe the tradition of eating black-eyed peas on the first day of the year began this way, while others think it originated with Sephardi Jews who settled in Georgia early in the eighteenth century and considered black-eyed peas (along with some other foods) symbols of good luck, to be eaten at Rosh Hashanah. If that tradition carried over to non-Jews, it also happened around the time of the Civil War.

Either way, it seems unlikely that black-eyed peas would, all this time later, symbolize our hopes for a prosperous year. As far as beans go, they aren’t the handsomest specimens—neither large like the red kidney, nor glossy like the black, nor mottled like the pinto. They are small and white, with a black spot in the middle reminiscent of a pupil (hence the name). When cooked, they look even more unappetizing. They turn gray, shed their delicate outer casings, and muddy the boiling water.

However (and I realize not all are in agreement on this point), the final product is delicious. The beans are soft and creamy, with a nutty, buttery flavor. While excellent cooked with pork, and divine topped with chow chow (a spicy pickled cabbage relish), water and salt are all one needs to turn the dried beans, which don’t need to be pre-soaked like most others, into an appetizing dish.

This year I made my own black-eyed peas, collard greens, and cornbread, and ate them happily with my husband and roommate as we talked through our hopes for the upcoming year. After the extravagance of Christmas—its rich gingerbread and frothy eggnog, its crispy roasted meats, sugared fruits, and frosted cookies—enjoying a simple meal felt right.

The humble foods symbolized not only our desire for health, luck, and prosperity in 2013, but also our humility in the face of the unknown. Who knows what will happen in the future? Not one of us. But we can face the unknown like these small beans in our bowls, each a separate eye gazing out, unblinking.