A Guest Post by Daniel Siedell

A Guest Post by Daniel Siedell

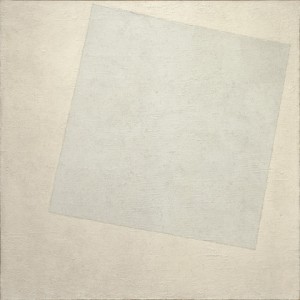

My approach to abstract painting changed forever fifteen years ago during a conversation with an artist friend in front of Kasimir Malevich’s White on White (1918) at the Museum of Modern Art.

As I was telling my friend about Malevich’s theories of abstraction and his utopian belief that paintings of squares and rectangles could transform society, my friend interrupted me and, with his nose about as close as one could get to a painting, whispered, “Look at this surface! How did he do it?”

As I looked at that meticulously worked-over canvas, White on White became something other than an idea or a theory.

It became a painting—a vulnerable, futile, and weak object, lovingly and painstakingly made by a human being in the midst of a world turned upside down by World War I and the Russian Revolution.

All of a sudden, Malevich’s rhetoric about the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts” and his desire to “free art from the ballast of the objective world” faded away, and I was confronted with one thing:

In the midst of chaos and exhilaration, of hope for a new world and a new humanity, Malevich painted a picture of a white rectangle on a white ground. What a wonderfully absurd thing to make.

Walking through the galleries of Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925 at the Museum of Modern Art several weeks ago, every work on view appeared to me wonderfully absurd, delightfully contradictory—and therefore, extremely dangerous.

The goal of abstract painting is simple but radical. Free a picture from the need to represent the world—real or imagined—and use line, color, and form alone to produce an emotion or feeling. These artists rendered their work even more useless and marginal than other paintings by refusing to represent the things of this world with which we already have relationships, such as persons, bouquets, and landscapes.

And so the artists experienced resistance from the media and the public.

Artists like Malevich felt obliged to defend themselves, to strengthen their absurd paintings through words. So they wrote about purity and directness of experience. But their writings, which theorized, pontificated, and thundered about transformation and a new world, testified against their fragile pictures and simply affirmed the absurdity of their drawings and paintings of line, colors, and forms.

It is not surprising that these pictures became targets and the artists who painted them considered dangerous by governments fearful of the freedom to do absurdly wonderful things like paint pictures that had no apparent use.

Inventing Abstraction also pays homage to an unlikely hero, a vulnerable and frail man in his own right who just might have been responsible for saving many of these contradictions in paint, and even the persons who painted them.

In 1933, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., after four years on the job as founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, was granted a year’s leave of absence for nervous exhaustion. Barr and his wife spent the year in Germany and Barr was horrified by what he saw. Hitler had been named Chancellor of Germany that year and the Nazi party had begun targeting abstract paintings (and their makers) as degenerate.

Barr wasn’t concerned with the artists’ writings, their ideas and theories. He worried about the paintings themselves and the fate of their makers, many of whom were already in hiding or making plans to flee Germany.

And so this somewhat pedantic and obviously nervous scholar embarked on a courageous course of action. He began to find ways to save the artists and their art by bringing them to New York. In addition to buying work directly from the artists and dealers, he conceived of an exhibition shortly after his return that would serve as cover for his rescue mission.

Through the exhibition he was able to arrange for loans, which he planned to turn into purchases. Through his work, New York became safe for abstract painting, safe for the embattled artists who painted them.

Barr’s groundbreaking exhibition, entitled Cubism and Abstract Art, opened at the Museum of Modern Art in 1936, just one year before Hitler’s notorious Degenerate Art exhibition. The exhibition was Barr’s protest against fascism and a celebration of human freedom embodied in those lines, colors, and forms.

Inventing Abstraction bears witness to the reality that artists, like Malevich, had hoped that their artistic artifacts would change the world and transform humanity. The artists were right to believe that their work was subversive. But in the end, they needed protection from the very people they hoped would be changed by them.

What is the contradiction of abstraction to which Inventing Abstraction bears witness?

I’ll let the curator Leah Dickinson answer that question: “Abstraction’s pioneers announced its arrival with great fanfare, using the language of purgation, dissolution, and repudiation. But it only became fully institutionalized as a project of rescue, retrieval, and preservation” (my emphasis).

Mark Rothko, one of the most famous abstract painters in the United States, himself a Russian immigrant, was right. It is a risky business to send a painting out into the world.

Thank God for Malevich who had the courage to send White on White out into the world, which, on a dreary winter day many years ago, taught me to see even the most difficult and empty paintings to be full of humanity, suffering, and love.

And thank God for Alfred H. Barr, Jr. who loved abstract painting enough to bring White on White and so many others to New York, for you and for me.

Daniel A. Siedell (M.A. SUNY-Stony Brook, Ph.D. Iowa) is on staff at Coral Ridge Presbyterian Church in Fort Lauderdale where he is curator of Liberate, the resource ministry of Tullian Tchividjian. He is the author of God in the Gallery (Baker Academic, 2008) and numerous writings on Christianity and modern art. He blogs weekly at Cultivare.