In his great work, Earthly Powers, Anthony Burgess has the main character—Kenneth Toomey, a doddering, debauched, eighty year-old novelist—remark upon the insignificance of his life’s quest, the search for the “right” words:

In his great work, Earthly Powers, Anthony Burgess has the main character—Kenneth Toomey, a doddering, debauched, eighty year-old novelist—remark upon the insignificance of his life’s quest, the search for the “right” words:

I was thinking like an author, not like a human, though senile, being. As though conquering language mattered. As if, in the end, there were anything more important than clichés.

Toomey goes on to contemplate the word “faithful,” one of those old all-encompassing terms that celebrated writers have labored their whole lives to come up with an objective correlative for. Still, the mere thought of the hackneyed concept nearly brings the decrepit novelist to tears:

“You have failed to be faithful” he thinks, lapsed as he is, fallen as he has become. It is the lines of the passé Christmas chestnut that fill his eyes to the brim:

O Come All Ye Faithful.

Weary and at the end of his life, this truth about clichés discloses itself to him like something come upon in the pocket of a childhood coat—a thing put away in one’s youth, forgotten, recovered by sheer circumstance. It is the kind of revelation that brings down the castles built over a lifetime.

“All is straw,” said Thomas Aquinas, of the million words he had written when compared to the vision he was granted of his Lord.

Despite their pejorative connotation, it is the clichés that we hold in our heads (more in our hearts) the longest—fundamental notions in their simplest, commonest expression. We recognize them immediately, grasp them atavistically.

Is this what is meant by the counsel to “see as children see”? A widespread misinterpretation of the axiom is that it means to “fathom as children fathom,” to understand as they understand. But that cannot be the case.

The depth of the mature mind is obviously superior to that of the unformed, regardless of our preposterous age’s quixotic notions about infancy.

No, what must be meant is that a child sees the things that are most important—the outlines of the particular face that are so dear and crucial, the exact comforts that truly warm, the precise joys that bring satisfaction, peace.

A child is not distracted by a price tag as we are, or by the illusions of grand association. He may play with a prince, but that his playmate is a prince is not why he plays with him.

And so it may be with words and the concepts that they encapsulate. We come to find that the most basic are all that remain consequential; other simplicities are likewise appreciated at last, not at first—and even so, only if brutal honesty about them is admitted.

Stereotypes (in French, les clichés)—again, for all their negative undertones, would not be stereotypes were they ungrounded in lived experience; archetypes—more respectable—would not stand as they do were they not so key, the under-bones and crude (but who am I to call them crude?) network of elementary contacts that tapestry our brains like cave etchings from Lascaux.

True, these things are not the stuff of art. We love our conceits, are transported by them. The best are collected like sculpture made of glass. Some of my favorites:

“He looks like right after the maul hits the steer and it no longer alive and don’t yet know that it is dead.” (William Faulkner: As I Lay Dying)

“The swamp was now all-enveloping, dark and at the same time vivid, alarming—it was like being inside the chest of something that breathed and might turn over.” (Eudora Welty: “Moon Lake”)

“Let us go then, you and I; When the evening is spread out against the sky; Like a patient etherised upon a table.” (T.S. Eliot: “The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock”)

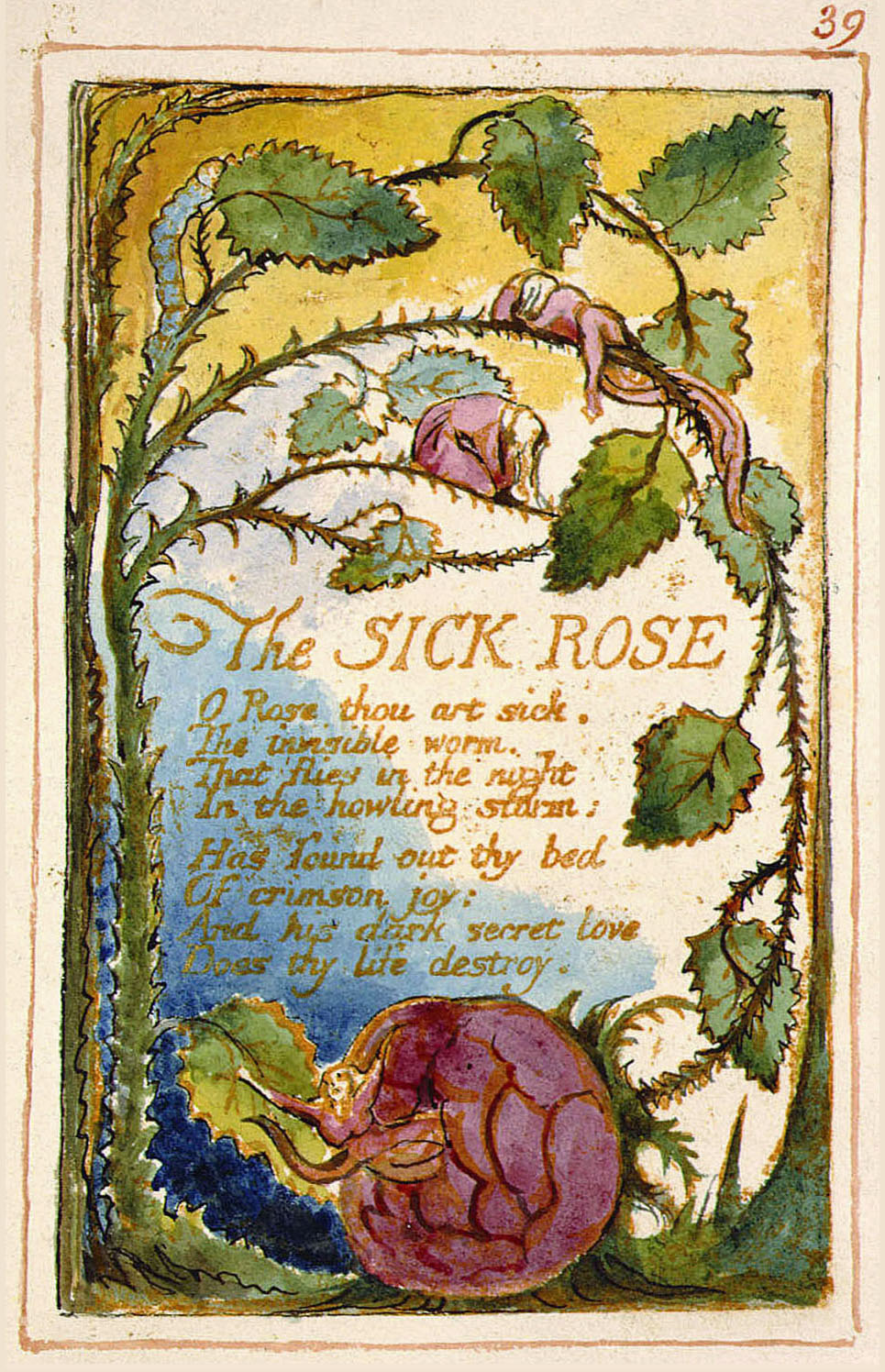

“Oh Rose, Thou art sick. The invisible worm, That flies in the night / In the howling storm: Has found out thy bed / Of crimson joy: And his dark secret love / Does thy life destroy.” (William Blake: “The Sick Rose”)

Ah, yes. That is the way of art, we must admit. We strive for novelty like this—to make things new, to create fresh angles. Soaring similes, spearheaded with “like” and “as”—metaphors, barn-solid or diamond-pure; they will always be the Shangri-La of the word-smitten. It has a decided vanity to it all, this business: playing God in the Garden of the Dictionary.

And maybe that’s the only way to make art. As Browning said, “A man’s reach must exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” Nevertheless, it is heaven that is our purpose, not the making, doing, toiling.

Our loveliest paths are but shimmering ways back to the thing in that old coat pocket. The pursuit is fine—good—necessary, even. But maybe the great wide world and every means of transport through it is just a roundabout way of learning a lesson: that it is the end of the trip—the finding, not the seeking—that we want.

For all our airy flights—our great darlings—paragraph and page, stanza and couplet—we are really only talking about the clichés, the melodrama of crayon scrawls that first made our world for us—mother, father, help, love—and at last, when we become children again, “ragged coats upon sticks,” that make the only world available to us anymore.

We spend our youth and adulthood rolling our eyes at things that I suspect, in the end, are the only things we want to roll our eyes toward.

“I go to seek a Great Perhaps,” said Rabelais, at his last.

And what a fine line that is, uttered by a true artist. How clever, how apt, how arch.

But still and all, I’ll bet that underneath such a gallant, witty bon mot, giving it meaning and purpose, was that old cliché for which he searched, longed, hoped: that robed, white-maned gentleman, august and eternal—“Smiling like a Sun.” Alpha. Omega. Beginning. End.